Like most technological innovations, multispectral photography is politically neutral in and of itself. It means that the camera can reveal generally invisible parts of the colour spectrum such as infrared and ultraviolet, whilst also allow- ing them to isolate and enhance single tones such as blues, greens and reds. This technique has been employed to map earth’s vegetation and coastlines from outer space with new levels of detail, but it has also been used by military forces around the world to track and kill human beings.

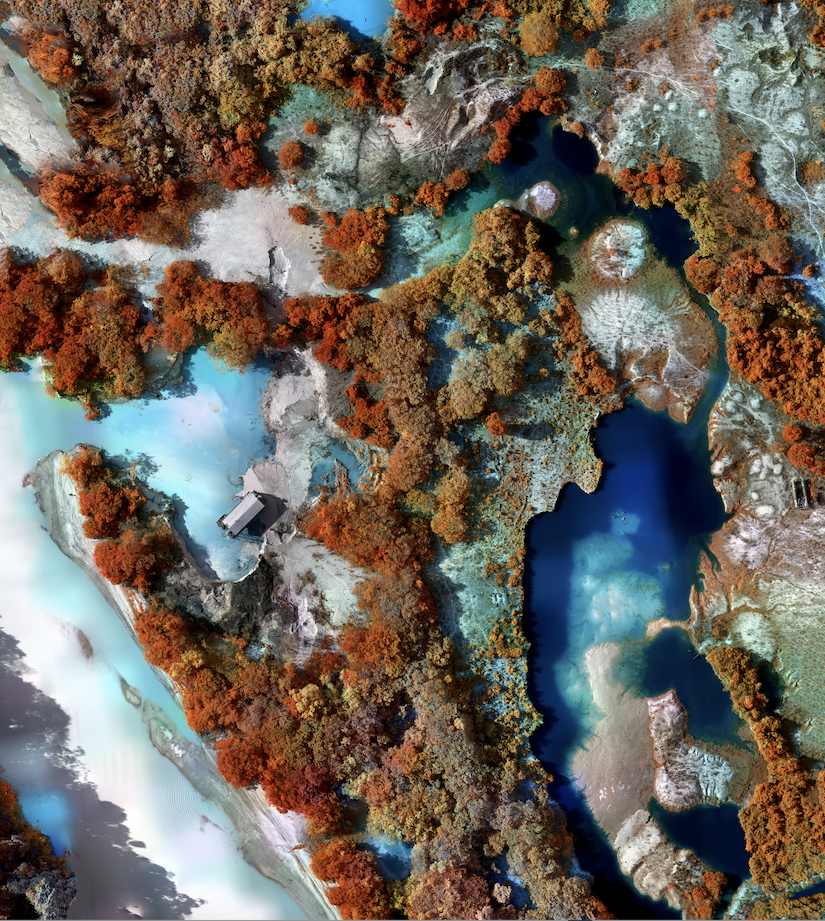

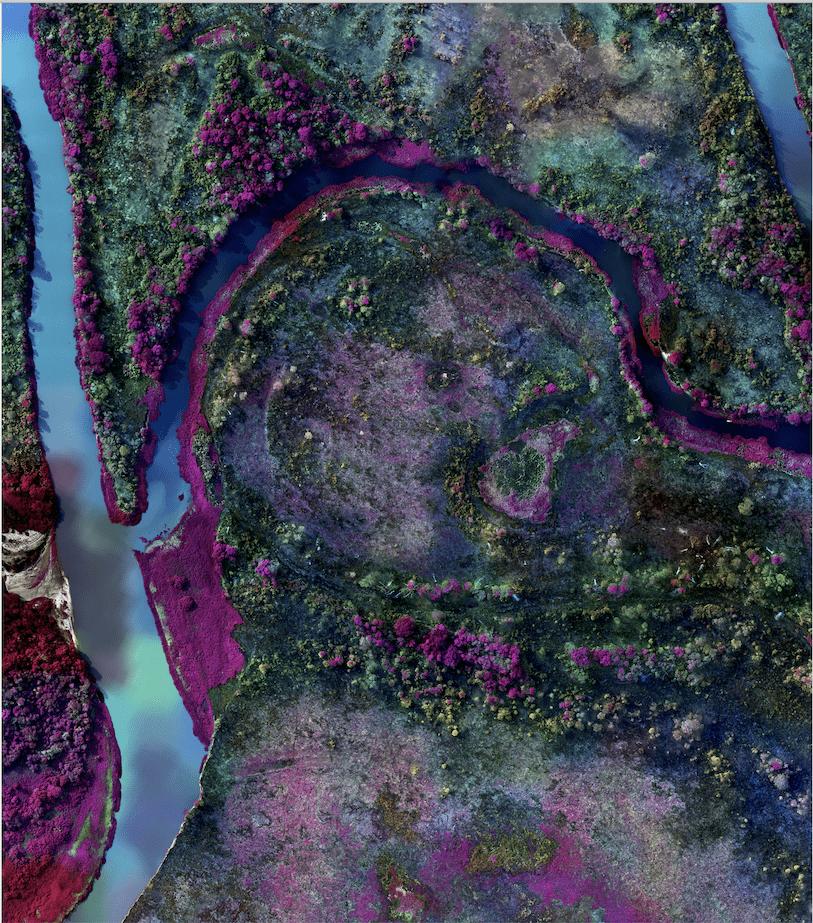

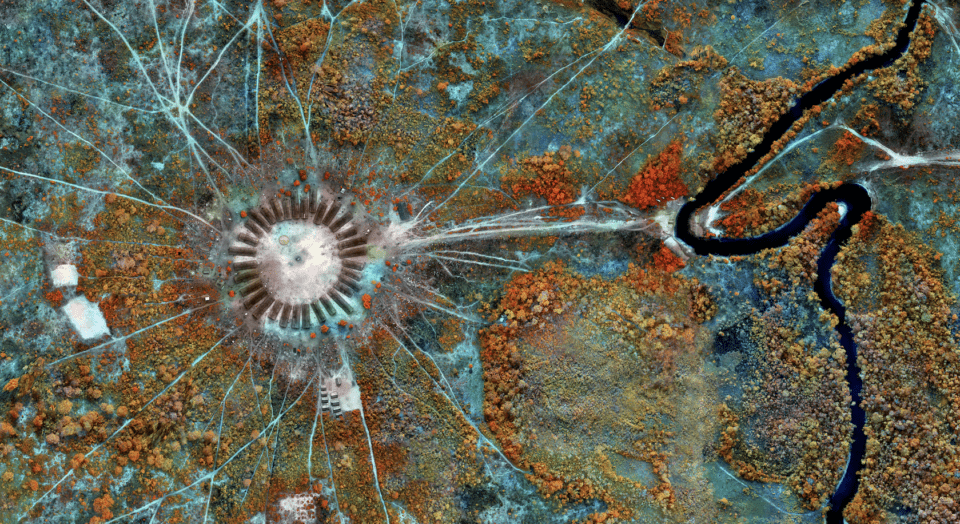

The application of multispectral photography in the Amazon presents a more specific moral conflict. Environmentalists harness the unique optics of the form to trace the destruction caused through deforestation and mining, but the very agribusinesses and mining mineralogists causing harm can use the same devices to identify new sites for burning and digging. Richard Mosse’s (b. 1980) Tristes Tropiques series, created by flying photographic drones across Brazil’s so- called “arc of fire,” uses enhanced colour spectra not just to draw attention to a ravaged ecosystem, but also to suggest the conflicted roles of science and cartography in both preserving and overrunning the natural world.

Mosse is an Irish artist whose work has long harnessed the photographic medium in bold news ways. He forces viewers to look again at images of catastrophe, counteracting the numbing effects of constant news cycles and social media posts, making us confront these subjects as if for the first time. Early in his career, he travelled to conflict zones from Kosovo to Iraq, documenting the human aftermath of war and violence, situations in which habitual human behaviour somehow seem unreal. One extraordinary 2009 shot shows a group of US soldiers around a rubble-filled swimming pool in the bombed-out palace of Saddam Hussein’s son (Ruined swimming pool at Uday’s Palace, Jebel Makhoul, Iraq).

For the breakthrough Infra (2012) series, however, Mosse turned to a more formally adventurous means of estrange- ment. The subject was Kivu in DR Congo, a mineral-rich region shattered by successive waves of violence stretching back decades, most recently fomented by rebel militias in flight from the Rwandan Civil War of 1990-1994. The artist travelled the area with an obsolete military reconnaissance camera that picked up infrared light – much of it absorbed and reflected by plants – transforming the lush Congolese undergrowth into a surreal dreamscape of magenta and crimson. The project brought an arresting backdrop to an ongoing scene of human devastation, thereby forcing view- ers to sit up and notice. The accompanying audio-visual work The Enclave (2012) used the same infrared camera to depict rebel soldiers training against the tall grasses and foliage, their gestures and expressions becoming simultaneously more aggressive and more theatrical as the shoot progressed.

“When you’ve seen this work, you’ll never forget the Congo,” says Urs Stahel, the curator of Displaced, a major mid-career retrospective running at the Fondazione MAST, Bologna. The principle of “making new” – which ultimately powers Mosse’s creativity – also applies to the more recent series Heat Maps and Incoming (both 2017) in which heat-sensitive imaging re- veals the movement of human bodies across refugee camps in Europe and the Middle East as a ghostly silvery mass.

Over the last few years, however, Mosse has focused on what he calls “environmental crime,” and to a technology discovered, according to a recent interview with The Monocle, after pondering how to adequately depict the effects of human activities in the Amazon. Faced with “the extensive media blitz coverage of burning rainforest” during summer 2019, the artist became “intrigued by the challenge of representing climate change and environmental catastrophe. Because it’s just so bloody difficult. It’s outside the limits of human perception, the limits of language. It’s way bigger than us. And for that reason, it’s very difficult to photograph.”

Mosse often speaks of art in terms reminiscent of Irish author Samuel Beckett (1906-1989): as a process of coming to terms with a failure of expression. However, a solution of sorts came when he began to research the photography used in environmental monitoring satellites, which move across the earth at high speed recording its topology. The enhanced reds, greens and blues of the different visual “bandwidths,” as well as the invisible spectra of UV and infrared, are used to record processes such as the release of carbon dioxide.

At the same time, Mosse recalls, “some of the maps they were producing were very aesthetically powerful.” This was the spur to the still-evolving set of images known as Tristes Tropiques. The title references a memoir by French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908-2009) which recorded his travels throughout Brazil – a nod to the historically complex interaction of western intellectuals with indigenous communities who inhabit many of the areas now at risk from fire and felling. As Stahel explains, drones were flown in rectangular grid patterns across vast swaths of the Brazilian interior, generating sets of pictures which were then stitched together to create a form of “counter-mapping:” “not mapping to use the world, but to make people aware how we are misusing it.”

These compositions captivate audiences with beauty but then, almost immediately, make us question the terms of our enchantment. Copper-orange canopies give way to textured white plains. Bright pink riverbanks articulate the fringes of deep opalescent masses, where blues, greens and greys in- termingle as if in intergalactic space. These are compositions which truly “estrange” – allowing a process of imaginative re- acquaintance with subject-matter. At the same time, viewers are left wondering what it means to encounter an image of planetary destruction as sublime, awe-inspiring even. For the colour palettes which convey these moods are also models of disorder: they record the deliberate blazes caused by cattle ranchers clearing space for their herds; the release of poisonous mercury into rivers through the detonations and extraction of gold miners; the steady seep of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere at points of concentrated release.

“Lots of younger artists say we have to renew the images of climate change,” Stahel notes, “and I always think we should immediately tell them: look at Richard Mosse!” As the curator suggests, Mosse is not the only photographer or multi-media creative working to shed new light on the threats posed by and towards humanity – and those who also inhabit the planet. For example, Mishka Henner’s (b. 1976) Feedlots is a profoundly bleak set of satellite photographs showing huge, gridded feeding pens on arid land in Texas, flanked by luminous cesspools of animal waste mingling with polluting chemicals. The scale and formal allure of these images is such that viewers are forced to scrutinise them closely to realise what they are seeing: that the black dots peppering the landscape are living beings, a multitude of farmed cattle. Intermedia artists such as Michael Wang (b. 1981) have taken a different tack, using three-dimensional forms and live installation to reacquaint audiences with what they already know, but don’t want to feel, about their relationship with the planet. Wang’s 2017 exhibition Extinct in the Wild, at the Fondazione Prada, Milan, brought together a range of flora and fauna exclusively preserved in cultivation or captivity. Wang’s installation, which presented species no longer found in nature with clinical, lab-style lighting and décor, highlighted the extent to which human “progress” has reduced the organic world to a passive object of study, whilst industry and commerce have made a desert of the wildness beyond. By contrast, practitioners such as Daisy Ginsberg (b. 1982) have used imaginative mapping, architectural drawing and VR modelling to propose ways in which nature might evolve to survive the onslaught caused by the human race.

These individuals – and, indeed, many others – use new creative and technical approaches to freshen the visual and sensory languages employed to communicate the climate emergency to a wider audience. What sets Mosse’s work apart, undoubtedly, is its beauty, and the way in which these arresting aesthetics confront how we perceive and consume the essence of catastrophe. In a society of pervasive adver- tising and media spectacle, perhaps only stunning techni- colour could rouse us from apathy, much as Andy Warhol’s neon silkscreens of car wreckages reflected back the appetite for glamourised tragedy. In lacing transcendent images with this stinging message, the artist of climate disaster also be- comes an artist of – and against – photography.

All of this nudges us towards a debate initiated by Susan Sontag’s 1977 book On Photography, which continues to bubble within the pictorial community and culture at large. In short, can photographs ever do more than offer a distract- ing or mystifying spectacle? Can they motivate us to act for positive change on a topic such as ecological destruction? Whilst Sontag’s position was that they cannot – at least not on their own – a new generation of critics has guardedly revised such perspectives. Meanwhile, images circulating across the globe for the last half-century – from a self- immolating Vietnamese monk (Malcolm Browne, 1963) to a naked child burned with napalm (Nick Ut, 1972) to horrify- ing shots of tortured inmates at Abu Ghraib during the Iraq War – have become talismans for political opposition to the atrocities committed by western governments.

The question of whether or not photography can change the world – or prompt us to change it – is as difficult to answer as the broader question of art’s social value. However, the allure of Mosse’s work is not merely a way of prompt- ing self-critique on the way we engage with climate chaos or genocide. By contrast, the artist is emotionally entwined with the communities and landscapes he documents, and wants the dazzle of the image to serve as a spur to reflection, and ideally action. “He is interested in the context of the conflict, whether in society or nature,” Stahel explains. “He is not the kind of photographer who gets paid to go somewhere for two weeks and leaves. He goes back for years. He went to the DR Congo for five years, and knew the people, going back in order to show them the photographs. It was a conscious deci- sion to work like this, and he is doing it in Brazil too. But still,” Stahel concludes, “Mosse believes in the visual power of the image.” It is beauty, it seems, that will change the world.

Displaced: Richard Mosse is at Fondazione MAST, Bolonga Until 19 September. mast.org

Words: Greg Thomas

Image Credits:

1. Burnt Pantanal II, Tristes Tropiques. © Richard Mosse. Images courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery and carlier | gebauer.

2. Mineral Ship, Crepori River, State of Para, Brazil, 2020. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid.

3. Felled Brazil Nut Tree, Tristes Tropiques. © Richard Mosse. Images courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery and carlier | gebauer.

4. Burnt Pantanal I, Tristes Tropiques. © Richard Mosse. Images courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery and carlier | gebauer.

5. Gold Pit, Paraprint, Tristes Tropiques. © Richard Mosse. Images courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery and carlier | gebauer.