For as long as humans have created artworks, they have created images depicting nude figures. They are everywhere – from marble antiquities to modern painting. Contemporary artist Mona Kuhn (b.1969) brings her own sensibility to photographing unclothed bodies. Through Kuhn’s lens, nudity becomes an egalitarian force, a form of spiritual kinship. As Mona Kuhn: Works, a retrospective book of her work over the past 20 years is published by Thames & Hudson, Kuhn talks about how she came to focus on nude portraiture and the role that nature plays in her work.

A: You’ve been taking photographs since you were 12 years old. What drew you to photographic portraiture, and capturing nude figures, in particular?

MK: My parents are German – they moved to Brazil in 1967 for my father’s work and I was born in 1969. I loved growing up in Sao Paulo, there were immigrants from all over. I had Japanese friends, Lebanese, Hungarian, Polish, British. It was a bit of a utopia. My mother was very social, she was always out and about with her girlfriends. I got bored of all the talk so when I was a teenager, when she’d meet with friends I’d ask her to drop me off at the Museum of Modern Art. In the 1980s, the museum was empty and very calm. I loved it. I’d sit for hours on the benches just staring at the artworks: European, American and Latin American. I was looking for paintings that gave me a feeling of connection, of transcendence, and these were mostly figurative.

I got into photography when I was studying fine art. The medium suited the spontaneous kind of person that I am. I’d get impatient making paintings, they take so long. I also always thought that sculpture is really interesting but the physicality of it felt beyond what I could handle and the materials are so expensive. I consider myself 100% to be a photographer but I want to carry the vocabulary of all the arts into photography. When I was starting out, photography was being more used as a record or a document. I thought, why can’t we bring Impressionism into photography? How would we smear the paint in photography? Or how would we abstract a little further?

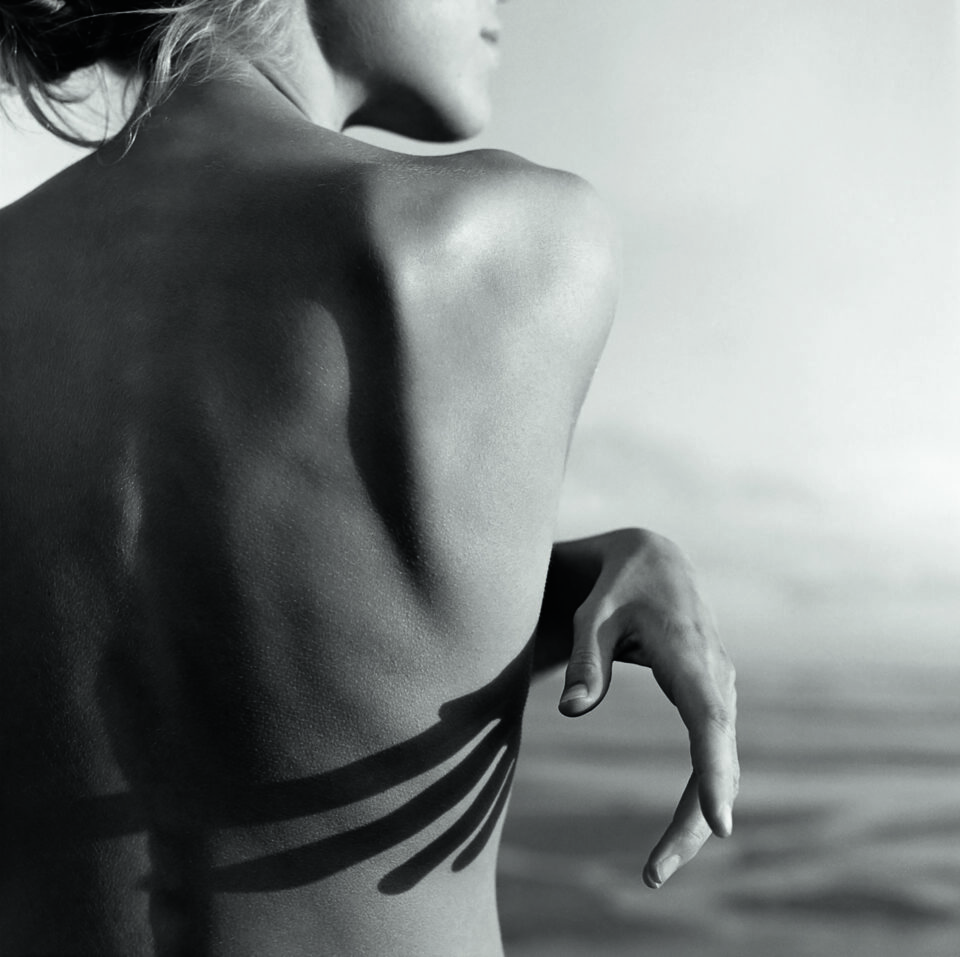

Even though I was in love with photography at college, I found it was a very fast medium and I somehow wanted to slow it down. That’s the moment when I thought, you know, maybe I can stop time by trying to figure out how you can bring the nude into photography in a way that’s timeless. This was the early 1990s. The big names were people like Helmut Newton or Herb Ritts; the full figure was sharp and very descriptive. I thought, what about the metaphors? I wanted to bring my vocabulary to the body in photography. I started with black-and-white with details, gestures and metaphors.

A: Would an example of that early work be, say, the image where you can see two figures, almost in silhouette, with their hands side by side?

MK: Right. In a way, that image is not so much about those two people, that image could be you and I. To me, what was more important is that the arms fall in parallel. They are together but not leaning on each other. They are in balance. Beyond the nudity, the body is a platform for emotions, for metaphors and for expression. At the beginning I was a little scared because the nude has been done before.

A: The nude certainly comes with a long art historical lineage. How have you reacted to this within your own work? Who are your artistic influences?

MK: I really like Joseph Stieglitz’s nude photographs of Georgia O’Keeffe. One of my early influences in photography was a Brazilian photographer called Mario Cravo Neto, who worked in the northeast part of Brazil. Stieglitz’s photographs of O’Keeffe are really about his love for her more than the fact that she’s nude. I could still feel the caring energy between those two because they were lovers for some time. And I could tell that they were creating something beautiful together. That was similar to the energy I experienced looking at certain paintings in the Museum of Modern Art.

There is something about the nude that offers a more elemental, maybe more egalitarian, presence. We’re stripped of our status symbols, the things that create a hierarchy, and it’s a little bit more about collaboration. I realised that I didn’t want to make the nude images that I was seeing, shot in studios or fashion style nudes. I wanted to be in a place where art and life come together. I’ve always loved the work of Lucian Freud because it has this calmness and quiet.

A: How did you go about starting to photograph nudes? Who were your first subjects?

MK: I felt awkward asking people to pose nude at first. I realised that I needed to go to a place where people had a different mindset. In the mid 1990s a friend told me about this community in France on the Atlantic coast. It’s a very remote conservation area, very empty. In the 1950s, following socialist egalitarian principles, some French families had built a little community of identical bungalows. Their philosophy was about embracing nudity as a way to find commonality between people again after the traumas of the Second World War. That was now four generations ago, and some of those grandparents are still around. I fell in love with this place. It’s very family-oriented, there’s no internet, you’re off the grid in nature, and you kind of want to abandon yourself.

The first year I went there I didn’t take any photographs. You’re allowed to take photographs with your friends but people are there to relax, they don’t want a photographer showing up. The second year I brought my camera and started to photograph myself using a long shutter cable. I don’t like self-portraiture but I wanted to do something. Then a young woman came over and asked me what I was doing. I explained that I was a photographer. She started helping me with the framing. Eventually she offered to step in so I could photograph her. That’s how it began. I returned every year, taking photographs of different people, bringing back prints from the previous year to show them. It was a dream come true.

A: Those earlier images are very much focused on bodies and gestures. In later series such as Native, you bring more of the environment into your nudes, sometimes interspersing portraits with images of lush foliage. What’s the role of nature for your work?

MK: I think we’ve realised, especially in the past year, that nature has a recharging power. I grew up in a big city, Sao Paolo, and I now live in LA. I’m a city girl! But I do see the grounding impact of nature. It’s humbling, you understand you’re part of a bigger force and you need to find your balance within that. To shoot Native, I went back to Brazil. I wanted to photograph my native country, the country where I was born and raised. And I remember when I got out of the plane, it just hit me: the tropical heat, the sounds, the smells – and the nature. You have these enormous rubber trees breaking apart sidewalks in the middle of the city. Nature’s so strong, so powerful there that it had to be an element, almost a character, in the series. So I went to photograph in the rainforest. It was such a beautiful cathedral-like place, very high tree tops, green all around you, and dappled light coming in from the centre. The sound is so calming. You can hear hundreds of birds, also insects. But the first pictures I shot were terrible. They looked really flat and didn’t capture the grandiose feeling of the environment. I realised that you can’t capture the whole of that in the camera frame so instead I used selective focus to highlight small details of vines or openings in the leaves in a more careful, more caring way.

A: There’s a tactile quality, a sense of togetherness, in your work, which feels particularly pronounced after the recent experience of living through the pandemic and social distancing. How has this time been for you? What impact has it had on your practice?

MK: In 2020 I didn’t photograph at all. It felt as if my soul was being distorted. Doing my creative work really balances me. It’s who I am, how I understand my identity, my contribution. A whole year without photographing people made me feel really detached from myself. In LA I live in the canyon area where there are oak trees some hundreds of years old. I’ve been photographing the way the vegetation has been changing with the seasons, treating my back garden, which is a 45 degree hillside as a tableau trying to bring metaphors out by focusing on the details – a minuscule sliver of light coming out of the darkness.

A: What are you working on next?

MK: Just before the pandemic, I had finished a series of 30 images of one man. It goes through the whole emotional range of that person. That’s something I hadn’t done before. It was a challenge. How do you photograph a man nowadays? There has been so much turbulence about how to define a man, it’s no longer the Marlboro Man. And I wanted to have my own interpretation.

For every series that I do, there is a little seed that transports me into the next one. The series She disappeared into complete silence was about refractions. Our minds are in multiple places. We live in a physical slash digital reality. The reflective surfaces were to me an extension of my own camera, which has the lens and the mirror inside. It was a real creative collaboration with the model Jacintha, who has studied art history, working together to explore how else to refract her presence and push into abstraction. This is the most abstracted I have taken the figure through the human, the landscape, the structure, the light. But the seed that took me into the next series was the thought: what if I could take this further and have the figure cross the element of time? I can’t say any more than this! But it will be out next year…

Find out more here.

Words: Rachel Segal Hamilton

Image Credits:

1 & 6. © 2021 Mona Kuhn. AD 6046, 2014

2. © 2021 Mona Kuhn. Phillip II, 1997

3. © 2021 Mona Kuhn. Succulents 6, 2018

4. © 2021 Mona Kuhn. AD 6387, 2014

5. © 2021 Mona Kuhn. Sombra, 1999