In 1963, a trailblazing collective of Black photographers – the Kamoinge Workshop – was founded in New York City. The name came from the language of the Kikuyu people of Kenya, who gained independence from colonial rule in the same year. “Kamoinge” translates as “a group of people acting together – a principle that guided founding members Earl James, James Ray Francis, Louis Draper and Roy DeCarava. The group cultivated a supportive environment for Black image-makers to authentically document African American experiences during the Civil Rights movement and beyond. Ten years later, Ming Smith (b. 1950) became the first women to join the collective.

The Detroit-born photographer is now the subject of Projects: Ming Smith at MoMA, a major retrospective that offers a “critical reintroduction” to her practice. Early photographs document neighbourhoods that she encountered after moving to New York. In Mother and Child, Harlem, NY (1976), the pair stand by a phone box, the mother’s cheek daubed silver beneath a streetlamp. Elsewhere, a catalogue of images records famous landmarks, urban environments and Black cultural icons. The artist’s wide-ranging, experimental body of work captures fleeting experiences within the mundanity of everyday life – all shot in her signature black-and-white street style.

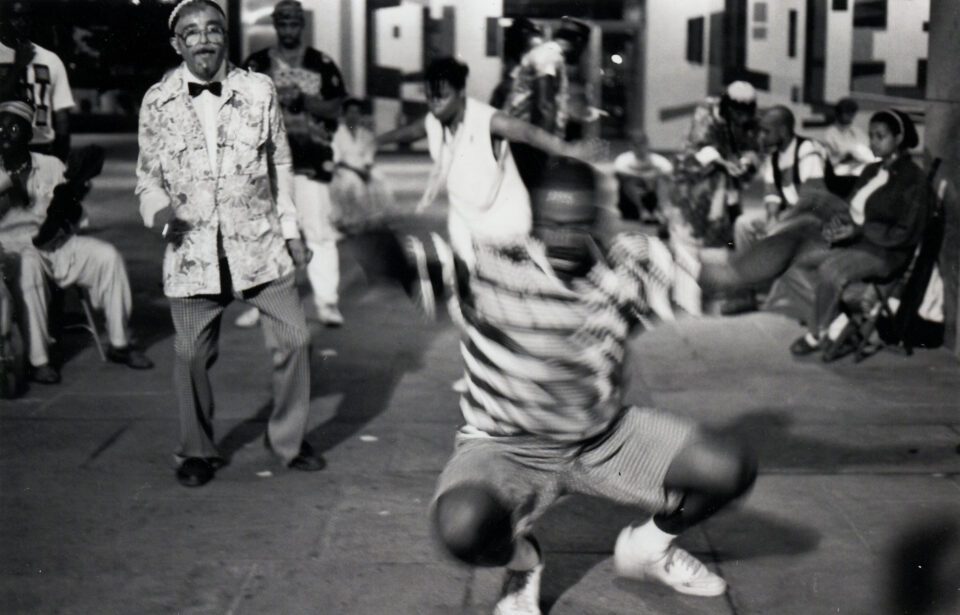

There is a rhythmic quality to the artist’s approach that reflects a personal love of music and dance. Smith likens the process of taking each photo to the creation of a score, noting: “I’m dealing with light, I’m dealing with all these elements, getting that precise moment. Getting the feeling – to put it simply, these pieces are like the blues.” For example, Sun Ra Space II (1978) depicts the jazz composer mid-performance in a radiant display of energy. Light speckles dance across the frame to transform Ra into something akin to the celestial. “For Ming Smith, the photographic medium is a site where the senses and the spirit collide. Calling attention to the synesthetic range of her photographic approach, this exhibition highlights how her images collapse the senses,” states Oluremi C. Onabanjo, Associate Curator at MoMA.

Smith’s experimental style has made her a woman of firsts: not only breaking boundaries in the Kamoinge Workshop but also at MoMA. In 1979, she became the first Black woman to have work in the gallery’s collection after answering an open call. David Murray in the Wings (1978) and Christmas Constellation, Brussels, Belgium (1978) – which were bought by the institution for less than their printing costs – now contribute to a far-reaching legacy. Smith’s mark is apparent in the next generation of artists who use photography to champion visibility of African American experiences. Tyler Mitchell’s (b. 1995) Chrysalis series, for example, highlights the contemporary New York landscape through reflections on Black beauty, desire and belonging. The same creative expression ripples through her body of work – in both her subjects and behind the lens. Projects: Ming Smith provides new recognition, and appreciation, for the artist’s previously undervalued contributions to the medium.

MoMA | Until 29 May

Credits:

1. Ming Smith, Sun Ra Space II, (1978). Courtesy of the artist. © Ming Smith.

2. Ming Smith. Womb, (1992). Courtesy of the artist. © Ming Smith.

3. Ming Smith, African Burial Ground, Sacred Space, from “Invisible Man.” (1991). Courtesy of the artist. © Ming Smith.