“To be a photographer is to seek light – without it, the lens is blind,” states author and writer Evie Tarr in the foreword to After Dark. However, Liam Wong’s (b. 1987) second monograph contradicts this notion, where darkness is a constant, relentless presence. It is both the background to his practice and a state of being. Inside, pages are blacked out with images emerging from them like scenes projected from a film reel. Monochromatic landscapes contrast against luminous street signs, and lone figures fade into the alleyways.

In After Dark, Wong reprises the highly stylised, neon- drenched street photography first debuted in TO:KY:OO (2019), which was the largest crowdfunded book in the UK. Whereas TO:KY:OO – whose title recalls the timestamp for midnight – focuses on a single city after nightfall, After Dark examines global nocturnal cityscapes. In Zaha Hadid’s Dongdaemun Design Plaza, Seoul, he captures urban, neo- futuristic geometry, whilst the “haar”, meaning sea fog, in his hometown, Edinburgh, departs from his distinctive style as part of his continued exploration of new environments.

Wong once hesitated to call himself a photographer, concentrating on his game design. In 2017, he made the Forbes 30 Under 30 as the youngest art director at Ubisoft, the titan game studio behind Assassin’s Creed and Watch Dogs. A trip to Japan in 2015 first inspired him to buy a DSLR camera and, whilst still working full-time on blockbuster titles like Far Cry 4, he continued to develop his photography practice. “It became this addiction,” he states, describing early images. “I was obsessively going out after midnight taking pictures.”

Five years later, he is recognised more for his photography than his 10 years as a game developer. Whilst design prepared him for the early hours, or “crunch culture”, photography is an equally demanding medium. “There’s a lot of gatekeeping.” Pixel peeping, for example, is a practice that involves digitally zooming in on images to find faults. Whilst he acknowledged the difficulty of experiencing this critique in an interview with Tim Jonze in The Guardian, Liam Wong’s Best Photograph (2020), it also encouraged his creative ambitions. “I started to think about what I go to photography for, and what I enjoy about it. And it goes back to video games.”

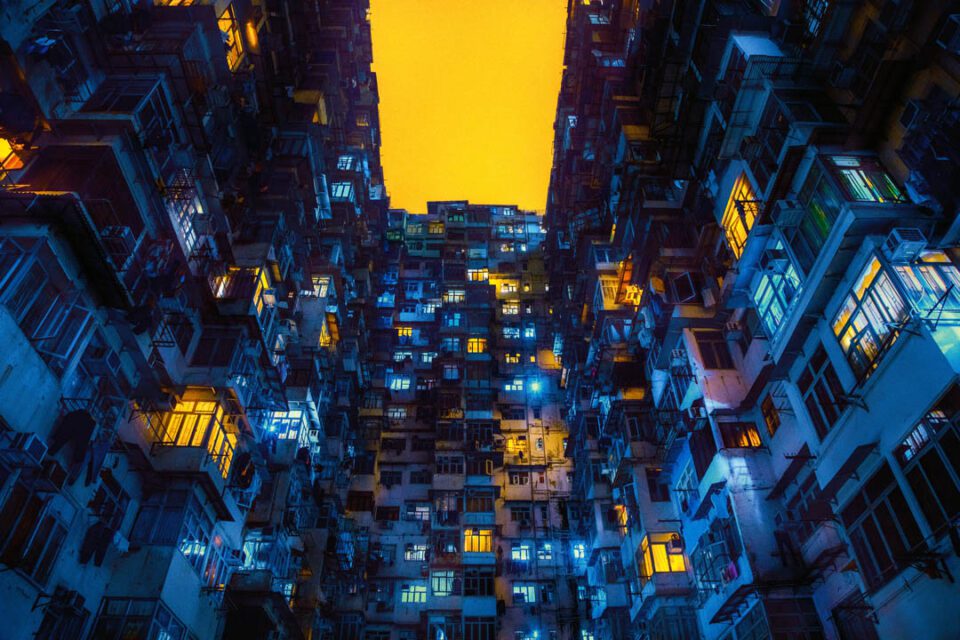

Wong’s photography is grounded in immersion, inviting the viewer to be part of the image. “I try to capture that feel- ing that you could have been there observing the same.” This approach informs his framing. Figures are “docked” to the left or right of an image, mimicking third-person video game cameras, whilst wide shots of subway tunnels place us firmly in the photographer’s shoes. Elsewhere, viewers stare up at Hong-Kong’s towering architecture, experiencing vertigo through After Dark: Quarry Bay, 03:22:25 (2022). Throughout, the image remains an avatar for our experience.

Gaming remains a useful analogy for his process. “I go to new cities and it’s like loading up a new game and exploring another world.” The images in After Dark are transportive because that’s how they are experienced behind the camera. “Liam’s photos are not just photos,” writes Hideo Kojima (b. 1963), the legendary video game designer behind Metal Gear Solid and Death Stranding. “You can feel what cannot normally be seen.” Wong, too, is more than just a photographer; his directorial and game development experience continue to influence how he reimagines reality.

Film is an important influence, especially in achieving this heightened sense of reality. After Dark is designed with “cinematic ratios” in mind, referring to Taxi Driver (1976), Blade Runner (1982) and Collateral (2004), amongst others. These films navigate urban environments, and he studied their composition, colours, swatches and stills to inform his photography. Park Chan-Wook’s poster for Oldboy (2003), for example, inspired TO:KY:OO’s cover image. ‘Minutes to Midnight’/23:58:32 (2019) depicts a lone man in the centre of the frame illuminated by purple and red street signs, harken- ing back to the neon-noir thriller. “I still say it’s my favourite film,” he admits. “Because of how it was shot. The audio, the acting, the tone. Everything about it. I like dark, gritty movies.”

He describes his work as neon-noir, citing Blade Runner concept artist Syd Mead (1933-2019) and cinematographer Roger Deakins (b. 1949) as creative influences. His cyber- punk cityscapes draw heavily on 1980s Japanese anime – which is also a genre of composites, from cyber-organisms to the evolution of cities to cyber-states – such as Akira (1988). A blend of science-fiction and film noir, After Dark in- habits a space halfway between in-camera and digital reality.

Born in Edinburgh to Scottish and Malaysian-Chinese parents, Wong’s dual heritage drew him to neon-noir as a genre. “There’s a lot of discourse around cyberpunk and Blade Runner. Because I’m half-Asian and half-Scottish, what I loved about Blade Runner was seeing this mix, this fusion of two cultures, which I had never seen before. And I gravitated towards that as an aesthetic.” Now, he has his own orbit: new and emerging photographers attempt to recreate his referential yet difficult to replicate style whilst CD Projekt Red com-mission reference art for AAA action game Cyberpunk 2077.

Whilst sci-fi shows us what the future might look like, noir obscures and shrouds, requiring an interloper who can expose the workings of this invisible underworld. His use of chiaroscuro lighting – displaying tonal contrasts between light and dark – is an essential element of film noir; it offers a moment of interaction between silhouette and environment, evoking a sense of surrealism. “I’ve definitely been into places, seedy spots, that I probably shouldn’t have,” he notes. But it was one of these locations that first provided him with a “cinematic” image. In Tokyo’s redlight district, his shot of a “taxi driver waiting in the rain for a couple to exit a love hotel” encapsulated a truly “real moment.” In After Dark, he continues to reconcile the unfamiliar and the illuminating.

“Over time, artificial light sources have encroached more and more upon the natural darkness,” writes Tarr. The future envisaged in these images is “post-dark”, in which sleepless cities are calibrated by 24-hour artificial lights. Wong recalls a passage from Paul Bogard’s The End of Night (2013) – which investigates the effect of light pollution on the natural world – regarding the Luxor Sky Beam in Las Vegas. “It’s the brightest light on Earth,” he says. “It affects the whole eco- system: the moths turning up, the birds eating the moths. A whole lifecycle is affected by this. I remember thinking differently about how I could structure this series of images.” Across abandoned streets and deserted alleyways, these background light sources denote the passage of time, evoking a sense of renewal and humanity’s continued existence.

“When I think about After Dark,” he says, “I think about capturing urban loneliness.” Motorbikes drive down deserted streets. Lone commuters walk beneath umbrellas and billboards. A single light illuminates an anonymous block of flats. “I was going to post an image set on Twitter, where women happen to wait on their phones: one under a neon sign, another in front of a convenience store. It’s them, their technology, and emptiness. I have similar ones of people passing through cities and these huge structures. First of all, why are the lights on? Secondly, there’s no one there to see them.” In the UK, where stores are turning out the lights in the face of rising energy bills, the unrelenting brightness of these images appear as an ominous invitation to a strange and abandoned world. “Being alone,” writes Tarr, “is something we both fear and crave. The silence of a place that is usually full of life can seem both morbid and precious.”

Nocturnal photography is as much about preserving the present as it is about elevating it to the realms of science fiction. Images of lone subway-goers recall Greg Girard’s (b. 1955) Tokyo-Yokosuka, 1976-1983 (2019), documenting the city’s late 20th century nightlife. These scenes act as artefacts, a space to admire “remnants of post-war scruffiness combined with a transitional modernity,” writes Girard. Wong also explores this physical transformation, preserving relics of the city lost to new innovations. For example, a location from Ghost in the Shell (2017), the live-action adaptation of the 1995 animated classic, has deteriorated. “Many of the original signs – with real neon rods inside them – are being replaced by new LED-lit signs because of safety concerns. The neon city is fading.” In pursuit of a cinematographic shot, he straddles the lines between past and present, to discover new locations and the emerging technology destroying it.

During lockdown, Wong took snapshots of buildings around Piccadilly in Call of Duty: Modern Warfare. He revisited them in Piccadilly Circus, London, 03:00:55, where an empty junction is illuminated by an electronic billboard advertising the game. This light source bled virtual experiences into the everyday, reflecting his attempts to obscure reality. “The ambiguity is deliberate,” he says when describ- ing the hyper-reality of his images. “The colours make you do a double take. You think: is that an illustration? No, it’s too realistic. Maybe it’s 3D concept art. That’s what I wanted to hone in on.” These scenes provide an illustrated yet inhabit- able universe, a contradiction that invites us to look again.

Photographers, then, act as private investigators: they bring the unseen to light. They reveal aspects of life that would otherwise go unnoticed: in Neon Alley, Seoul, 01:19:27, late- night revellers exit from a vending machine that doubles as a front for a hidden pizzeria. Even the wildlife remains anonymous, with Love Birds, Kowloon, 02:47:59 displaying two silhouettes suspended on a wire. “Ultimately,” he says,

“the photographs range from anonymity and intimacy to seclusion and privacy.” These contrasts are, as Kojima states in the foreword of TO:KY:OO, “a harmonious balance of beauty and disorder.” These seemingly opposite forces exist across artistic practices: reality and imagination; monochrome and colour; past and future; digital and analogue. Despite this futuristic vision, Wong highlights the importance of the traditional. “We’re in the age of social media,” he says. “When all of that dies, when Twitter and Instagram are gone and no one ever sees your work online, I’m still left with a book in a physical store that someone can stumble upon. I like that.”

Ultimately, if noir conceals the future and sci-fi reveals it, then Liam Wong’s photography in After Dark reconciles these contradictory impulses, exposing midnight’s quiet solitude.

Words: Jack Solloway

After Dark, Thames & Hudson | liamwong.com, thamesandhudson.com

Image Credits:

1. Liam Wong, After Dark, Quarry Bay, 03:22:25 (detail). From After Dark (2022) Thames & Hudson. © Liam Wong

2. Liam Wong, ‘TO:KY:OO Night Train’/00:00:00. From TO:KY:OO (2019) Thames & Hudson. © Liam Wong

3. Liam Wong, ‘Minutes To Midnight’ /23:58:32 (detail). From TO:KY:OO (2019) Thames & Hudson © Liam Wong

4. Liam Wong, Last train home, Tokyo, 00:39:45 (detail). From After Dark (2022) Thames & Hudson. © Liam Wong

5. Liam Wong, Warszawa po zmroku, Warsaw, 00:23:12 (detail). From After Dark (2022) Thames & Hudson. © Liam Wong