On an unspecified date in the 1960s, a young woman posed for a pin-up shot. Little did she know that decades later she would make an appearance in an artwork by Swedish artist Eva Stenram (b. 1976). If she were to see the image today, she might not even recognise herself. Only the legs are shown, one foot raised up, the other from the knee down, behind a white blind. In the original, the woman’s body features in full amidst the soft furnishings of a domestic interior. In the new version, Stenram has switched foreground and background, digitally extending the blind to obscure most of the figure – shifting the meaning entirely. It wasn’t a camera but the discovery of Photoshop in the late 1990s that sparked Stenram’s interest in photography. “I was fascinated by the ease in which I could mix different pictures together, causing folds in both space and time,” she recalls.

Stenram is amongst a wave of contemporary practitioners who, instead of capturing the world through their own lens, intervene in existing pictures, which they reuse and recompose. She features alongside 18 other artists in the group exhibition The Constructed Image, at The Ravestijn Gallery, Amsterdam. Jasper Bode, the gallery’s Director, developed the theme after noticing that several of his artists, including Inez & Vinoodh, Ruth van Beek and Koen Hauser, used fragmentary techniques, both analogue and digital. “I’ve always been interested in collage because you can push the hyperreality of what you’re looking at,” Bode says. “It lets you do things that in reality you can’t do.”

Still, artistic slicing and splicing isn’t new. It can be traced back to the early 20th century when Georges Braque (1882-1963) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) coined the term “collage” from the French verb coller, to stick or to glue. Cubist collage – using newspaper clippings and other materials – comprised a playful repurposing of found objects. The Surrealists, intrigued by psychoanalysis and dream theory, also used collage, much like automatic writing, to tap into the unconscious, unleashing meaningful juxtapositions between apparently unconnected elements. For the pioneers of photomontage, Dadaists such as Hannah Höch (1889-1978) and John Heartfield (1891-1968), it was a weapon of dissent. Höch deconstructed the sexism of the Weimar Republic from a female perspective, whilst Heartfield developed explicitly anti-fascist art by merging media cut-outs of Nazi politicians – a mantle carried forward into the 21st century by anti-war artist Peter Kennard or satirists like Cold War Steve.

Impressionist Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) de- clared that “photography freed painting from a lot of tire- some chores – starting with family portraits.” More than this, though, once there was a technological means to manu- facture faithful representations of reality, painters were no longer compelled by likeness and, from the early 20th cen- tury onwards, veered into various forms of abstraction. Simi- larly, now that everyone can take decent snaps with a smart- phone in their pocket, fine art photography has a newfound role to play. The borders have, if not dissolved, become more porous – democratised. In a 2016 article for the European Society for the History of Photography, titled Expanded Pho- tography: Persistence of the Photographic, art historian Lucy Soutter described how the medium has transcended the frame, unfolding into three dimensions. Even as it brings in elements of sculpture, performance, architecture and instal- lation, “expanded photography” retains an interest in the particular currency and history of still photography. This is what makes it a genre of its own, not simply contemporary art that happens to use photography. As KYoung, another participant in The Ravestijn show puts it: “There is an inherent ‘truth’ within the photographic source material; it lends cred- ibility and contributes to a suspension of disbelief, making it an invaluable tool. [From the start] my interventions allowed me to tell something beyond a single moment in space and time; it was a new way of thinking about image-making.”

In particular, the past decade or so has seen a resurgence of interest in photomontage and collage, with a flourishing in new variations of the form amongst contemporary prac- titioners. Julie Cockburn (b. 1966) who takes archival prints of portraits and embellishes them with embroidery and col- lage, transforming each one into a unique art object, is one example. Another is John Stezaker (b. 1949), whose surreal combinations of found film stills and publicity portraits won him the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize in 2012, a decision deemed problematic for some purists who disagreed that such a prominent award should go to some- one who didn’t himself “take” the pictures. These strategies are forms of manipulation, whilst not intended, necessarily, to deceive. This differentiates them from the murky world of deepfakes and filters, although they inevitably tap into those themes in the ways that they reassemble and reconceive.

The audience is savvy, still, in knowing that what they are witnessing is an alteration, or at least they should be, conceptually. “Unfortunately, the context sometimes gets lost, as the works spread,” says Eva Stenram. “A lot of people have assumed that I photograph models behind drapes. For me this would be totally uninteresting. The process itself – changing the picture by covering a model that used to be visible with the drape that used to be in the background – is for me what makes the piece intriguing and complex.” Stenram, who cites artists Man Ray, Claude Cahun, Brassaï and Hans Bellmer as abiding influences, identifies with the Surrealist idea of “disrupting reality from within.” For her, the act of modifying the vintage pin-ups reveals the voyeurism at play in the original. “I investigate how we look – by diverting the viewer’s gaze, removing the overt sexual content and playing around with the hierarchies within them.”

Reusing portraiture invokes specific ethical problems in relation to the subject of the original shot. Who were they? Does it matter? Are artists indebted to them? These are questions that Eva Stenram has considered at length. For Drape, she trawled online auction sites to procure the negatives of shots intended for publication in American men’s magazines. “It is not clear if they were ever published, where they were taken, or who the model and photographer were. I deliberately choose examples with minimal information. It is important to not know too much about their history,” she says. “I always attempt to make the original models anonymous. I don’t want my pictures to be about anyone specifically – this is about women, sexuality, photography and looking generally, not the models as individuals.”

This is an important distinction to make. In a sense, we’re all models now. Before the advent of the internet, we had greater control of the self we projected in public. Now screens are an ever-present fact of everyday life, we have become accustomed to seeing our faces projected online on Zoom or Facebook. Our representations have become slippery things, no longer in our grasp, as they circulate on social media. CCTV cameras around cities, outside shops, even on smart home tech such as doorbells, capture us on a daily basis. Our faces have become something, truly, other than our own and that’s something we all have to come to terms with in the years ahead. Whilst this isn’t necessarily the focus of artists such as those in The Ravestijn Gallery show, many of whom, like Stenram, are extremely conscious of how they use archival portraiture, it serves to remind us that our own likeness exists in a realm way beyond our consent.

There are legal, as well as ethical, implications in the ques- tion of ownership. Broadly speaking, the person who takes a photograph is its copyright owner, although in some cases, this could be transferred to an institution such as an archive or library. Copyright ownership remains with the photogra- pher even when posted on social media sites. However, by uploading a picture, you often unwittingly assign the right to the platform, be it Instagram or Facebook, to use it as it wishes. For example, by signing Twitter’s – probably rarely read – terms and conditions, you agree to let them “use, copy, reproduce, process, adapt, modify, publish, transmit, display and distribute” your photographs and posts.

This is problematic for professionals, who take a risk every time they share their work, although when it comes to artistic appropriation, the UK government has specific protections. Their website states that, “it is not necessary that a work is copied in its entirety – copying a ‘substantial’ part will also infringe … the courts tend to interpret the term ‘substantial part’ broadly, so even taking a relatively small part can be regarded as infringement.” KYoung outlines how this plays out in their work: “An obligation for sensitivity remains imperative when reusing found material. And, irrespective of the time-span between when the source imagery was made and then reused, as defined in copyright law, collage should only ever borrow, not steal, from the material it reimagines.”

And yet, KYoung also stresses, collage artists are engaging with something unique to our time. “It is fair, even essential, for artists to acknowledge the saturation of photographs that we encounter in everyday modern life.” According to analysis by Keypoint Intelligence over 1.43 trillion were taken in 2020 alone, 90% of them using smartphones. “And the act of reusing them within artworks is fundamental to identifying, documenting and exploring the social constructs surrounding where they sit within a particular time frame. Their inclusion in art serves as a future reference point. We only have to look back at Hannah Höch and John Heartfield to see just how important it will be in retrospect.”

Just as Höch and Heartfield questioned the social situation of their era, so many of these artists raise incisive points about our political reality. KYoung chooses not to disclose their gender identity “for the sake of impartiality.” One way of understanding their work is that it reflects new ideas about gender where predetermined, binary norms are rejected in favour of the right to define one’s own identity, mixing and matching elements that feel right. It’s an approach that’s also well suited to an age in which our survival requires us to reimagine what we have, instead of churning out more. We could think of this as a form of upcycling. In another 70 years’ time, who knows where that 1960s pin up may be. The story of an image is never complete, its legacy forever in flux.

Words: Rachel Segal Hamilton

The Constructed Image, The Ravestijn Gallery, Amsterdam. theravestijngallery.com

Image Credits:

1. Figure in Sofa, 2020 © KYoung / courtesy The Ravestijn Gallery.

2. Drape (Colour I), 2011 © Eva Stenram / courtesy The Ravestijn Gallery.

3. Drape (Centerfold II), 2012 © Eva Stenram / courtesy The Ravestijn Gallery.

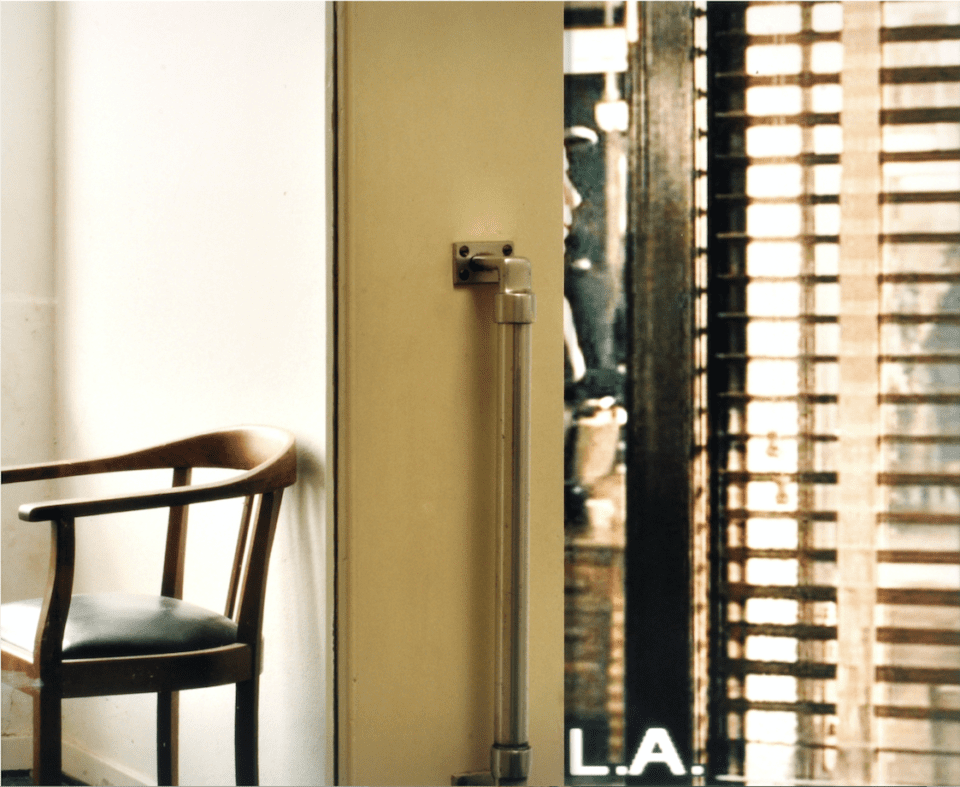

4. L.A., 2012, © Martina Sauter / courtesy The Ravestijn Gallery.

5.Figure in Sofa, 2020 © KYoung / courtesy The Ravestijn Gallery.

6. Green Curtains with Rug, 2020 © KYoung / courtesy The Ravestijn Gallery.