In 1969, a groundbreaking photographic initiative was conceived in the US. Its goal: to assess the state of the nation. Titled America in Crisis, the exhibition and publication turned a critical lens on the country at a time of great social, political and cultural change, examining events leading up to Nixon’s inauguration. Now, London’s Saatchi Gallery revisits the project, creating a dialogue between the original photographs and new works produced five decades later, during another tumultuous time in America. The resulting show sparks conversations around deeply rooted national debates concerning gun control, as well as topics of global impact such as the digital revolution, racial inequality and the climate crisis. Curator Sophie Wright discusses this new iteration of the project, and what it reveals about today’s interconnected world.

A: In this show, Saatchi Gallery builds on the original America in Crisis project, launched in 1969 by Magnum Photos. Call you tell us more about the initiative’s history?

SW: The original project was conceived for Magnum Photos by photographer Charles Harbutt and Lee Jones, Magnum Photos’ New York Bureau Chief. As Harbutt noted in 1970: “Several of us felt that the 1968 elections would be somehow special; that deeper questions for America were riding than just electing a president. I felt that the basic issue was that the traditional American self-image as learned through public schools, Hollywood movies, ads and Fourth of July speeches – the American Dream itself – was being challenged…”

It included work by 18 photographers, some of whom – like Mary Ellen Mark and Hiroji Kubota – weren’t members of Magnum at the time. It combined archival material with work from 1968-1969, up until Nixon’s inauguration. We have done the same with the contemporary work – using images taken before 2020. Harbutt curated the project in several formats. It was a book, which structured the project into chapters addressing themes such as The American Dream, The Deep Roots of Poverty, A Streak of Violence and The Battle for Equality. These are the headings we are using in the new version. A framed exhibition was shown at the Riverside Museum in Manhattan in 1969, along with an experimental film. There was also an interactive presentation using a gambling machine, which organised the pictures by chance. It was quite a statement; Harbutt intended it as a comment on the power of the media in shaping image consumption.

A: Why, in 2022, does it feel like the right time to revisit America in Crisis?

SW: In May 2020, I turned to my copy of the original America in Crisis book. It was clear that the issues being tackled in the project still had huge resonance for America. It remains the largest economy and democracy in the world and, particularly today, what happens there reverberates globally. Just look at the strength of the Black Lives Matter protests after the killing of George Floyd, and the focus for protestors on monuments such as that of General Lee in Virginia, photographed by Kris Graves. These protests spilled over into demonstrations in numerous other countries. It is important to revisit the works in an international setting, as exemplified by the exhibition here in the UK. We have had our own conversations about monuments, for example, with the toppling of the Edward Colston statue in Bristol.

A: This exhibition creates a unique dialogue between leading photographers from 1968 – such as Bruce Davidson, Elliott Erwitt and Mary Ellen Mark – and the works of 2020 contemporaries. Can you give some examples of new works, and how they speak to their 20th century counterparts?

SW: We have purposely concentrated on the contemporary photographers: the show is made up of about one third historical pictures and two thirds contemporary. We wanted, whilst honouring the work of Harbutt and the Magnum photographers, to give a platform to this new generation.

The American flag crops up throughout the project. One of the book’s opening shots by Harbutt, Main Street, has the flag sitting across a middle American street. It’s a way to set the tone – unpicking the American Dream versus American reality. Zora J Murff’s 2018 image Flagging, from his recent project American Mother, American Father is an interesting pairing with this one. The contemporary work in this exhibition ranges from very photojournalistic through to Murff’s much more open use of imagery, which sits at the edge of “documentary.” Murff uses found archival images, as well as his own photographs, to explore his personal relationship to the American Dream, to race and Blackness, and to status and success.

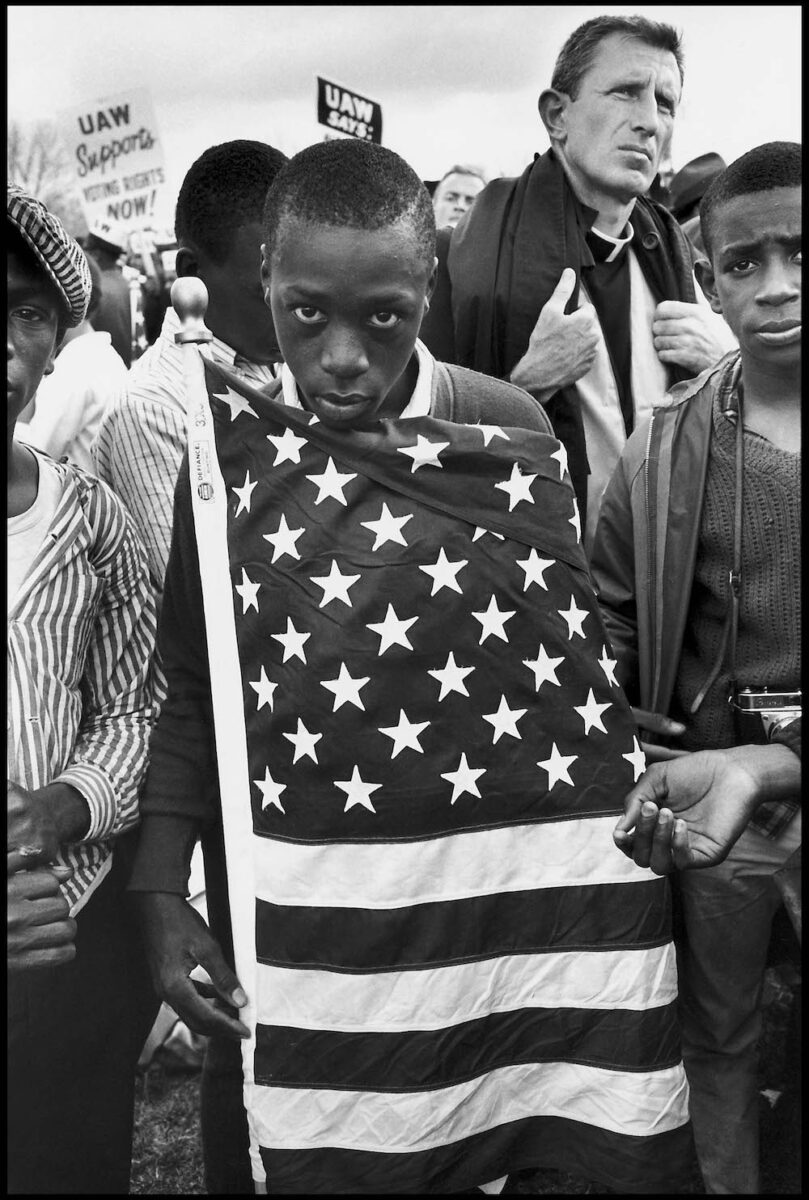

Matt Black’s extraordinary project American Geography speaks with well-known photographs of the Farm Administration by Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange. In this exhibition, we have placed Black’s work near Paul Fusco’s colour image of Cesar Chavez, the leader of the Californian grape strikes in the 1960s. Fusco’s piece of historical photojournalism is referenced by Black as being hugely influential to telling the story of poverty and disenfranchisement in America, that began, for him, in the Californian valleys. Elsewhere, Bruce Davidson’s images of the Civil Rights movement, particularly those of the Selma marches, resonate with work by Sheila Pree Bright, who documented Black Lives Matter protests in Atlanta.

Mary Ellen Mark is the only female photographer, aside from one image by Eve Arnold, in the original book. That is pretty representative of photojournalism in the 1960s, when it was predominantly white, western and male. The contemporary selections are much more diverse and there are a lot more women. It’s interesting to think about the work Mark was doing in Grant Park in Chicago, when protests erupted around the democratic convention in 1968, in the context of Leah Millis, a senior Reuters photographer who captured events in Washington on 6 January 2021. The crowds’ political leanings are quite different, but both women put themselves in the midst of the action to get their photographs.

A: What are the similarities – and differences – between the two generations of photographers? How has the medium developed over the last 50 years?

SW: This new iteration of the project needed to represent changes in the photographic landscape, and to highlight the breadth of practice now. We integrated this into the curatorial team. I’m London-based with a long history of working at a documentary photography agency. Greg is a curator at the High Museum in Atlanta. Tara is an LA-based photographer and academic. We all represent different ways of thinking.

The original project was produced at a time when there was still a belief in the photographer as an objective observer. Harbutt questioned that position later, falling out of love with documentary photography in the 1980s. These days, we are all more aware of subjectivity. Photographs can still play an important role in alerting us to issues, but we are more conscious of who is taking the picture and what or whom they represent. Photography is a slippery medium, and it’s one that we are all engaged with these days – taking and publishing pictures with iPhones. That can be hugely empowering and important in holding people to account. What happened to George Floyd was filmed on a handheld device and circulated to millions. Yet the way in which images are presented to us can change their meaning.

Photography is often lazily called a universal language, and in one sense it is, but context makes a huge difference to how we understand pictures. This includes the text or story they are edited into. So, in this exhibition, we are asking our audiences to think about image culture. A video installation at the end references the hidden structures behind how we view images digitally. Algorithms reinforce our existing perspective on the world and, at a time of huge polarisation, exacerbated by social media, we all could do with thinking more about how we understand and consume images.

A: How did you approach the task of choosing which images to include?

SW: The curatorial team worked on the historical images first, knowing that we wanted about one third of the exhibition to be comprised of them – and that we probably needed to narrow down the selection. There were some obvious names to include such as Davidson, Erwitt, Harbutt – who conceived the project as a whole – and Mark, as the only female photographer. Then, between the three of us, we reached out to contacts to suggest contemporary names to look at. Had we covered all the issues? Was the selection representative enough in terms of who took the pictures and the types of photography?

A: Whilst this exhibition focuses primarily on America, do you think it will resonate globally?

SW: “Crisis” is a very loaded term, but I think we all understand its meaning after the past two years. The pandemic has been challenging for all countries and accelerated societal changes that were already underway. We have, for some time, been witnessing a shift in the global balance of power. Perhaps it represents the end of a particular 20th century view of “history as progress”, and of America as “leader of the free world”. The project reminds us that if we are to make positive change and learn from our mistakes, we must understand the origins of our problems.

America in Crisis, organised by Saatchi Gallery, opens from 21 January to 3 April 2022. The exhibition is curated by Sophie Wright, Gregory Harris from Atlanta’s High Museum of Art, and academic Tara Pixley. Find out more here. For tickets, click here.

Words: Eleanor Sutherland

Image Credits:

1. Massive Support for Richard Nixon at the Republican Convention. Miami, Florida, USA, 1968. © Elliott Erwitt/Magnum Photos

2. Grant Park, Chicago, 1968 © Charles Harbutt

3. The Selma March, Alabama, USA, 1965. © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

Lead image & 4. #FXCK July 4th: Rally cultivating change from injustice and police brutality toward women and LGBTQ+, Atlanta, Georgia, 2020 © Sheila Pree Bright