MoMA dismantles the narrative of photographic history, focusing on an understudied chapter from the heart of São Paulo in the mid-20th century.

Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946–1964 is the first major museum exhibition of its kind taking place outside of Brazil. On view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, from 21 March, the show focuses on the unforgettable creative achievements of São Paulo’s Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante: a group of amateur photographers widely heralded in Brazil, but essentially unknown to European and North American audiences. Sarah Meister, Photography Curator, expands on the exhibition’s key themes and the controversial history of this pioneering collective.

A: The Foto-Cine Club Bandeirante was established in São Paulo in 1939. How did the group come together?

SM: The founding of the Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante (FCCB) is a tale rehearsed regularly in the pages of the Boletim, the club’s monthly magazine. A typical account would describe “a small group of idealists” gathering at a photographic materials store in downtown São Paulo. They chose their name because bandeirante “was the name given to the men of São Paulo who explored the backlands of Brazil; for these new Paulistas would be the new bandeirantes [exploring] art photography across Brazil.” Today we recognise how problematic it is to speak in such glowing terms about a group of “standard-bearers” (the literal translation of bandeirante) whose adventurous spirit resulted in the enslavement of Indigenous people, the overwhelming expansion of territory under colonial control and the exploitation of natural resources. Yet the standard FCCB narrative overlooked this reality, aligning their pioneering efforts with these historical figures.

A: Who were the key figures leading the group and how would new members find and approach the collective?

SM: Eduardo Salvatore was president of the FCCB from 1943 until 1990. Salvatore’s formidable leadership qualities arguably eclipsed his artistic talent, but he championed important work amongst peers. He fostered an environment in which competition and criticism encouraged innovation, and he made sure that these achievements were celebrated in Brazil and globally. The club’s reputation – encouraged through annual international salons, the Boletim and considerable attention in the local and international press – made it easy for anyone serious about photography to find one another.

A: What were the key aesthetic or formal qualities heralded by the group? How did the club respond to the history of the medium and envision its future?

SM: In 1951 Salvatore proudly declared: “At FCCB, we are never satisfied with the work we do and always want more; it is progress we are after: new themes, subjects, forms of expression. In fact, we are witnessing a clash between two mindsets: old ‘pictorial’ photography (so called because it imitates static, lifeless, academic painting) and a new, more photographic, more vigorous mentality, replete with life and humanity, bold angles and plays of light, and enjoying the photographic process along with all the characteristics that make it unique and distinctive.” This perspective was not quite as ubiquitous as Salvatore perhaps made it seem, although the 140 photographs in this exhibition (and accompanying book) convincingly capture this sense of spirit and passion.

A: These individuals began working at the beginning of WWII; what were the socio-political contexts of Brazil at this moment? How did this feed into the group’s ideas, and bookend the period presented at MoMA?

SM: The dates that bracket the temporal scope of the exhibition correspond to artistic, political and practical realities in Brazil: 1946 was the year the FCCB first published its Boletim; it was also the year in which a new constitution was adopted and democracy restored, following Gétulio Vargas’ repressive Estado Novo regime. On the other end, 1964 marked the beginning of a brutal military dictatorship that would last more than two decades. By that time, the innovation and creativity associated with amateur photo clubs around the world was already on the wane, and the censorship and repression ushered in by the dictatorship marked the end of an extraordinarily fertile era for photography in Brazil.

A: When was the FCCB’s most creative period?

SM: In October 1951 the Boletim references a “new school of art photography,” the beginning of a wildly creative period. By 1955 the term Escola Paulista (Paulista School) appears to have been broadly adopted. In a review of a solo exhibition by Marcel Giró, the Boletim reported: “Giró is undoubtedly one of the leading representatives of this type of photography, which has stood out for its bold angles and compositions, its play of lines, light and shadow.” Although the Escola Paulista is not, by definition, synonymous with the FCCB, there is a perfect overlap between individuals associated with the group and the movement. Alas, almost as soon as FCCB had achieved fame, quotas, import duties and other economic challenges began to take their toll.

A: Who were the photographers most influenced by? Do they cite certain movements or media? How important did the FCCB find artwork made as a cultural response?

SM: The group was keenly attuned to artistic developments across various media and borders. The FCCB’s work was displayed prominently in the second São Paulo Art Biennial (1953-1954), and they would regularly invite leading practitioners and critical thinkers – from Waldemar Cordeiro and María Freire to Mário Pedrosa and Walter Zanini – to speak at the club’s headquarters as well as commission, translate and reprint articles from a wide variety of newspapers and magazines, both domestic and international. The cities of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and (beginning in 1960) Brasília were filled with buildings by notable architects that were their own source of creative inspiration. Their work resonates convincingly with contemporary achievements in the USA, France, Germany and elsewhere, although I would argue that these were parallel achievements, not influences.

A: When did the collective begin to gain recognition, validating modern Brazilian photography in the eyes of many curators, institutions and countries?

SM: As early as 1946, the FCCB was invited to join the Photographic Society of America (PSA), rightly taking it as a signal of their arrival on the international scene. In May 1950 they were one of two non-European groups invited to become founding members of FIAP (Fédération Internationale de l’Art Photographique). Photographs by members of the FCCB were awarded prizes in amateur salons across six continents. Despite this widespread recognition at the time, their achieve- ments were all but forgotten outside of Brazil, that is, until now.

A: Why do you think these figures have been forgotten or left out of the artistic canon? What critical issues does this raise in terms of representation and recognition in the art world, in the 20th century and beyond?

SM: Perhaps the two greatest biases that affected – and apparently continue to affect – the reception of the work were the twin beliefs held, consciously or not, by the cognoscenti of cultural capitals across western Europe and the USA. The first of these ideas was that art produced in the “peripheral” zones of the globe was necessarily derivative or else hope- lessly out of step with the aesthetic discourse of the day. Second was the notion that the amateur, whether in Paris or New York or in “peripheral” cities such as Lagos or São Paulo, was likewise condemned at best to produce convincing simu- lacra of the advanced art of their time or at worst to traffic in the shopworn, whether clumsily or with uncommon technical finesse. The peripheral and amateur, no matter how accomplished, carried the inescapable musk of the second-rate.

A: This is the first FCCB show outside of Brazil; how does it fit within MoMA’s programming and curatorial plans?

SM: From its privileged position in New York, The Museum of Modern Art has long dominated the ways in which the history of modernism is told, a story that has over time been distilled into a neat progression. This narrative is, however, at odds with any close reading of the historical record, and MoMA is now committed to dismantling this widely accepted documentation. This show is an opportunity to highlight extraordinary achievements, and also to reflect on the structural and aesthetic hierarchies that have contributed to their absence from histories of modernism outside of Brazil.

A: How have you brought to light FCCB’s key principles?

SM: Both the book and the exhibition present the work of six photographers in depth – Gertrudes Altschul, Geraldo de Barros, Thomaz Farkas, Marcel Giró, German Lorca and José Yalenti – offering audiences an opportunity to appreciate a wide spectrum of achievements. However, to experience the full scope of the club’s vibrant heyday, it is essential to share examples of equally compelling work by dozens of other members who toiled in the same darkroom and submitted their prints to the same salons. The images are organised in groups according to the club’s concursos internos (internal contests), but also with focused presentations of individuals.

A: The FCCB is just one artistic group classed as “amateur” despite pushing multiple boundaries. Photography is now widely accessible; individuals across the globe can shoot and publish work without professional or academic training. How are the goalposts shifting?

SM: The widespread compulsion to articulate and defend what it is that makes a “good” photograph is itself an under-studied thread that connects the artists of the New York- based Photo-Secession (who sought to distinguish their work from the hordes of professionals and Kodak-wielding amateurs at the turn of the 20th century) to the postwar photo-club circuit, and it is close to the heart of MoMA’s history and evolving attempts to define what is worthy of being considered and recognised as “modern art.” The near-complete exclusion of these figures to date, in light of their irrefutable appeal, should also be understood as a critique of this institution’s – and my own – vexed efforts to make sense of the marvellously sprawling, unruly medium of photography.

Words: Kate Simpson

Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946–1964. MoMA, New York, 21 March – 19 June.

moma.org

Images:

1. Julio Agostinelli. Circus (Circense). 1951. Gelatin silver print, 11 7/16 × 15 in. (29 × 38.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of Richard O. Rieger. © 2020 Estate of Julio Agostinelli.

2. Thomaz Farkas. Ministry of Education (Ministério da Educação) [Rio de Janeiro]. c. 1945. Gelatin silver print, 12 13/16 × 11 3/4 in. (32.6 × 29.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the artist.

3. André Carneiro. Rails (Trilhos). 1951. Gelatin silver print, 11 5/8 × 15 9/16 in. (29.6 × 39.6 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of José Olympio da Veiga Pereira through the Latin American and Caribbean Fund. © 2020 Estate of André Carneiro.

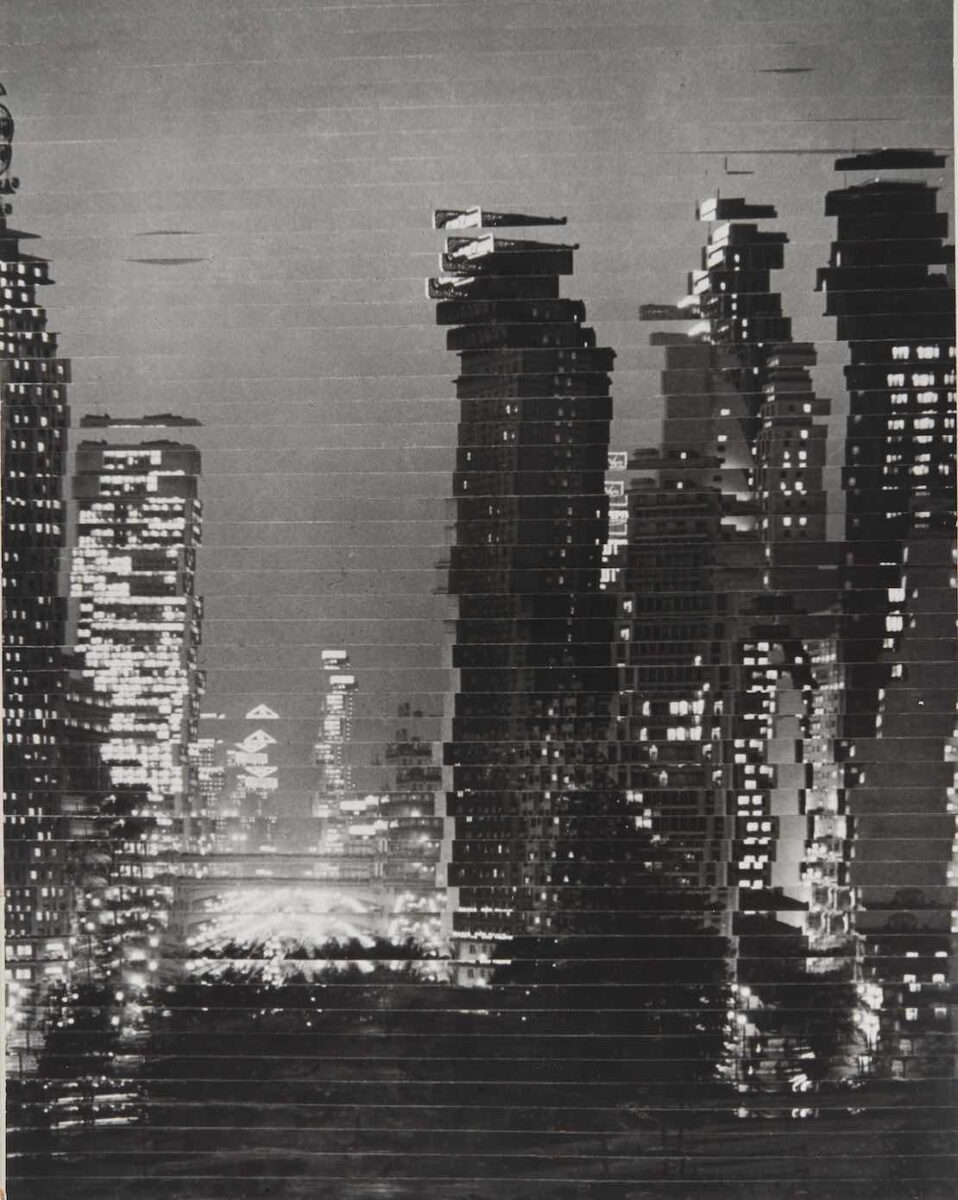

4. Roberto Yoshida. Skyscrapers (Arranha- céus). 1959. Gelatin silver print, 14 9/16 × 11 9/16 in. (37 × 29.3 cm). Collection Fernanda Feitosa and Heitor Martins. © 2020 Estate of Roberto Yoshida.

5. Broken Glass (O vidro partido). c. 1952. Gelatin silver print, 11 7/8 × 11 1/2 in. (30.2 × 29.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of Donna Redel. © 2020 Estate of Maria Helena Valente da Cruz