Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg’s (b. 1982) artworks explore our relationship with non-human life, considering how the natural world might evolve in a “post-biological future” – one that human beings are creating. Her project Better Nature (2009-2015) paired artists and designers with synthetic biologists to envisage a range of bioengineered species. Now, the Eden Project has commissioned Ginsberg to create a major new permanent installation in its outdoor gardens. Launching later in 2021, her algorithm-based planting project will draw attention to pollinator decline and explore how we can counter the problem.

A: What do our readers need to know about pollinator decline, and why have you chosen to focus on this issue?

ADG: Pollinators are utterly essential to life on Earth, enabling the plants that have evolved alongside them to reproduce. They support life as we know it. But over the last 30 years, global insect populations have crashed by 25%. Whilst the threats that honeybees face are increasingly publicised, they are not the only pollinators. In the UK, 24 species of wild bumblebees, 230 solitary bee species, as well as moths, butterflies, flies and wasps all play a crucial role in pollination. The pollinator commission is part of a larger programme at Eden called Create-A-Buzz, funded by the Garfield Weston Foundation, bringing attention to these pollinators’ alarming decline.

A: Your new installation for the Eden Project’s outdoor gardens uses algorithms to create pollinator-friendly planting schemes. Can you tell us how the project will work?

ADG: Given the chance to create a work for a 52m-long piece of the Eden’s Projects gardens, I suggested that rather than an artwork about pollinators, we make an artwork for pollinators. Moving outside of the gallery, could we fabricate a digital artwork in flowers?

The way we see the world is just one version of reality. For example, different pollinators see different colours to us, influencing the colours of the extraordinary variety of plants they serve. The artwork began with seeking a way into the shared reality of plants and pollinators; it is a search for empathy for the more-than-human. Rather than designing gardens for us, what does a garden created from a pollinators’ perspective look like, and how can we make one? The result is an algorithmically designed garden optimised for pollinators, not human aesthetics.

I wanted the algorithm to maximise empathy. I was then faced with the challenge of turning that idea into something that could be coded by Dr Przemek Witaszczyk, a brilliant string-theory physicist with whom I have worked before. I decided we would define “empathy” as maximising the diversity of different pollinator species.

The algorithm selects plants from a palette of perennials curated with horticulturists at Eden and pollinator experts. First it selects plants that match Eden’s conditions from this database, then generates unique pixelated garden designs that serve as many different species as possible, from long-tongued bumblebees to butterflies. For example, it optimises the plant choices to maximise blooming across seasons, whilst making patterns to suit different foraging strategies. The algorithm assigns a plant species to each pixel square, which is then translated to plants in the ground.

A: You have also created a website where UK audiences can use algorithms to create their own planting schemes. What was the thinking behind this?

ADG: The ambition is to create more than an artwork: an art-led campaign. We are putting the algorithmic tool online so anyone can create their own unique artwork for pollinators – a garden planting scheme – which they can plant if they have a garden or community space. They can make their own DIY edition of the artwork, complete with an edition certificate downloaded from the website.

We want to make a network of sister artworks for pollinators around the world, large and small. Empathy and generosity are at the heart of this. We are looking for international museums, botanic gardens, or collectors to commission large “Edition” gardens. For each, we’ll create a new regional plant database suitable for the garden’s location, which will be donated back to the website. This in turn will allow visitors to plant their own local DIY editions, seeding a garden network.

A: What role do you think art can play in helping us to imagine new ways of living alongside non-human animals such as pollinating insects?

ADG: An artwork won’t save pollinators. I’m experimenting instead with how art can be used to give people agency to do something amidst the ecological crisis we have created, not just feel a sense of panic and loss. The dedication needed to care for a garden allows us to connect more deeply with plants and their pollinators. Making an artwork for the more-than-human invites us to see the world from their perspective. Art doesn’t need to be useful, but it can be transformative. I was really motivated by Eden’s mission to inspire not only a sense of jeopardy about nature, but also connection, hope and agency in its visitors.

A: Could you tell us about the role that technology plays in this work? Are there ethical questions to answer about how we interact with artificial life as well as animal life?

ADG: Using an algorithm to make garden designs meant we could do some fiendish computation as well as reduce some human aesthetic biases. Of course, no algorithm is neutral, since every decision made in building it requires a human decision and the data it draws on is also assembled by humans. We can’t escape our own touch.

I have made other works that use machine learning (Machine Auguries, 2019) and explore AI (The Substitute, 2019), which both frame the paucity of artificial life compared to the intelligent life that already exists. That said, they also tease us with the thrilling possibilities of these new technologies and our fascination with lifelikeness that intrigues us, from the Golem to Frankenstein’s monster. I’ve spent a lot of time exploring “lively” technologies: I’ve worked with synthetic biologists since 2008-2009, learning how engineers are manipulating life, transforming organisms into biological machines to make useful things for humans. The ethics of the desire to control life is a question I explore often in my work, such as in Designing for the Sixth Extinction (2013-2015).

I am particularly fascinated by the current preoccupation with creating new life forms, while neglecting existing ones. We absolutely must challenge the technologies that we make and ask who they serve, and who benefits from their existence.

Audiences can be part of Eden Project’s unique artwork. Ginsberg is encouraging viewers to create, plant and share their own garden and planting scheme, designed for bees and other insect pollinators, using the new website and algorithm pollinator.art.

Words: Greg Thomas

Image Credits:

1. Video still from The Substitute, 2019. Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg. Visualisation/animation by The Mill.

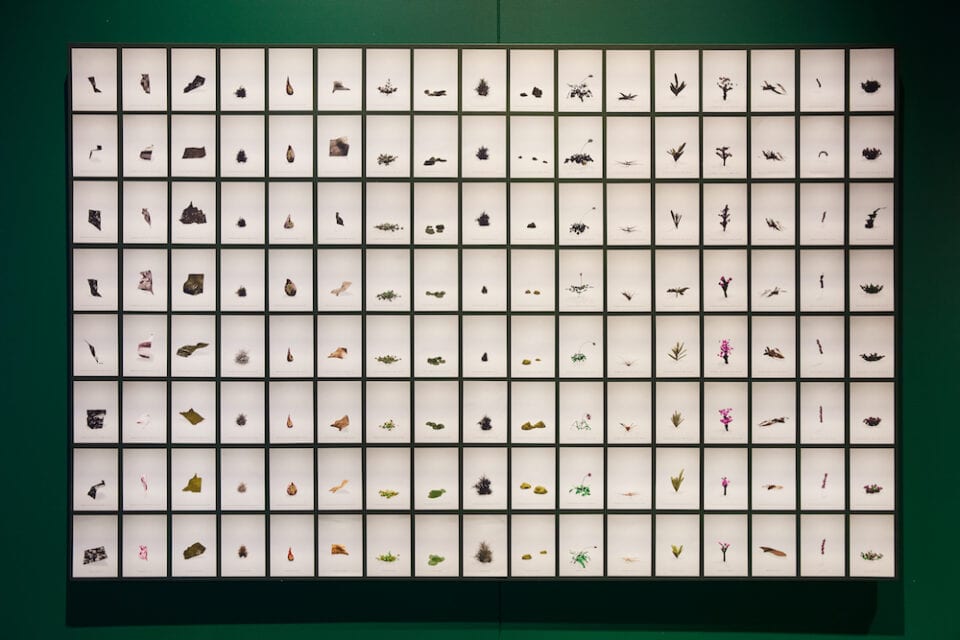

2. Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, The Wilding of Mars, installation view at Moving to Mars, The Design Museum, London, 2019. Photo credit: Photo: © The Design Museum, Ed Reeves.

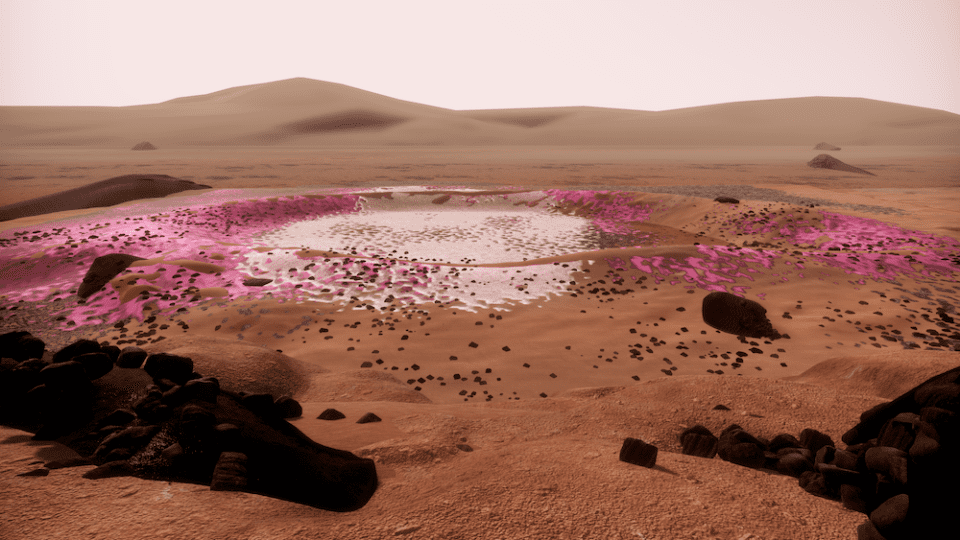

3,4,5. Simulation shots, The Wilding of Mars, 2019. Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg.

6. Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, The Wilding of Mars, installation view at Better Nature, Vitra Design Museum Gallery, 2019. Photo: © Vitra Design Museum, Bettina Matthiesen.

7. Preparatory sketch by the artist, 2020. © Dr Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg.