Ori Gersht (b. 1967) is known for destroying painstakingly recreated versions of iconic classical paintings on camera. The London-based, Israeli-born artist is interested in time periods involving revolutions – the scientific, industrial and digital – which he posits as crossroads that define photography. Throughout his career, Gersht has observed the relationships between history, landscape and memory.

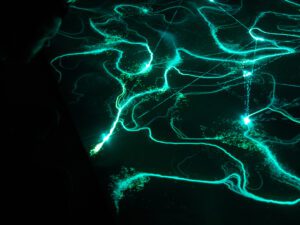

Fruit explodes and flowers shatter in slow-motion videos, inviting conversation around digitisation, reality and virtual spaces. The resulting imagery is unsettlingly beautiful; viewers are drawn in before being confronted with darker and more complex themes. Gersht adopts a poetic, metaphorical approach to explore the difficulties of representing violent events or histories. Blow Up (2007-2008) transforms the 19th century work of Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904) to examine nationalistic discourse, whilst Big Bang (2006) recalls 18th century Dutch still life, the illusion of a flower bouquet shattered in a slow-motion explosion, evoking an image of the creation of the universe and the cycle of life and death.

Gersht now turns his focus to the relationships between photography, optical perception and technology in Fields and Visions and Another World (2022). These works incorporate Artificial Intelligence to reform and reshape low resolution photographs at a time when digital advances are both propelling and challenging contemporary image-making. These uncanny depictions question artistic representation and the truth behind a visual. Gersht continues to foster dialogues between art history and contemporary practice, whilst also pushing beyond the borders of new technologies.

A: You are renowned for responding to 17th century still life paintings, including those of Jan Brueghel the Elder. What is the significance of this genre and flower motifs?

OG: We all have an immediate connection with flowers. We connect them to Valentine’s Day but also to memorials and graves – they relate to such a broad range of our emotional experiences. From the very early days until now, flowers have performed a significant role in visual art. There are so many ideas that can be played out very subtly through their use: historical, political and ideological questions. All this can be hidden behind their delicate, formal beauty. Jan Brueghel the Elder’s (1568-1625) paintings were some of the first of their kind. They mark a transitional moment when painters stopped including native wildflowers in their work. Instead, all the flowers were cultivated. They would not have existed without human intervention, as they never grew – naturally – in the same place. It is a movement away from the “real,” as species from across the world started to arrive in Europe. Brueghel is already asking questions about nature and human intervention. I’m doing the same but in the digital age.

A: Your practice is deeply rooted in photographic history and pivotal moments that changed visual culture forever. Can you discuss the time periods that have inspired you?

OG: I tend to look at three revolutions in my work: the scientific, industrial and digital. Crossroads that really define photography. Each one of them was a leap that changed our understanding of the world. Magnifying lenses were invented during the Scientific Revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries. This was when Galileo started to look at the celestial skies – he was able to produce drawings of the moon that challenged perceptions. People believed the moon was a perfect spherical body, but Galileo’s observations enabled us to see craters. We could look through a microscope and see organisms invisible to the naked eye. The lens became an extension of human vision, giving us access to the large and the small. I consider this moment as one where space is compressed. The Industrial Revolution (1760-1840) is another such period – steam engines and factories began to exceed our biological pace. Photographic chemistry was invented in the 19th century, altering our notion of linear time by freezing a moment. Now, we are in the Digital Revolution, which I see as a complete collapse of time and space.

A: Time and speed are frequently explored in your work. Your projects have documented bullets hitting pomegranates at 1,600 frames per second. Where does this interest in representing and altering time come from?

OG: My fascination with time – and the camera – probably derives from my own sense of mortality. Photography can harvest time, turning the present into something eternal. It records moments in transition. Like Schrödinger’s cat, these paradoxical scenarios exist – simultaneously – in two states: holding together and falling apart. I record events that occur in the folds of time, taking place at an enormous speed that the mind can’t process. These “phantom” events can be considered metaphysical since they occur outside of human perception. However, with the aid of new photographic technologies, such moments are becoming visible. The question is: if we are unable to experience something, does it exist? And what does it mean to witness an event that can be captured by the camera, but not seen by the naked eye?

A: Can you discuss the myriad socio-political meanings that flowers manifest across your body of work?

OG: My Blow Up (2007-2008) photographs are based on paintings featuring the three colours of the French flag: red, white and blue. On first glance, the original 19th century works by Henri Fantin-Latour seem comfortable and bourgeois. However, looking deeper, there’s a nationalistic discourse invested in them. Blow Up takes this subject matter and colour palette, transforming them into a series of explosions, with all the political implications that brings. Fragile Land (2018) is based on flowers on the verge of extinction in Israel: Cyclamen, Iris Atropurpurea and the Madonna Lily. The plants are involved in the political conflict. People are supposed to protect the flowers to protect the land: where they grow is a place everyone respects. This is a moment where nature does something extraordinary, connecting us to a location and encouraging us to look beyond the desire for nationalistic ownership. In On Reflection (2014), I thought about glass breaking as an act of cultural violation. I kept in mind the horrific scenes from Kristallnacht on 9 November 1938, when Nazi sympathisers went out into the streets of Germany to smash shop windows and burn Jewish books.

A: What does the process of assembling and destroying one of your pieces look like? How long does it take?

OG: On Reflection (2014) took close to 18 months to see through. With the help of my studio team, we used synthetic materials – plastic, paper and silk – to recreate Brueghel’s bouquets, replicating the original painting as closely as possible. Then, I put mirrors in front of them; what we ended up looking at was a reflection. I used two cameras standing beside each other, each with a different focal point. One looked at the “virtual space” (the reflection), and the other recorded “reality” (the material of the glass). Finally, after all this effort, I destroyed the piece in a flash, whilst capturing it in slow-motion. The act of destruction is fundamental to my practice. The idea is to turn it on its head – for demolition to become an act of creation. This dialectical relationship is integral. I turn moments of obliteration into new possibilities.

A: Another World and Fields and Visions (2022) incorporate AI. What is the inspiration behind these works? Why did you choose to add “computer vision?”

OG: I have returned to the botanical themes that occupied me for the last decade. Inspiration derived from Swiss naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717), who travelled to Suriname in the 17th century to study its native tropical plants. The project also draws on American painter Martin Johnson Heade (1819 -1904), who toured the Amazon in the 19th century in search of hummingbirds and exotic orchids. Both artists returned with souvenirs from the regions, and subsequent drawings depict new species of floral and fauna previously unknown to American and European audiences. In doing so, they expanded scientific and cultural knowledge, fusing fact and fiction to build a mysterious world that ignited imaginations. For Another World and Fields and Visions, I reproduced the same locations in my studio. I made the images at a very low resolution because I wanted to fill the gaps using artificial intelligence software. I enlarged small photographs to a massive size, inviting the computer to use its acquired knowledge to imagine the lost information. These images are no longer faithful depictions of physical matter but hybrids: partly optical, partly digital. I find the question of what is real very interesting, since the notion of reality is fluid. This work presents a shift in the discourse of authentic photographic vision, redefining ideas of “realism.”

A: Discussions of AI image generators, avatars, the metaverse and NFTs have dominated headlines for the past few years. Do you think we are still living in the Digital Revolution? Or are we entering a brand new era?

OG: We are still living in the revolution. Everything around us is unstable: rapid changes, continuous transitions, social and political paradigm shifts. The Digital Revolution is throwing everything up in the air. This is very scary, but simultaneously it is an exciting moment. There is no doubt that a new era is ahead. It could be that we are coming to the end of the optical era, with volumetric captures and virtual experiences that are starting to provide more and more possibilities. We have been striving to create lifelike representations of the world for centuries: first through the medium of painting, then photography, film and now virtual hyperrealism. Step by step, we are getting closer. At the same time, we are losing ground and distancing ourselves from visceral experiences. That’s why paintings are particularly attractive right now; they connect us with our bodies and the physical world. Painting remains like a lifebuoy, to some extent keeping the tangible presence of art above water. Yet, I believe virtual art will become a dominant force in the years to come. Notions of reality and truth will have to evolve and find new forms.

Interview first published in Future Now Aesthetica Art Prize 2023

Words: Eleanor Sutherland

Image credits:

1. Ori Gersht, Blow Up 01, (2007). Courtesy of the artist.

2. Ori Gersht, Blow Up 04, (2007). Courtesy of the artist.

3. Ori Gersht, New Orders 01 – Untitled 01, (2018). Courtesy of the artist.

4. Ori Gersht, Pomegranate: Off Balance, (2006). Courtesy of the artist.

5. Ori Gersht, Blow Up 17, (2007). Courtesy of the artist.