In September 2022, Londoners were dismayed to hear of the forthcoming closure of legendary cultural and music venue, Printworks, which was also considered one of the world’s best clubs, located in the capital’s Docklands area. The space’s rave-industrial aesthetic is reminiscent of iconic Berlin club Berghain and, housed in a building that originally contained a printing facility, it has drawn massive crowds since its 2017 launch. Its iconic status solidified upon transformation into The Iceberg Lounge set, the nightclub owned by villain The Penguin in the The Batman (2022), directed by Matt Reeves.

The venue is one of several projects by Broadwick Live, also the group behind the Field Day music festival and The Drumsheds. These are renowned for starry lineups of electronic music and generating vigour in an increasingly sluggish club and rave culture that was deadened by the pandemic. Now, Broadwick’s latest venture is The Beams, a 55,000 square-foot industrial warehouse space on Factory Road in East London’s Royal Docks. The newly-converted music and culture venue, which opened in October 2022, has already hosted Honey Dijon, Maceo Plex, Skepta and Skream. This year, it offers its first contemporary art programme.

Titled Thin Air, it is a gargantuan, walk-through immersive art experience. Brooklyn-based digital artist and curator Alex Czetwertynski known especially for his work melding live music environments with sensory experiences, brings together seven contemporary artists and studios whose work fuses art and technology. Artistic duos 404.zero and Kimchi and Chips, with Rosa Menkman (b. 1983), join collectives SETUP and UCLA Arts Conditional Studio, alongside solo artists Matthew Schreiber (b. 1967), Robert Henke (b. 1969) and James Clar (b. 1979). The show arrives as part of a strategy from Broadwick for both The Beams and the Dockyards, one of their nearby spaces, to exist beyond the realm of music and parties. Most clubs are empty during daylight hours, but these venues utilise this down time to bolster new forms of artistry – hosting film sets, video productions and more. Thin Air is a seminal exhibition that highlights potential future directions for multidisciplinary art.

“One of the things we were interested in for this first iteration was the idea of things appearing and disappearing, revealing something through their ephemeral presence,” shares Czetwertynski. “The artists deal with the revelation of a form through a material that cannot be touched, but that feels tangible.” It’s this notion that underpins the title: physicality is not the focus but a means to a state of mind, a manufacturing of events so focused they render the immaterial material.

For instance, the biggest installation, 3.24 by 404.zero, is described as “architecture in motion,” an ever-shifting environment that “shuffles through a series of existential experiences by redrawing the space through light.” The collaborative duo comprises Kristina Karpysheva (b. 1984) and Aleksandr Letsius (b. 1984), who specialise in making live, generative, code-based art in the form of large-scale installations, music and performance. In 3.24, they tackle “synaesthetic perceptions of infinite space, silence and death.”

A cavernous empty space, like multiple coalesced parking lots, pulsates between complete darkness and mixed, strobing patterns of flooding red and white lights. An ominous soundscape is interspersed with deafening silence, designed to evoke tension, alongside feelings of confrontation, randomness and the shifting absence of control.

“Music – or more widely, sound – is often a key element of immersive art,” Czetwertynski states. “It is an act of deep presence, not something you just step back and observe. It requires a strong engagement.” Sensitivity to how sound both builds and influences space is baked into The Beams’ history and purpose. The curator continues: “The auditory and visual aspects combine to create deep hooks for our minds and bodies to truly make ourselves present in the work.” 3.24 conjures the visceral experience of being crushed between bodies in the back of a concert, limbs thrumming with the feeling of sensory explosion and mob psychology.

However, 404.zero manipulate the theatrical nature and spatial experience of club spaces by rejigging the multisensory environment in unexpected directions. There is randomisation to patterns of movement; light and volume are altered arbitrarily; bodies become isolated from one another. The twin vehicles of art and technology culminate in a feeling of primal skittishness. The body cannot merely observe this space; its very relationship is metamorphosised.

Similarly, Matthew Schreiber’s Banshee (2023) demands direct interaction. The multidisciplinary artist is renowned for large-scale light sculptures, and this latest project consists of hundreds of red lasers that produce “geometric patterns that change as viewers move within.” The sculpture fills and twists in the room like an undulating muscle or strand of DNA, structured after Schreiber measured the room’s volume and divided it into symmetrical segments. Visitors walk into the installation, creating a productive tension between their bodies’ movements and the work’s static nature. The space is continuously made anew, repositioned by the audience. The effect is humorously reminiscent of a cat chasing a laser pointer. Equally, something curious and animalistic is teased from the human body and consciousness in Banshee, as individuals dive through and between ribs of bright light.

Site-specificity is key to many of the works in Thin Air, and to The Beams itself, as well as Broadwick Live’s larger vision. They repurpose old, abandoned and unused spaces, transforming them into vehicles for new, reinvigorated forms of human experience. “For me, curation starts with the space. What does it want? What pieces will create a conversation with the environment?” Czetwertynski says. “One has to fully understand what the space allows. It isn’t a white cube.”

Acknowledging the physicality of the exhibition is an important distinction in site-specific work that moves away from traditional forms of curation within a museum or gallery setting. Installations are customised to the contours of the venue, rather than transcribing existing artwork to a new location. This process can be compared to the creation of land art, in which “adaptations have to be made for the works to enter into this dialogue with the existing space.”

Technology is often instrumental in bridging the body and its surroundings, offering a more accessible and experiential way to produce, curate and exhibit art. This notion first drove the New Media Art movement in the 1960s-1970s, coinciding with the development of video art and other forms of electronic media. The evolution of personal computers and the emergence of the internet, widely attributed to 1 January 1983, further expanded the form, allowing artists to experiment with interactivity in the face of a hyperconnected world.

Pioneers of New Media art include Korean-American artist Nam June Paik (1932-2006), whose groundbreaking work in performance and technology-based art earned him the title “father of video art,” and text-based installation artist Jenny Holzer (b. 1950), has been making work for five decades. Recently, contemporary figures have built on developments in technology. Mexican-Canadian electronic artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer (b. 1967), for example, or Refik Anadol (b. 1985), whose 2022 work at MoMA, New York, transformed over 200,000 artworks into mesmerising digital installations.

How individuals produce and consume art continues to transform more rapidly than ever before, with the release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT4 in March 2023. It cemented the potential dominance of artificial intelligence in society. The world’s first AI-generated art gallery, Dead End Gallery, opened in Amsterdam this spring, while an image of Pope Francis in a cloud-sized, Balenciaga-esque puffer jacket, made on the AI generator Midjourney, went viral, prompting major concerns and debate on discerning image veracity in the media.

In Thin Air, these developments are not the focus but an ancillary and integral material in which both the artists and space function. It begs the question: “Is this the future of contemporary art and if so what comes next?” Czetwertynski enthuses: “These works aren’t ‘about’ the technology they use, they are about perception and emotion. Each is the creation of a fleeting reality that contains ideas and emotional landscapes to be felt and kept with you for further exploration.”

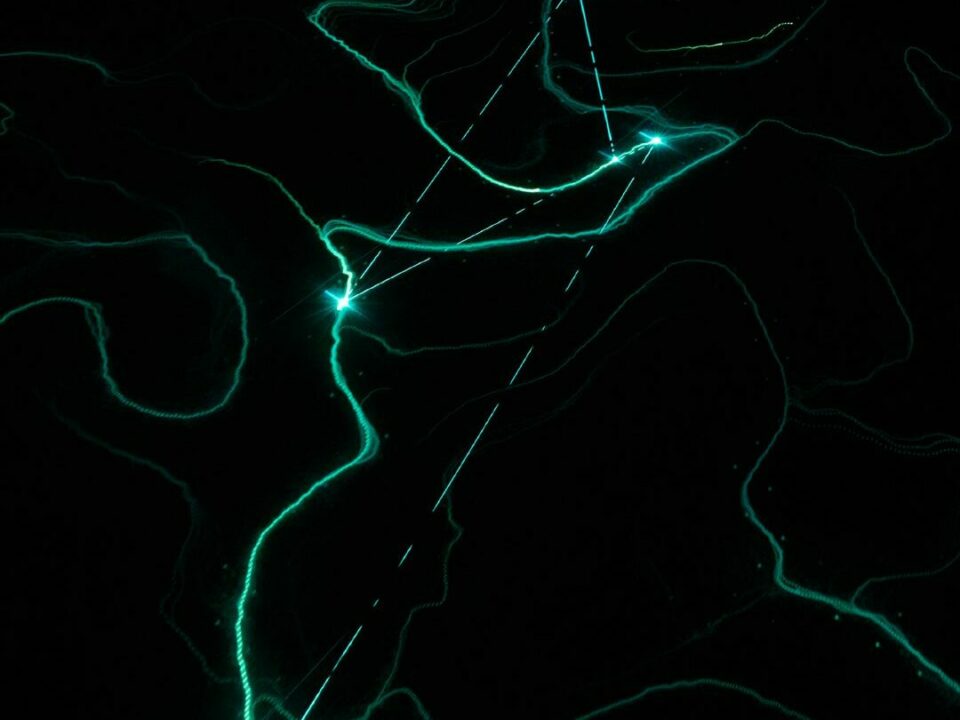

For example, digital artist Robert Henke’s Phosphor (2017) installation depicts the topography of a virtual mountain range. Focused rays of ultraviolet light, like little droplets of water, paint “temporary landscapes” on a layer of phosphorus dust. Henke developed the work’s software processes using Benoît Mandelbrot’s fractal geometry, early algorithmic art and contemporary big data models. There is a heavy technological influence, but at its heart, the work is about nature: geography and land, the mathematics of its ever-changing rhythms – the image we see on display is never the same again – and the connections between us all.

Commercial immersive art experiences have also become more popular, providing useful visual fodder for Instagramorientated audiences. The three-year run of Yayoi Kusama’s (b. 1929) Chandelier of Grief and Infinity Mirror Rooms at the Tate Modern have been a significant success, with various extensions and over 390,000 visitors. However, there is a risk of devaluing the meaning and narrative behind the work because of documenting the experience of it, with thousands flocking to share their snapshots on sites like Instagram.

The history and life of canonical artists and their careers are also being explored through immersion. The travelling Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience, in London, for example, attempts to use the digital realm and technology to preserve and revive art history in an accessible way. Meaning is injected through extensive brochures, QR codes and wall texts at every turn. Exhibitions like Thin Air, then, use a similar model in a more avant-garde and cutting-edge way; one that’s less focused on art history but more on art’s future.

Immersive installations are a reaction to the passivity of consuming art online and to the despair of doomscrolling. Czetwertynski suggests: “Too often we are considered passive actors in both art and life.” Spaces that continue to find new uses are at the centre of reconciling this agency, offering an active state of being that exists only with the help of media.

Thin Air

The Beams, London | Until 4 June

Words: Vamika Sinha

Image credits:

1. Robert Henke, Phosphor (2017). Photo: Sandra Ciampone.

2. 404.Zero, 3.24, (2023). Photo: Jesse Hunniford.

3. Kimchi and Chips, Light Barrier 2. Photo: Hanneke Wetzer.

4.S E T U P, BORDERS, (2023). Photo: Dmitry Chuntul.

5. Robert Henke, Phosphor, (2017). Photo: Sandra Ciampone.