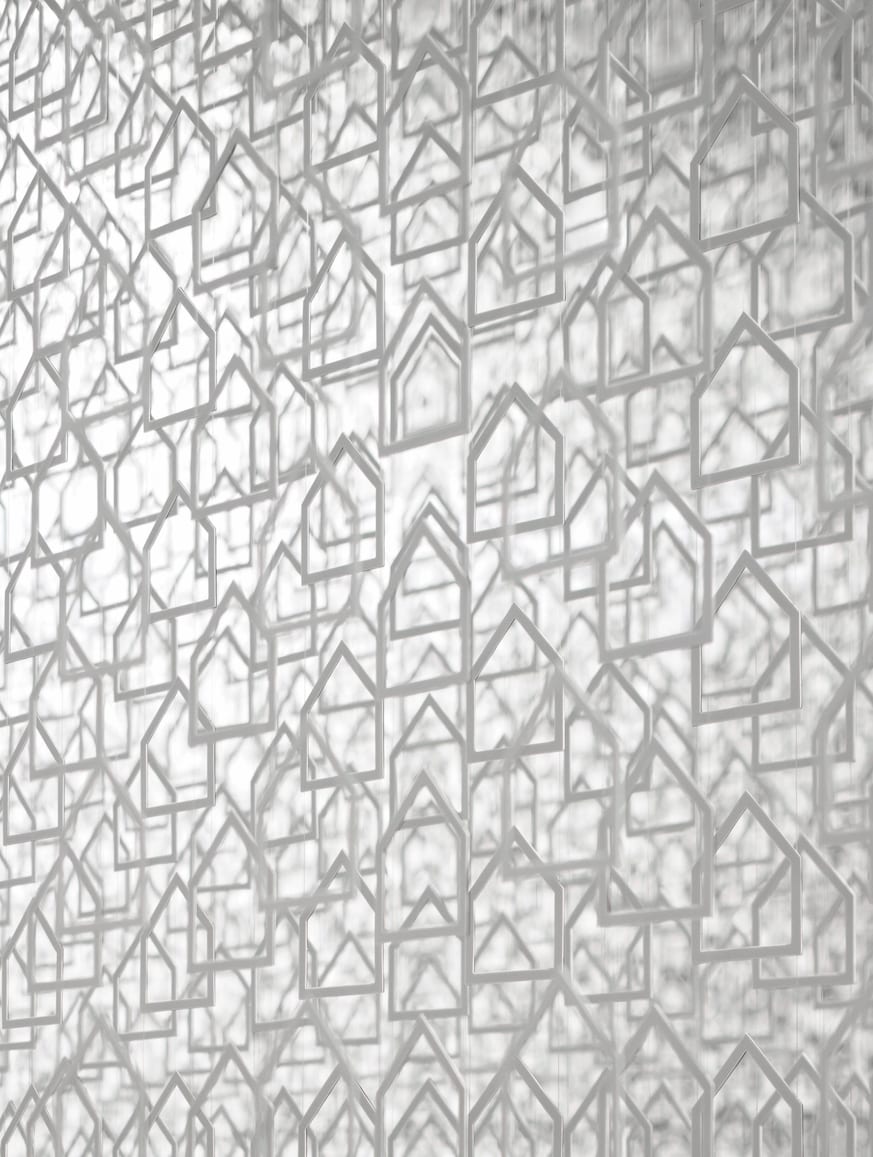

When the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, planned to stage a major exhibition of work by MC Escher in 2018, the cutting-edge Japanese design studio Nendo, with its pared-back but playful aesthetic, proved the perfect match for the Dutch graphic artist, known for mathematical tricks of the eye. However, the resulting collaboration, titled Escher X nendo | Between Two Worlds, went far beyond what the cura- tors had imagined. Nendo’s founder Oki Sato (b. 1977) took the simple form of a house and repeated it in myriad ways.

It was there when visitors entered, a dramatic interlocking pattern on monochrome wallpaper. It followed in the shape of a tunnel through which audiences moved from one sec- tion of the show to another, and a seating area from which to contemplate artworks on the walls. Other houses existed as fragmented black frames, which, only at certain angles, appeared to merge into a whole. Finally, a chandelier made of 55,000 tiny houses threw geometric shadows into every edge of the room, expanding the definition of the gallery.

“Sato understood from the outset that a ‘collaboration’ with MC Escher could allow a move outward – beyond the paper and the frame, beyond the wall and the floor – to manifest the thematic concerns and inspirations encountered within Escher’s work – sensorial, spatial and architectural,” writes NGV’s director, Tony Ellwood, in the foreword to a new monograph of the studio’s work since 2016, published by Phaidon. “Sato looped iconography and spatial experience in order to subtly question traditional notions of the relation- ship between art and design.”

At a time when many artworks are visible in digital reproduction at a mere click, Nendo’s approach to exhibition design asserts the preeminence of the gallery or museum as a site for unique physical encounters. Nendo’s relationship with NGV dates back to 2016, when Ellwood came across the studio’s installation 50 Manga Chairs at Friedman Benda, New York, and snapped up all 50 for the gallery’s collection. With a mirrored finish, each Manga chair was inspired by graphic elements taken from the iconic Japanese comics, from speech bubbles to lines indicating characters’ movements, sweat and tears. Sato has described Escher’s work as residing somewhere “between the possible and the impossible” and the same could be said of these chairs. Like optical illusions, the pieces toy with per- spectives, conflate dimensions and subvert our preconcep- tions about how objects or materials behave.

This, in turn, informs a number of the studio’s other designs. In the installation Into Marble, produced for Marsotto Edizio- ni during 2018 Milan Design Week, marble appears like a liquid substance into which tables seem to dissolve. Another collection of chairs, Watercolour, takes its cue from painting. The metal chairs have been painted matte white then daubed with blue ink; their surface recalls the texture of paper, which has been cut and folded – like an expansive blank page.

Oki Sato founded Nendo in 2002 when he was just 25 – fresh from a degree in architecture at Waseda University. Based between Tokyo and Milan, Nendo has since then established a reputation as a multi-award-winning, ground- breaking, global design studio, with a prodigious, multidis- ciplinary output that ranges from furniture to retail spaces, branding, stationary, toys, a portable toilet, pet accessories, multi-way zippers, cheesecakes, vases, in-flight tableware for Japan Airlines, rugby team uniforms, keys and jewellery. The roughly 30-strong team works on several hundred de- signs at once – and Sato is personally involved in each one.

“The more ideas I think of, the more ideas I come up with. It is like breathing or eating,” he told Dezeen in 2015. “If I focus on only one or two projects, I guess I can only think about one or two projects. When I start thinking about work- ing on close to 400 projects, it relaxes me. It’s like a top; when it is spinning very fast it is stable and when it starts to spin slowly it starts to get wobbly.” The dazzling breadth of Sato’s work is revealed in the Phaidon publication. Nearly 500 pages lay bare the evolution of the studio’s practice, steered by Sato’s consistently trailblazing vision.

Ironically perhaps, given its wildly prolific output, Nen- do’s approach is minimalist at its core, tending towards clean, continuous forms constructed using few materi- als with a restricted colour palette of black and white, or calming hues such as greys, blues and pastels. Japanese minimalism advocates using only what is essential, favouring unfussy shapes, neutral tones and unadorned, natural materials that give light and space room to breathe.

Its principles are embodied in the concepts of “Wabi- sabi” and “Ma” – with roots in Zen and Mahayana Bud- dhism, Wabi-sabi recognises impermanence and imperfec- tion. Aesthetically, this means that simplicity, asymmetry, weathering and careful craftsmanship are prized. “Ma”, meanwhile, translates as “gap” or “pause”, and emphasises the importance of negative space. In Nendo’s work, these tenets can be seen in a form of subtraction; often the crux of the project is found in what’s removed, reduced or sliced out. Meji, for example, reimagines a bulky umbrella stand as a sleek grey cuboid structure, with subtle grooves that are only noticeable when used to insert an umbrella.

By reducing visual and spatial clutter, minimalism en- courages us to slow down and to focus on the minutiae: the rich complexity of life that might otherwise go unnoticed, whether it’s shadows dancing across a wall, or the view of falling leaves through a window. Minimalism grounds us in the physicality of the present, and, the argument goes, opens a space for our minds to fill up with imagination rather than being overloaded with information. That’s why Montessori educational children’s toys are simple and functional. It’s why Steve Jobs had a wardrobe full of hun- dreds of identical black turtlenecks – courtesy of Japanese fashion designer Issey Miyake, whom Sato cites as an abid- ing influence. The repetition of this uniform, Jobs believed, was liberating. By eliminating the choice of what to wear, he could direct limited time and energy elsewhere.

Sato agrees: “I don’t think that special moments create special ideas,” he told Domus in an interview during Salone del Mobile 2019. “I think that boring moments do: the everyday routine – like waking up, brushing your teeth – it really resets my mind, I can stay blank and be cen- tred. When you work on so many projects you might lose yourself. By doing the same everyday things I am able to become zero again and have a fresh mind always.”

These ideas have become incredibly popular in recent years, not only as design choices but as lifestyles. Perhaps it’s a reaction to capitalist excesses, rampant consumerism, digital dissemination, economic crises and climate catas- trophe. The simple life holds great appeal. A rising appetite for stripped-back aesthetics underpins much of 21st century lifestyle trends – from Scandi Hygge practices to digital detoxes; the market in vintage mid-century modern furniture, to the tiny house movement. Decluttering guru Marie Kondo, whose 2014 book, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organ- izing, urges us to “keep only those things that speak to the heart, and discard items that no longer spark joy” – a contemporary take on that William Morris adage “have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.” Indeed, after selling more than 11 million copies of her book, Kondo launched the Netflix reality show Tidying Up with Marie Kondo, which is now available to view in nearly 200 countries over the world.

The idea of “joy” is important here, because, without it, minimalism can sound a tad austere – another self-help stick with which to beat ourselves. Nendo takes its name from the Japanese word for “modelling clay” or “Play-Doh” and there’s a ludic, sometimes almost mischievous spirit that runs throughout their designs, often tapping into tradition or nostalgia around Japanese culture. The Coen Car is a fleet of mobile children’s playground equipment which, though in trademark monochrome, draws on the visual trend of Kawaii or “cuteness” that has become a mainstay of the “Cool Japan” brand, whilst Grid-Bonsai is a 3D- printed bonsai tree that can be trimmed to a shape of the individual’s liking. Here, function and fun go hand-in-hand.

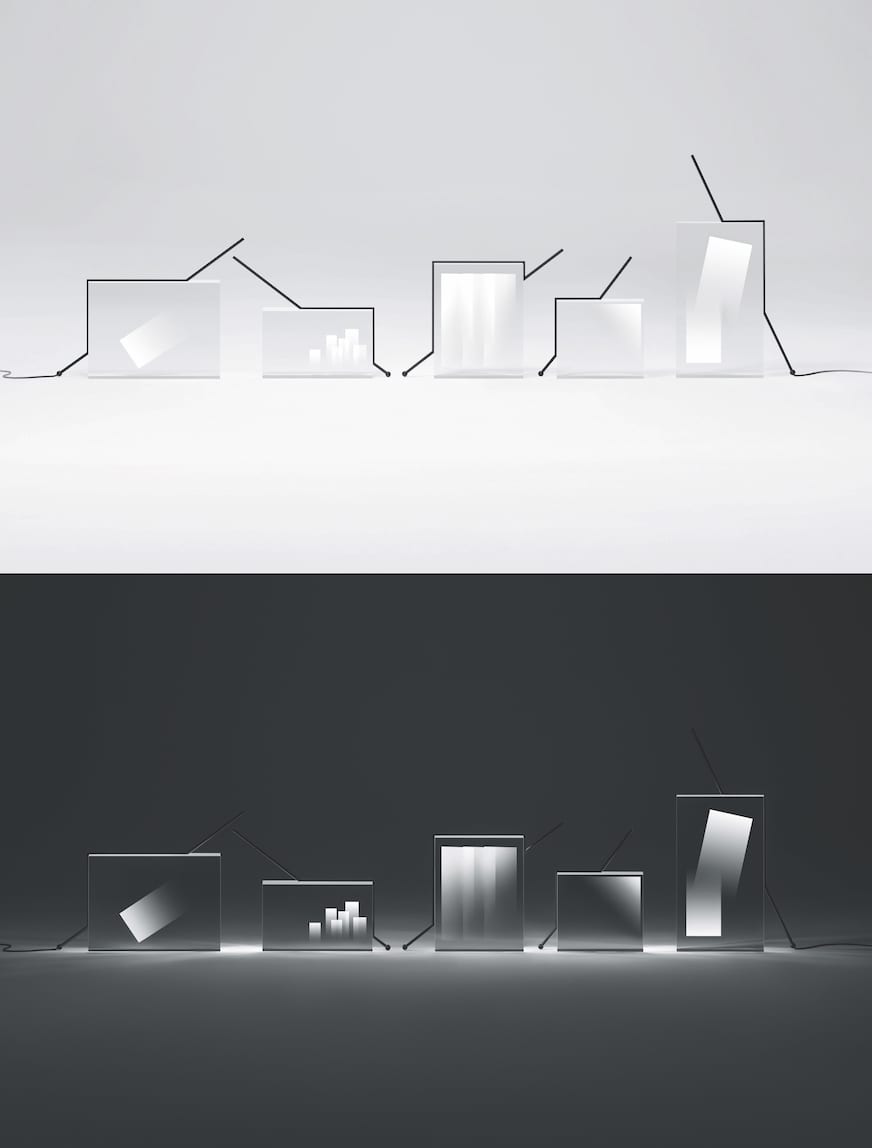

Also like Play-Doh, Nendo’s projects are often intended to be flexible, allowing users to reshape or adapt pieces to their own unique tastes or changing needs – from modular sofas to whiteboards that double up as office dividers, as well as folding phones, sliceable trophies and a magnetic desk lamp that can be broken down into its constituent parts and recomposed in multiple ways. If any one thing can define contemporary culture, it’s heterogeneity. Individuals want to assert their own identities, customise items and carve out a world that responds to and works for them.

Where once British teens gathered around the TV on a Thursday evening to watch Top of the Pops and compare notes the next day, they now discover new music through the algorithms of Spotify recommendations. In Nendo’s world, this translates as giving agency to those who interact with their projects. In their curation for Inspiration or Information? A 2018 exhibition of traditional Japanese art at Tokyo’s Suntory Museum of Art, individuals were offered the choice of two routes through, one of which showed the art- works together with contextual details, the other left them to have a purely intuitive, emotional response.

Ultimately, this is what “good design” is about – not things or even ideas, but people. Tenri Station Plaza CoFu- Fun is an early example of everything that makes Nendo distinctive. A multi-use development containing bike hire, a cafe, a stage, meeting spaces and more, its unembellished white, saucer-like curved structures are a nod to the ancient tombs or “cofun” of Tenri, a city in the Nara Basin. At every turn are flights of steps. Or perhaps they’re benches. Or shelves. The point is they’re all of these things and none of them. They’re design tinder. Really, what Nendo produces isn’t objects and buildings, rather personal experiences: opportunities to pause and wonder at what’s hidden in the everyday. After all, as MC Escher once put it, he, she or they “who wonders, discovers that this, in itself, is wonder.”

Words

Rachel Segal Hamilton

Nendo: 2016-2020 is published by Phaidon. phaidon.com.

Image Credits:

1. Flow, 2017. © nendo

2. Gaku, Flos, 2017. © nendo

3. Light-Fragments, Ymer&Malta and the Noguchi Museum, Queens, New York, 2018. Picture credit: Kenichi Sonehara .

4. Flow, 2017. © nendo

5. Breeze of Light, Daikin, 2019 Picture credit: Takumi Ota.

6. Escher X nendo / Between Two Worlds, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2018. Exhibition featuring the work of Dutch graphic artist MC Escher. Picture credit: Takumi Ota