“Communication, with its entire media, could really be at the service of the humanity,” stated Oliviero Toscani (b. 1942) during a speech at ADC NY and D&AD London Arts Directors Club in 2015. The Italian artist is known for pushing against the mainstream, emphasising the power of photography to deliver impactful messages. In the 1980s and 1990s, for example, collaborations with Vogue, Chanel and, most notably, United Colors of Benetton, brought social issues to the forefront of major campaigns, countering advertisements that prioritised consumerism and unrealistic beauty ideals. Now, Toscani’s first solo show in London, TOSCANI CHEZ MAZZOLENI, raises crucial questions about the purpose of photography in a world shaped by war, social divide and economic turmoil.

Mazzoleni Art delves into the artist’s back catalogue to present historic and new shots in radical ways, including printing on microcement. Bold portraits are found alongside abstract landscapes, drawing attention to ongoing debates on integration, religion and sexuality. A complementary presentation at the Embassy of Italy in London also showcases the artist’s ongoing project, Razza Umana (Human Race) (2007-present). Curated images navigate expressions of the human condition, expanding on themes of representation and diversity. Ahead of TOSCANI CHEZ MAZZOLENI, the photographer speaks to Aesthetica about the evolution of his practice as well as revisiting his archive for the exhibition.

A: Your photography spans advertising, architectural, documentary and fashion. How would you define your practice? How has it evolved over your career?

OT: I don’t define myself as a photographer, whether that be fashion or advertising. I am not a documentarist. I don’t work for art directors or advertising agencies. I take the pictures that I feel I have to take. Photography is just a technical definition of how you do a job. I am an author. I work in modern communication and use photography to express myself.

A: In the 1980s, you began collaborating with United Colors of Benetton on their visual identity. Glossy, idealistic campaigns were replaced with socially-conscious photographs, shot against bright white backdrops. Why did you decide to take this approach?

OT: What I do is driven by my own vision and ideas. It is not about breaking the rules for me. Fashion is a certain way, I didn’t choose it to be like that. I worked a lot for British magazines in the 1970s and 1980s. They were calling me because of my way of thinking about fashion. I don’t care about selling clothes with my images, that’s not my job. I worked in fashion when it was important in modern society. Right now, its relevance is different than before. For example, when I started taking pictures, everyone was doing reportages, mainly about wars. Instead, I decided to photograph Mary Quant making the mini skirt. I thought that this was much more politically, socially and ethically important than taking pictures of an event everyone already knew about. It was already on television. There are events that don’t seem important to begin with, but they are. You have to be aware at what kind of level you want to be the witness of your time.

A: You’re an advocate for equality through your work, championing diverse casting in an industry that has historically been associated with promoting a particular body type. What inspired this commitment?

OT: All of this belongs to my way of thinking. I didn’t choose my models from agencies. I put together an office called Sauvage Casting, picking and photographing people we encountered on the street. This was a lot more interesting. This has been my whole approach to fashion. I remember I took the first picture for i-D with Terry Jones, photographing people from the street. The first issue of i-D. Just look at the magazine. My work is about “research and repeat:” you have to be an honest witness of your time, responding to what is going on around you. I would choose young people who had the “face of the moment.” They’re new. I don’t like the ultra-banality of commercial beauty. There’s nothing more boring than standard, accepted beauty. I was looking for different expressions of self and ways of being in different music, fashion and places.

A: You are a founding professor of Mendrisio Academy of Architecture, Switzerland – a renowned school that links architecture, urban studies and visual communication. How has this academic work influenced your practice?

OT: That’s my education. I studied in Zurich with a great Bauhaus teacher. My aesthetical and compositional education in photography was very solid and specialised. I’ve followed this style all of my life. In 1993, we founded the Mendrisio Academy of Architecture. I did teach there for a couple of years, I got bored, I left. It was a good experience.

A: The exhibition spans your whole career. What is it like seeing these works displayed together?

OT: I am more focused on the present than the past. I don’t like archives very much. Luckily there are people who look through my files. I let trusted people around me to pick my works, and decide what’s best for the show. For me, that’s all past. I “look back in anger.”

A: Your photographs for this exhibition – such as Grande Cretto – are printed on slabs of concrete. Why did you select this printing technique?

OT: Printing on concrete is a decision, a test. I thought it was interesting to print on concrete, especially the Cretto, as the original Land Art work in Gibellina, Sicily, is made of concrete. I have many photos printed on concrete in my house. I find the material very nice. I don’t think pictures should be printed to be hung on the wall. Photography is made to be published in print media, or posters in the street. Photography is not meant to stay there forever. It is information, communication. Today, images are the most important elements surrounding us. We live with them. It’s impossible to imagine a modern world without images. Everything we know about – people, places – is because we see pictures of them. I don’t think photography is meant to be hung on a wall, but it’s okay too to have it there. I am very pleased to come to London for the opening of the exhibition at Mazzoleni.

TOSCANI CHEZ MAZZOLENI

Mazzoleni, London – Torino, London | 26 April – 4 June 2023

Private View: 25 April, 18.00-20.00

Interviewer: Saffron Ward

Image Credits:

1. Oliviero Toscani 1942 San Francesco, (2019). Giclée print on microcement on okumè wood panel 57 x 100 cm 22 1/2 x 39 3/8 in © Oliviero Toscani. Courtesy the Artist, Mazzoleni, London – Torino

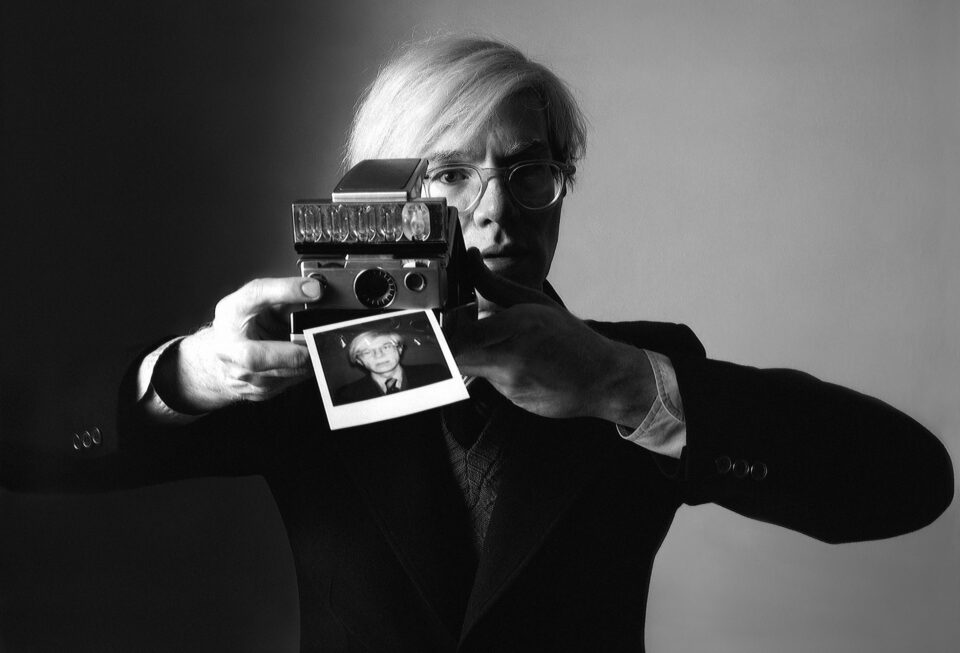

2. Oliviero Toscani 1942 Andy Warhol, (1975). Giclée print on microcement on okumè wood panel 68 x 100 cm 26 3/4 x 39 3/8 in © Oliviero Toscani. Courtesy the Artist, Mazzoleni, London – Torino

3. Oliviero Toscani 1942 Cretto di Burri, (2018). Giclée print on microcement on okumè wood panel 83 x 110 cm 32 5/8 x 43 1/4 in © Oliviero Toscani. Courtesy the Artist, Mazzoleni, London – Torino