Around the time that the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) was established, John Baldessari, the school’s chair of “Post-Studio” practice, jotted down a set of notes outlining his ideal art college: “A watering hole, a flow of artists. Artists as ordinary people. Have artists as models. Create an environment where art can happen.”

Adapting his phrasing, Where Art Might Happen: The Early Years of CalArts offers a bountiful history of the school’s formative decade, a companion to the eponymous 2019 exhibition at the Kestner Gesellschaft, Hannover. This volume partly aims to redress imbalances in previous critical coverage of CalArts, highlighting work by lesser-known figures and focusing on the legendary but long understudied Feminist Art Program.

The story of the school’s foundation is a bizarre one, bringing together California’s twin worlds of movie-industry artifice and post-hippie radicalism. In 1961, Walt Disney brokered the merger of a music conservatory and an art college to create what he hoped would become a kind of gated community of arts-and-crafts creativity, replete with shops, restaurants and galleries. The 1964 premiere of Mary Poppins was used to outline his vision, in the form of the short film The CalArts Story. But the first academic semester would not commence until 1970, four years after Disney’s death, by which point his ideas had been adapted to an almost comical degree. As Janet Sarbanes notes in one of several essays included in this book, the school was thus forged “with an apparent schism at its heart: dreamed up by [a] progenitor of American cultural capitalism, it pulled its first faculty from the politically and aesthetically revolutionary ranks of the East Coast avant-garde.”

That faculty included figures from the post-Fluxus and conceptual art scenes such as Allan Kaprow and John Baldessari—and though the pedagogical model was rooted in practices established at the Bauhaus and elsewhere, it was nonetheless trailblazing. As Philipp Kaiser and Christina Végh note in their introduction, “with respect to teaching, the educational elements established at CalArts—such as the Visiting Artists Programs, extensive critique among one another, study trips, and excursions, as well as, quite generally, a pluralistically oriented understanding of art—are now truisms of artistic training.” CalArts also did away with distinctions between teacher and pupil, focusing not on the nurturing of raw talent by learned elders but the collective development of critical-creative attitudes through spontaneous collaboration (in one of many interview snippets included in the text, composer Barry Shrader recalls scheduling a class to begin at midnight, giving a sense of the chaotic spirit about the place.)

The mood of early CalArts was embodied in a 1970 work of Kaprow’s, Publicity, which took the form of an anti-institutional team-building exercise for new cohorts. Heading off into the desert outside Los Angeles, groups of students would build rudimentary wooden structures whilst being filmed on handheld video recorders, the camera team then playing back the work on site as a spur – in Kaprow’s words – to “maybe new ideas, changes, reconstructions—more recordings”, “going on till sundown or till everyone’s tired.” As this sketch might suggest, much of what went on was ephemeral in form, hard to reduce to a catalogue of objects or even conceptual art-style documentation.

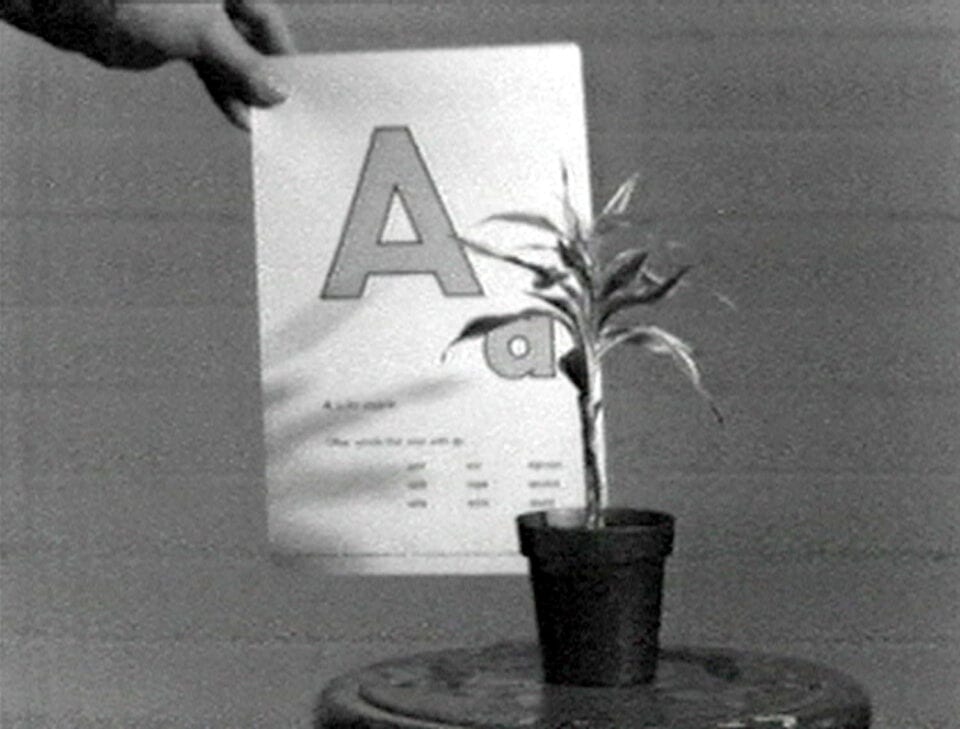

Of particular importance to the creative networks that emerged over the next few years were Baldessari’s Post-Studio course and Judy Chicago’s Feminist Art Program, both given due attention in this volume. Baldessari’s Post-Studio classes sought to nurture an artistic attitude or stance that could be activated in any context, without access to standard art materials. His teaching prompts read like event scores: one 109-point list contains such instructional gems as “Defenestrate objects. Photo them in mid-air;” “What kind of art can be done with real animals?” The performative quality of such pieces is no accident. As Thomas Lawlor notes in his institutional history, Baldessari also “blurred the boundaries between art making and teaching.”

Chicago’s Feminist Art Program, sidelined in some previous presentations of CalArts work and theory, was established by Chicago at Fresno State College in 1970, but was transported to CalArts the following year with the help of Miriam Schapiro. Starting from the premise that women’s experiences and views of the world were routinely erased from the canon of art, Chicago and Schapiro used “consciousness-raising” group activities to unfetter women’s creative perspectives. Some of the work emerging from these classes, such as Mira Schor’s Class Assignment: Self-Image, is reprinted, alongside an essay on the influence of FAP pedagogy on Kaprow’s work.

Chicago and Schapiro’s approach bore fruit across a range of media, including work exploring women’s societal roles and expectations, their rights and media representation, and their relationships with their bodies. The iconic early achievement of the FAP was the creation of the so-called Womanhouse, an abandoned dwelling converted by 27 artists into an evolving creative environment, opened to the public for a period in February 1972. The work presented in this space included sculptural pieces integrated with the architecture like Kathy Huberland’s The Bridal Staircase, with its sacrificial white-robed mannequin, and performances such as Faith Wilding’s Waiting, a description of a woman’s life from birth to death as an ongoing process of waiting.

The events and processes that unfolded at CalArts in the early years did not lend themselves to easy preservation. As ex-student Simone Forti notes, “we assumed that we would influence people in the coming generations. That’s how the work was being retained.” This book combines facsimiles and installation shots with an array of weirder archival material – such as Ann Noel’s beautiful “Visual Diaries” – alongside interview transcripts and historical and conceptual texts to offer a lifelike impression of a fruitful but chaotic creative scene, ensuring that the liberatory message of CalArts can continue to resonate today.

Where Art Might Happen: The Early Years of CalArts is published by Prestel. Find out more here.

Words: Greg Thomas

Image Credits:

1. Judy Chicago, “Orange Atmosphere.” Live performance. Performed at Brookside Park, Pasadena, California, 1969. Photography by Through the Flower Archives. © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco.

2. Carrie Mae Weems Mom, Family Pictures and Stories, 1981-82. B/W Photgraphy. 23,66 × 35,98 in. ©Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy the artist; and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

3. John Baldessari, Teaching a Plant the Alphabet, 1972. Video still.