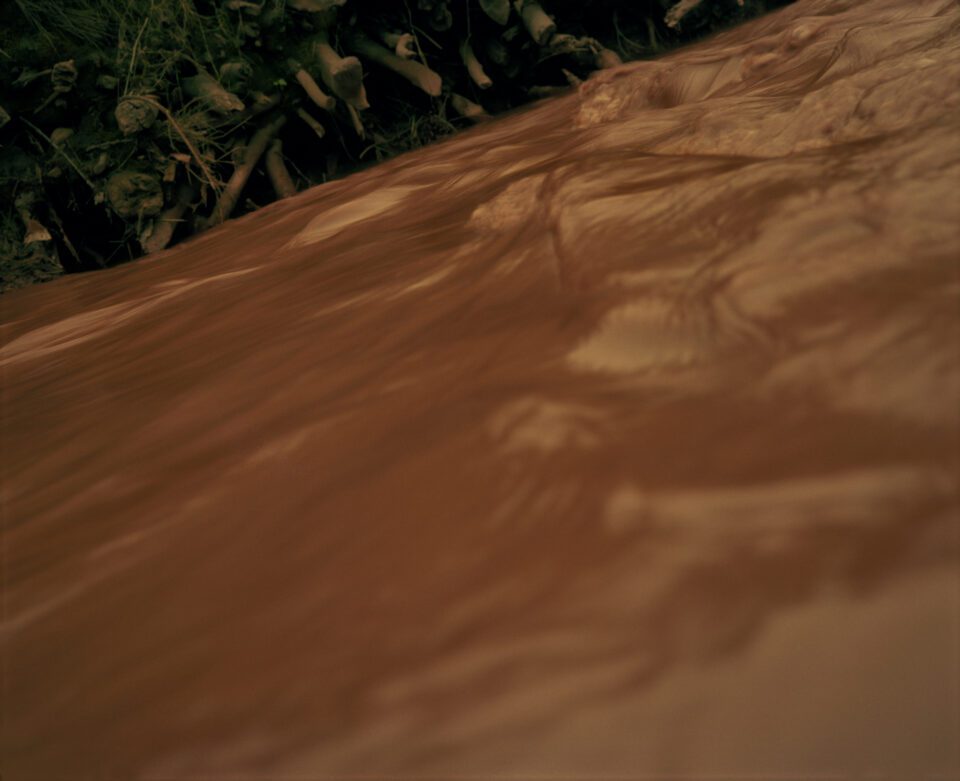

“It is the purpose of this book to describe and evoke something of the distinct, rich history and culture of the valley.” These are the words of Jem Southam (b. 1950) in The Red River. He has explored the landscape of Cornwall and its history of tin mining through the lens for more than 40 years. His images document a world in flux, with the closure of heavy industry and the emergence of modern technologies. The fingerprints of human activity are everywhere in the images, and yet there continues to be a rugged, unspoiled feeling too, which feels like an echo of the ancient, mythical lands that are so often referenced in his work. Now, decades after the collection were first published, Southam revisits the images in a new edition. We spoke to him about how the locations have changes in the past decades, the legacy of his work and why he wanted to return to the series.

A: Tell us about how you got into working behind the lens – where did it all begin?

JS: When I was at school as a teenager, a friend and I found an old musty darkroom in a shed, refurbished it and set off. My father gave me his old 35mm Ilford Sportsman rangefinder camera for my fifteenth birthday. We had no idea what we were doing, no tuition or guidance. The first box of developer I bought produced very dense grainy negatives, it took over a year for me to realise that it was a paper developer, I still like the results though! We had a great time and somehow I managed to produce some photographs which got me a place to study photography in London.

A: You first stumbled across the stream in these images whilst walking your dog, and returned to photograph the site for six years before the series was published. What is it about the location that kept drawing you back?

JS: A few years earlier I was discussing ideas with a friend, Paul Graham, in Bristol where we worked and shared a darkroom. The notion of following some sort of line on a map came up. Paul set off to make the work called A1, following the length of an important and historic road from London right up to Edinburgh. As soon as I came across that thin red stream in Cornwall, where I had just moved to start my teaching career, I knew I had found my subject and that I would make a work following it from the source to the sea. In the early 1980s we had no artistic role models in Britain who were photographing in colour, so making a work was a challenge and adventure. I had no idea what sort of pictures I would take or the concerns and issues it would encompass. It took that long to realise and resolve these questions.

A: Could you tell us a bit about the history of the area? How has tin mining shaped the landscape?

JS: Tin and copper have been mined in the West of Cornwall for several thousand years, the Phoenicians even sought out their supplies of these ores. The early mining usually involved following a seam in from a cliff face, it was not until the invention of gunpowder that deep mining could be undertaken. The area around Camborne where I was living was a centre of such mining and at one point it was thought to be the most industrialised landscape on earth. The space was still riddled with mines, shafts, adits and piles of waste rock when I began photographing, in many places it was still a smashed wasteland.

A: How has the site changed since you first documented it?

JS: It was strange that almost as soon as I had first shown the resolved work, in November 1987, everything began to change. South Crofty, the last surviving tin mine in Cornwall, closed the month my exhibition opened and gradually the stream cleared. The beach at Godrevy was dug up to create an underground water treatment plant. Satellite dishes appeared on many houses, domestic gardens radically altered with the coming of new Garden Centres, the Agricultural Research Station at Reskadinnick was shut down – on so many levels it was no longer what I photographed and my pictures conveyed to me an archaic land.

A: You originally intended on creating work with a ‘topographic’ viewpoint but felt dissatisfied with the detachment of the approach. Why did capturing the land, farm animals, tourism and legacy of mining feel like the right approach?

JS: I wished to describe something of the life and culture of the valley, its highly distinctive and historic nature, and also to make a more varied group of photographs than the rather straightforward topographic view from a prominent position. I also bought a smaller lighter camera, a Plaubel Makina, which allowed me to work in a much more fluid manner. These cameras were being used by many of us and radically altered the way in which we made pictures, opening up fresh possibilities.

A: The Red River was published in 1989. Why did now feel like the right time to revisit the project?

JS: it is 40 years since I made the work and waves of change have swept the photographic medium and its uses along, and apparently for some The Red River is significant, is still relevant, and they wish to be able to access the work. In November of this year Tate Britain are presenting an exhibition which looks at what was happening in British photography through the 1980s. Looking back it was an extraordinary decade and this exhibition may hopefully help galvanise more interest in bodies of work made during that time, some of which have had lasting legacies. When I travel and meet my peers the subject of The Red River often comes up and many younger photographers who have not been able to acquire a copy of the original have asked me if I have one I could sell them.

A: The volume includes excerpts from a variety of literary sources, including D. M. Thomas, Beowulf and John Milton’s Paradise Lost. How does mythology and literature influence your practice?

JS: The Red River was a great learning experience for me. I came to realise as I worked that landscapes are both physical constructs – an infinitely complex blending of natural and human forces – and also profoundly cultural constructs. As each of our lives unfold we learn about the world from a stream of stories and pictures, lessons and experiences, which give shape and influence our understanding of the Earth. The Red River was an attempt to both describe a place and a culture, and at the same time, to explore how some elements of these stories survive and surface in our imaginations.

A: The work is divided into seven parts – they reflect on a succession of myths concerning perceptions of the landscape. Could you tell us a bit more about this? How did you decide on these names?

JS: The titles of each section are the names of the places photographed, as the pictures follow the stream from its source to the sea. The idea of the seven sections evolved through the early stages of it’s making. They are roughly geographic and the myths are draw on narratives which we all share, part of our common heritage.

A: Who – or what – are your biggest inspirations?

JS: When studying in London between 1969 and 1972 I saw just two photography exhibitions, one by Paul Strand and one by Bill Brandt. How fortunate, great role models! It may sound strange to say this though but I think the biggest inspirations in my photographic life have been many of the students I have taught and worked with – the enthusiasm and excitement for the medium generated by a close group of people working together is remarkable, one learns so much as a teacher. Otherwise I draw on many influences, especially from literature and painting.

A: How do you view the role of art in documenting and preserving ever-changing landscapes?

JS: A simple question that lies at the heart of our shared love and fascination with the medium is ‘What can photography do?’ A still image can present an incredibly complex set of relationships and connections of materials manifest in front of a camera – in a way that I believe no other medium can manage. Two photographs of the same place, taken some time apart and presented next to one another, will provide a curious viewer with an indication of change and transformation. I have been standing at the same site on a riverbank near my home for nine years now, observing Winter dawns, and every morning the world is a different place, and with a camera I can notate something of that wonder.

A: If you could only show us one photograph from the book, which would it be, and why?

JS: Gosh that is a tough one. When I was working on the series of pictures I often looked at and thought about Bruegel’s Return of the Hunters which encompasses a view from the immediate foreground down through a valley, way out to the sea in the far distance. It tells a multitude of stories and I realised that while a painter can construct such voyage through a picture, I as a photographer would have to tell such a complex web of narratives in multiple pictures tightly structured together. So I see The Red River as an undivided whole. If there is one picture that I really cherish above others it may be the view of the two streams merging with one another. Not that it is a great picture but it is a picture that led to many subsequent ideas and bodies of work.

Jem Southam: The Red River is published by RRB Books: rrbphotobooks.com

Words: Emma Jacob and Jem Southam.

Image Credits:

Bolenowe Moor © Jem Southam.

Newton Moor Farm © Jem Southam.

Roseworthy Stream and Red River meet, Ponsbrittal © Jem Southam.

Fortescue Shaft, The Great Flat Lode © Jem Southam.

The Black Rock © Jem Southam.

Valley of the Barking Dogs, Brea Aditt © Jem Southam.