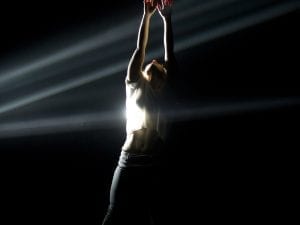

The London-based company explores how dance can bring emotion to science with its new piece 8 Minutes, showcased at Sadler’s Wells.

If a concise explanation of the similarities between dance and science is required, then choreographer Alexander Whitley offers a brilliantly simple one: “Essentially physics is the study of movement; of atoms on an incredibly small scale, or planets, on an enormous scale. Choreography also does this.” In Whitley’s new dance work, 8 Minutes, he ambitiously combines the two perspectives to explore the vast scale of planetary movement in an immersive performance.

Created in partnership with STFC RAL Space, an organisation that forms part of the Science and Technology Facilities Council at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in Oxfordshire, the show takes inspiration from the project the Solar Dynamics Observatory. The mission has been collecting visual data on the sun since 2010 and was created to help us understand its influence on our planet.

Whitley explains further: “They have a satellite orbiting the sun which is capturing high definition images of it every few minutes. We are now able to see in incredible detail, and continuous observation helps us understand a lot about the cycles of activity on it, which obviously, in turn, have an impact on our atmosphere and environment.” The Solar Dynamics Observatory is able to identify patterns that only became visible through the accumulation of data.

However, data as a static entity, as numbers, is very difficult to analyse, so the visualisation of it is an incredibly important step in its analysis. Increasingly this representation involves movement. A great example of this comes from Tekja, commissioned by the Science Museum to create a data-driven animation, Our Lives in Data, which gave meaning to the data contained within Oyster cards: their animation shows the patterns in the journeys that Londoners make across the city, which in turn offers important insight to programmers as to how people use the transport system.

Taking this concept even further, the development of virtual reality technology offers the opportunity for three dimensional visualisation. Viewing data in three dimensions physically can reveal even more previously unseen patterns.

This makes scientific investigation much like dance, of course. Whitley says: “One piece of data on its own is useless. It has to be compared and contrasted with other measurements so there’s something inherently dynamic in that. There are obvious parallels with dance and choreography. It’s really about the patterning and the sequencing of movement and the meaning that emerges through those patterns and those cycles of activity. I guess dance can help to interpret or give another reading of what that data might be.”

Whitley explains: “Both disciplines tend to suffer a bit from being inward-looking” and that “we can learn more about the world by seeing them [art and science] as one process of investigation, rather than drawing boundaries between them.” Art is great at elucidating some of the more complex ideas. Dr Hugh Mortimer, the lead scientist on the project agrees with this approach: “The processes that we use to look at the world are almost identical; however, the real difference comes in how we present our findings. The artist can bring that science to life, show meaning to people that are untrained and provide insight into the way that humans understand and interact with their surroundings.”

Although, as Whitley explains: “In dance and choreography there are a lot of rational, methodical processes that you go through to make the piece which are comparable to a lot of empirical practices.” It is really in the articulation of the emotional side of the science that dance, or art, excels. For Whitley, emotion is “one of the primary means of communication in dance.” This applies to the movement inherent in science too: anyone who has observed the Aurora Borealis or been awestruck by the night sky understands the personal and introspective impact that science can wield.

The difference is, as Dr Hugh Mortimer points out, simply how that emotion is explored. Whitley suggests that whereas in dance, feelings are one of the final products, in science they exist at the unobserved nascent beginnings of study: “There has to be inspiration in the first place to kickstart investigation.” Space is one of those areas of science that is particularly emotive. It’s an aspect of scientific study that seems to ignite the human imagination: 600 million people watched the first Moon landing on television in 1969.

Whitley has a theory about why space has such impact for a lot of people: “As you start to grapple with some of the really big ideas of the universe, it blows your mind. It challenges your ability to imagine. And I think when your imagination reaches those limits, it becomes a really moving thing.” It’s an area of science that is of personal interest to Whitley and he states: “I hope the piece encapsulates the many different ways in which we relate to and understand the sun.”

He talks about some of the more abstract theoretical understandings, drawing on the idea of electromagnetism for aspects of his choreography, and also speaks about the notion of human relationships to the star: “It determines the kind of rhythms we live by, the day / night cycle, and also the kind of deeper historical connection that we have to it through the way that the sun has been revered and worshipped and that kind of strong symbolical relationship we have to it as life-giver but also threat to our existence.”

The title of the piece, 8 Minutes, is a reference to the amount of time it takes for the sun’s light to reach the Earth. “The understanding of how ideas unfold over time is something I think about a lot. So it seemed appropriate to take a reference to time in order to tie the science and the dance together.”

Whitley collaborated with electroacoustic music innovator Daniel Wohl on the score and with BAFTA winning artist Tal Rosner on the visuals. “There was something in [Wohl’s] music that seemed to lend itself very well to this subject matter. It is kind of patient and ethereal at times. It seems almost to be existing on those kind of higher planes.” With Rosner it is “probably where the most literal representation of the subject matter will take place – a lot of the popular understanding of space is through the imagery.”

Whitley suggests that it’s inevitable that we will start to see art and science blend further: “Artists are increasingly turning to technology, not just as a means of being creative but as a means of engaging with the contemporary condition, which is so mediated. It’s important that practitioners grapple with and understand that as a way of attempting to reflect the modern world in the work they make.” It’s something that the Alexander Whitley Dance Company is already pioneering through their creative learning programme. Using kinaesthetic methods, they are developing another way of using movement to understand data – translating the patterns found in dance to explore the patterns found in science.

Bryony Byrne

8 Minutes

Sadler’s Wells, London. 27 – 28 June.