Sarah Sze (b. 1969) creates complex visualisations of the human world and the systems we use to measure it. In an introductory essay to her new book, the philosopher Bruno Latour recalls that when he first encountered Sze’s work in 2016, “I stayed for more than an hour in front of the artwork, silently taking it in.” This state of deep attentiveness is partly testament to the sheer volume of information conveyed by Sze’s three-dimensional constructions, which incorporate vast networks of objects and moving images.

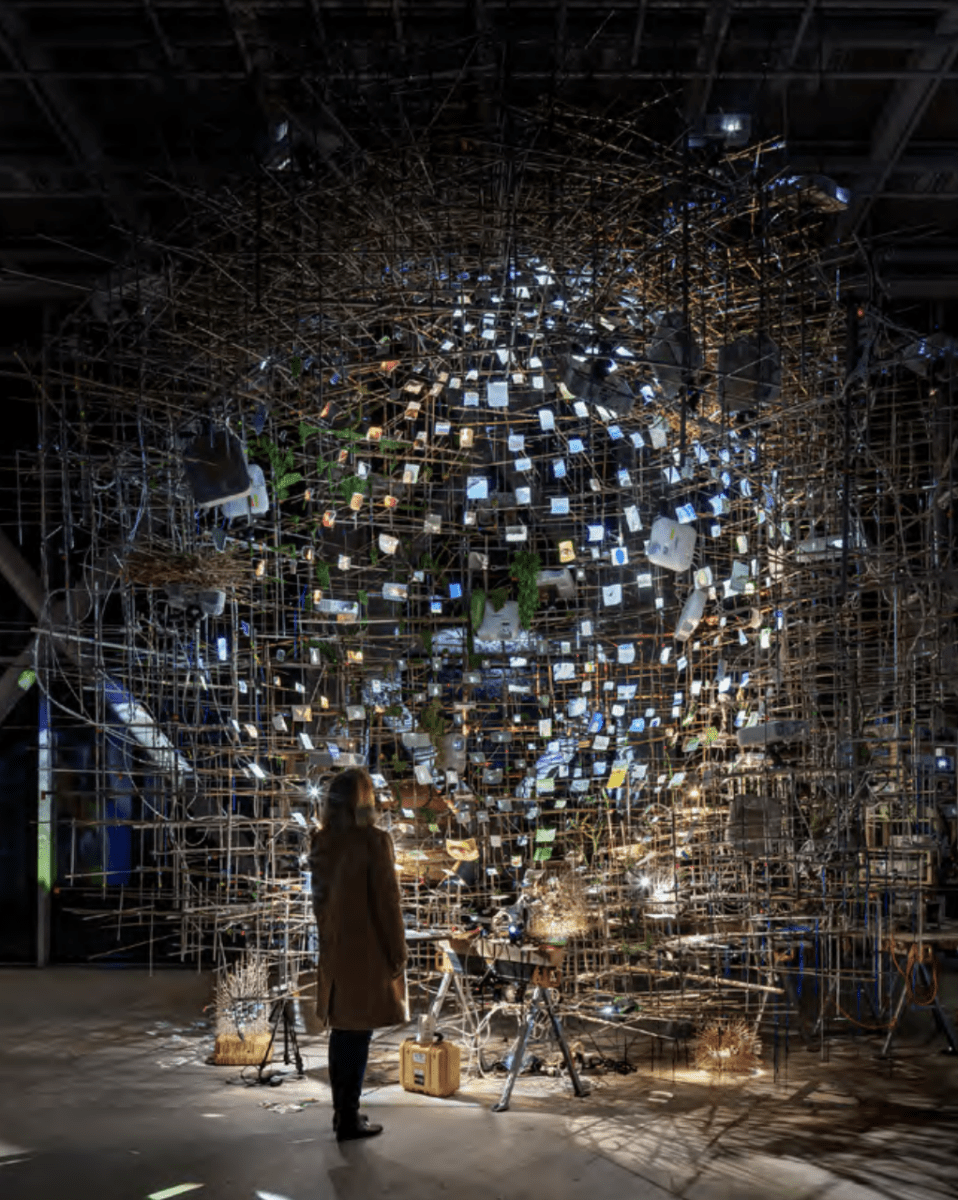

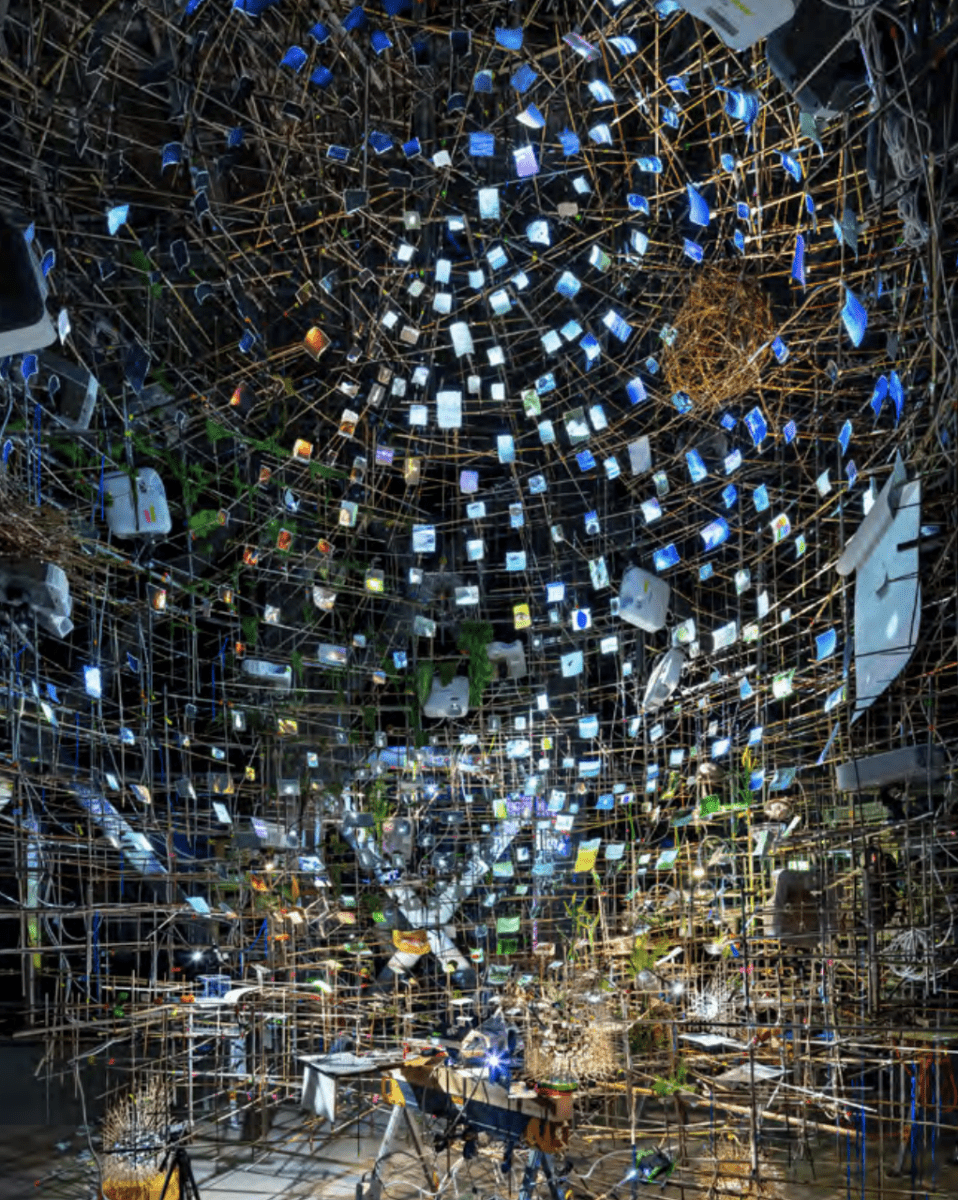

These objects and visuals span from the sublime to the abject, and from the cosmic to the minute. There is a quality of Duchamp-like clutter to many of the items used: household lamps and fans, loudspeakers, ladders, toilet paper, cardboard. But they convey a sense of ineffable grandeur in their meticulous, weblike combinations, particularly when combined with video footage showing natural processes such as the movement of clouds, the flickering of fire, the eruption of geysers or the reflection of light on water.

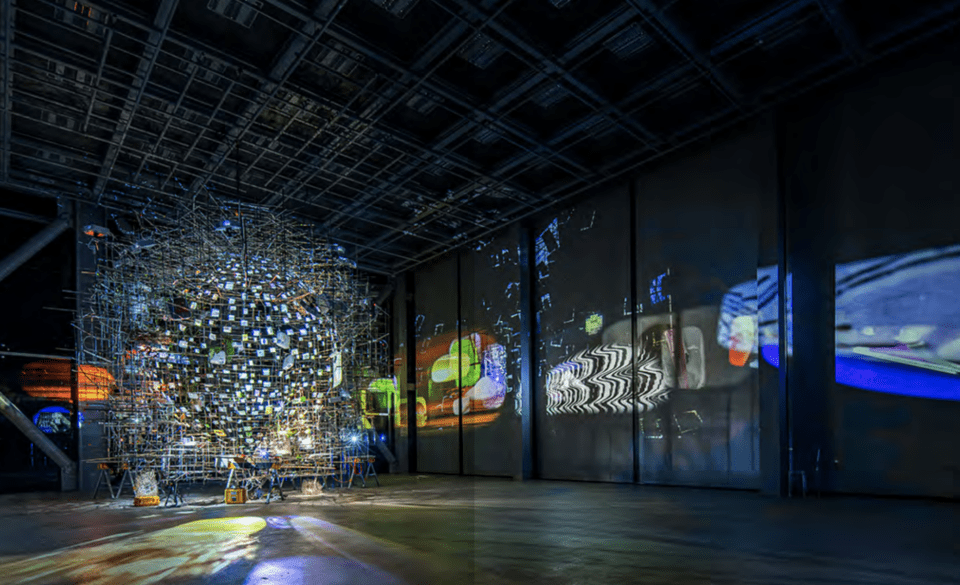

Sze’s sculptures imply different metaphors and relationships depending on the position and context of viewing. Twice Twilight, one of the works included in a recent Fondation Cartier show, seems like a hollow globe or large, Babel-like scaffold glimpsed from afar, but that impression is dispersed up close, when far smaller forms and processes take precedence. But it is not just the density of Sze’s work that explains Latour’s trance-like reaction. It’s also the fact that it never proposes a singular idea or feeling. This quality has been honed by the artist over many years, going back to early works such as Second Means of Egress (1998) and Everything That Rises Must Converge (1999), in which humble domestic objects such as matchsticks and electrical cable take on the dimensions of much larger, architectural or organic entities.

As curator Leanne Sacramone notes elsewhere in the text, Sze’s approach has long been envisaged in combination with elements of film. Sze’s 2000 work Lower Treasury comprised a series of tiny videos of people undertaking different activities, projected onto paper towels, scraps of fabric and pieces of cut glass, shimmering amidst an array of found objects such as sponges, bottle caps and dried flowers. But the practical and financial difficulty of utilising video technology at the turn of the 21st century led the artist towards a more purely object-based bricolage for some years. Throughout this period, however, Sze collected moving images as a “secret” studio practice—many of which were incorporated into later works.

Night into Day represents the re-convergence of film and sculpture in Sze’s practice, responding both to the ease with which video material can now be generated and displayed, and the related fact that digital images and footage have become ubiquitous means of recording the world around us. Sze’s decision to reincorporate film on these grounds gets to the heart of one aspect of what the artist is doing. As Latour notes, Sze’s main subject is the “critical zone,” a tiny layer of the earth’s crust where all sentient life unfolds.

This is a not only a realm of combined natural and artificial phenomena (as reflected in the wide range of things included in Sze’s sculptures), but also one which is perpetually documenting and measuring itself, using scales and systems that are frail, mutable and bound to time and place. In a 1998 interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, Sze’s work was described as offering the opposite: an experience of space with “no beginning and no end, no centre and no edges … that is disorienting, non-hierarchical and sprawling.”

Find out more about Night into Day here.

Words: Greg Thomas

All images from Sarah Sze, Night into Day. Courtesy the artist and Fondation Cartier.