There is an archipelago, made up of over a hundred tidal and barrier islands, midway between South Carolina and Georgia. It is home to the Gullah Geechee, an African American community largely made up of the descendants of former slaves. Daufuskie, one of the region’s major islands, has undergone unprecedented change since the mid-1900s, with ecological disasters, pollution and gentrification all threatening homes and livelihoods. Now, Whitney Museum presents Jeannne Moutoussamy-Ashe and the Last Gullah Island, which is a collection of black-and-white photographs and publications. The exhibition is an archive of collective memory in the face of vast transformation.

There are more than 200,000 Gullah Geechee people living in the costal areas of the Sea Islands. Many of their ancestors acquired land from plantation owners when they fled at the end of the Civil War in 1865. The USA abolished slavery in the same year, which saw discrimination take on a new form. The 1896 “Plessy Case” saw the country’s Supreme Court confirm that it was acceptable to segregate people based on race so long as equivalent facilities were provided. It was known as the “separate but equal” ruling. The decades that followed were marked by the pervasive and brutal influence of the Jim Crow Laws. The statutes, which were effective until 1968, marginalised African Americans by denying them the right to vote, hold jobs, get an education or access many public spaces. The Ku Klux Klan, a white supremacist group, emerged in the same period. In the 1920s, there were 5 million members who instilled terror in Black populations through violence, intimidation and lynchings.

Individuals sought refuge from this onslaught of persecution by establishing their own localities. Scholars such as Everett Fly define “Black Towns” as “settlements founded by formerly enslaved people, usually between the late 19th and early 20th century. The enclaves often had their own churches, schools, stores and economic systems.” These neighbourhoods were found across the USA, including Shankleville, Texas and Langston City, Oklahoma. Residents maintained a shared culture through food, knowledge, language and music. However, as the 20th century dawned, relentless modernisation, racial attacks and industrialisation threatened these long-held traditions and customs. There were more than 1,200 “Black Towns” flourished across the USA between the 1880s and 1915, but today as few as 30 still exist. Violent outbursts were often targeted at these areas, threatened by their success. One such example is the Tulsa Race Massacre. In 1921, white mobs attacked residents and destroyed homes and businesses in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma, which was a thriving African American region known as the “Black Wall Street.”

The same problems were true for the inhabitants of Daufuskie Island, a Black Town more than 1,000 miles away. There was an infestation of cotton cropa by insects in the early 1900s, which had a long-lasting impact on the economy and infrastructure. Jobs disappeared as pollution from the Savannah River contaminated its once-thriving oyster beds. Real estate developers began circling in the 1970s, emboldened by nearby Hilton Head Island’s burgeoning reputation as a profitable tourist destination. The population of Daufuskie dropped to around 80 residents in the 1980s, their whole way of life on the cusp of vanishing.

Whitney’s exhibition centres Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe’s desire to document this rapidly shifting culture. The activist and scholar is known for photographs that testify to the beauty and complexity of Black life in America. In 1977, she began making work among the Gullah Geechee after returning from a six-month period in West Africa. Moutoussamy-Ashe saw these two locations at intertwined, each part of a wider narrative about the Black diaspora. Kelly Long, Senior Curatorial Assistant at the Museum said: “Jeanne’s photography is part of a larger practice rooted in a serious sense of responsibility to other people – to the affirmation of lives and legacies that might otherwise exist only in memory. Nowhere is this more poignantly or poetically expressed than in her pictures of Daufuskie Island and in her connections to its people, which she nurtures to this day.”

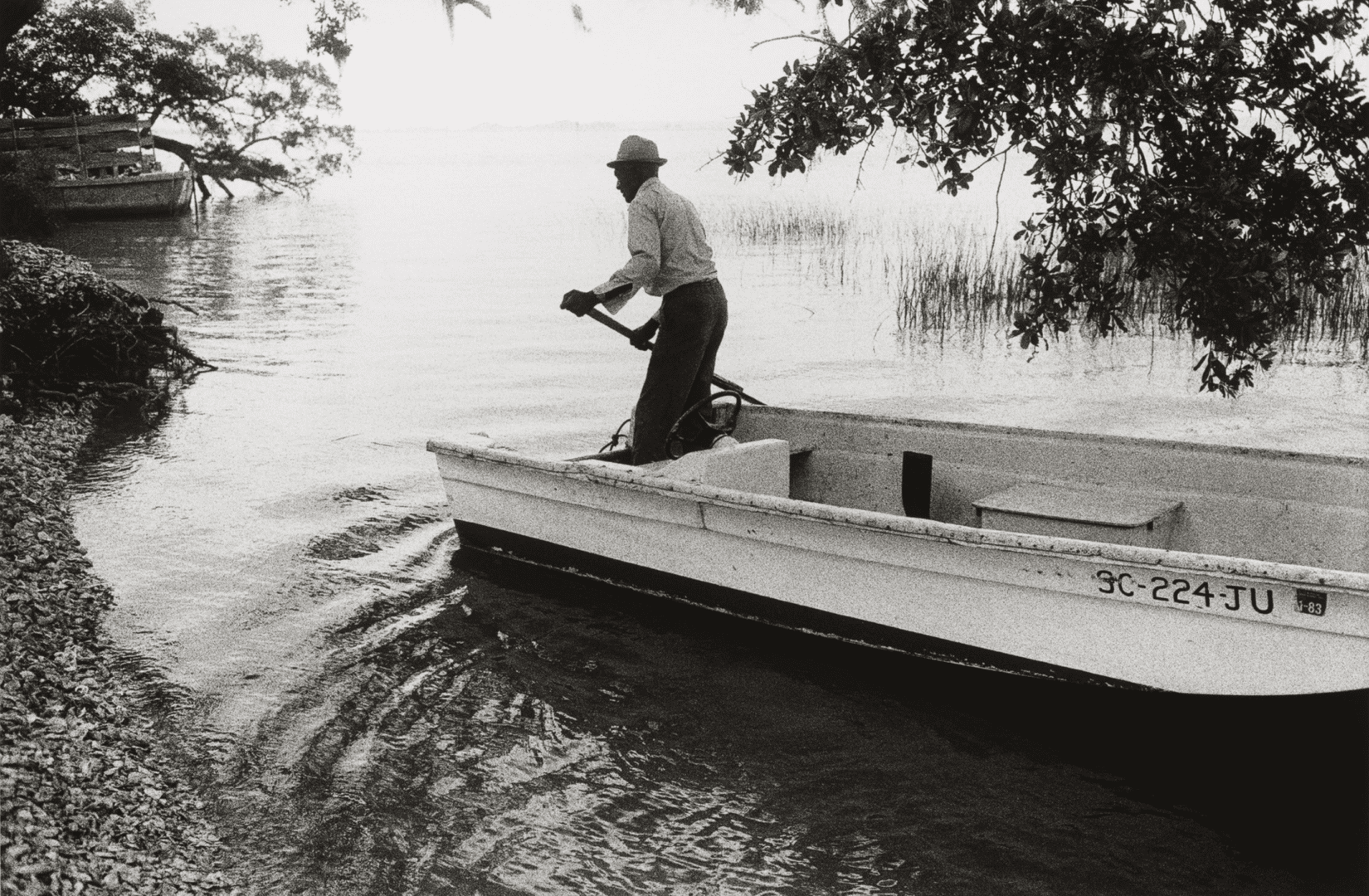

The show includes portraits of children, people at work and rest and community elders, images of homes and the shoreline, people in employment and at rest and church services. Together, they form an impression of a place caught between former habits and a new reality. A particularly poignant shot is of a wedding party, gathered together outside of the Union Baptist Church. Their numbers, only around 40 guests, represent half of the permanent residents left on the Daufuskie Island at the time. Yet, the photos are not somber in their acknowledgement of a shrinking community. There is joy to be found in the ceremonies, celebrations and daily life, which is an idea central to the artist’s vision. The pictures, taken between the 1970s and 1980s, saw Moutoussamy-Ashe go from an outsider to a trusted figure. The result is not only an important record of Gullah Geechee life, but of a key part of American history.

Jeannne Moutoussamy-Ashe and the Last Gullah Island is a testament to the power of art to preserve shared experiences. The show puts the Gullah Geechee people at the heart of conversations about Black identity, representation and cultural legacy. Today, the people of Daufuskie still struggle against time, development and environmental upheaval to sustain their unique customs and traditions. Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe’s images continues to strike a chord and provides a vital archive of a society on the brink of irreversible change.

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe and the Last Gullah Islands is at Whitney Museum of American Art until May 2025: whitney.org

Words: Emma Jacob

Image Credits:

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, Jake and his Boat Arriving on Daufuskie’s Shore, Daufuskie Island, SC, 1981, printed 2022. Gelatin silver print, 15 × 22 1/2in. (38.1 × 57.2 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, NewYork; purchase with funds from Donna Perret Rosen and Benjamin M. Rosen 2023.114.6. © Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe.

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, A Man Standing in Front of Union Baptist Church, Daufuskie Island, SC, 1979, printed 2022. Gelatin silver print, 16 1/4 × 22 3/8in. (41.3 × 56.8 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from Donna Perret Rosen and Benjamin M. Rosen 2023.114.4. © Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe.

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, House with Clothesline, Daufuskie Island, SC,1979, printed 2022. Gelatin silver print, 1415/16×221/2in. (37.9×57.2cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Director’s Discretionary Fund 2023.114.7.© Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe.

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, Miss Bertha, South Carolina, 1977, printed 1997. Gelatin silver print, 8 3/4 × 13 1/4in. (22.2 × 33.7 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Michael I. Jacobs in honor of Sylvia Wolf 2001.188. © Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe.

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, The Bride, the Groom, and their Guests, Daufuskie Island, SC, 1980, printed 2022. Gelatin silver print, 14 15/16 × 22 1/2in. (37.9 × 57.2 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from Donna Perret Rosen and Benjamin M. Rosen 2023.114.8. © Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe.