This year is monumental for Liverpool. In May, it hosted Eurovision on behalf of Ukraine and this month, the city’s Biennial returns. uMoya: The Sacred Return of Lost Things considers the past, present and future of society, marking the event’s 25 year anniversary with an atmosphere of reflection. Galleries, historic spaces and hidden gems play host to an array of free events, exhibitions and new commissions that trace ancestral and indigenous knowledge. Cape Town-based independent curator Khanyisile Mbongwa brings more than 30 international artists together with local residents in the search for “a return to self that aligns the celestial and ancestral, where one is not denied access to themselves.” A collaborative sprit is threaded throughout the programme, identifying and reclaiming “all that is lost or stolen” through 14 weeks of creative expression, celebration and repair. Here, we highlight 5 artists from the programme who enliven the city with new perspectives on identity, community and territory.

Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński | FACT

Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński (b. 1980) partners with sound-artist Bassano Bonelli Bassano (b. 1983) and Black residents from the local area for a new installation. Video and sound collide in Respire (Liverpool) (2019), providing a space for expression, healing and learning. Waves of sound move between the individual and collective in this dynamic audio conversation, imagining a reality where performers create, share and transform spaces for breathing. Red balloons slowly inflate, obscuring participants’ faces.

Nicholas Galanin | Bluecoat

What methods can we use to seek joy amidst catastrophe? Nicholas Galanin (b. 1979) responds to this question in k’idéin yéi jeené (‘you’re doing such a good job’) (2021). Sampled words of admiration, love and hope for the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America are expressed in their native tongue: Lingít. The intimate track addresses false historical narratives and prejudice, bringing individuals from these communities together to share their ceremonies, cultures and knowledge.

Edgar Calel | Tate Liverpool

The first examples of ancestor worship can be traced back to the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE), when dedicated templates were built for rulers’ predecessors. Edgar Calel’s (b. 1987) Ru k’ox k’ob’el jun ojer etemab’el (The Echo of an Ancient Form of Knowledge) draws on his Mayan Kaqchikel heritage, sharing traditions of ritual and offerings in a multi-layered sculptural installation. Ripe bananas, grapes, leeks and pineapples balance on jagged stones, placed during a private ceremony prior to the exhibition opening.

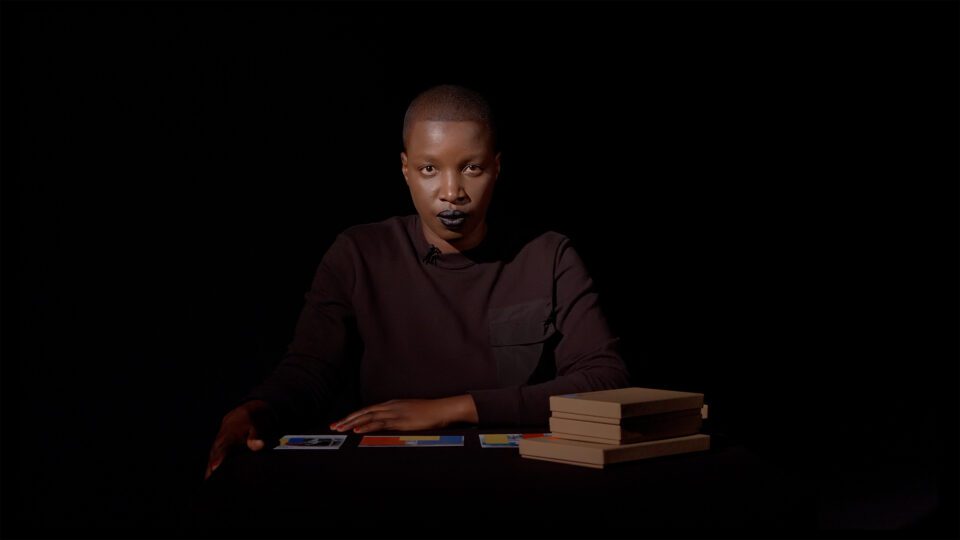

David Aguacheiro | Open Eye Gallery

Mozambique is home to some of the world’s largest untapped coal deposits. It is also set to become the largest exporter of liquefied natural gas, as overseen by BP. Mozambican artist David Aguacheiro (b. 1984) navigates the longterm impacts of extractivism. Poignant portraits are complex and layered, drawing connections between the loss of essential resources and people’s clothes, identity and traditions. The artist’s home country changes irrevocably as natural resources are lifted from the ground.

Lorin Sookool | St Luke’s Bombed Out Church

Woza Wenties! (2023) responds directly to Liverpool Biennial’s title by combining fluid movements to position the body as a site for change. For the new commission, which will be performed at the event’s opening weekend, Lorin Sookool (b. 1991) responds to the violet erasure of Blackness during her youth. Modernist systems of dance and improvisation transform the body in an act of decolonisation, responding directly to the artist’s personal experiences of attending school in South Africa.

Liverpool Biennial | 10 June – 17 September

Words: Saffron Ward

Image Credits:

1. Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński, Respire, (2019). Courtesy of the artist. ©Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński

2. Belinda Kazeem – Kamiński, Unearthing. In Conversation, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien. © Belinda Kazeem – Kamiński

3. Nicholas Galanin, Never Forget, (2021). Courtesy the artist. Photograph by Lance Gerber

4. Edgar Calel, Ru k’ ox k’ob’el jun ojer etemab’el (The Echo of an Acient Form of Knowledge), (2021). Courtesy of the artist and Proyectos. Ultravioleta. Photo by James Retief

5. David Aguacheiro, Plastic Life, (2020). Courtesy of the artist. Photograph by Tina Krüger

6. Lorin Sookool, Project ongoing, (2022). Photography by Tanja Hall