When we hear the term ‘climate crisis’, our minds will often jump to images of icebergs melting, severe weather events or the destruction of natural environments. Of course, all of these are accurate realities of what climate changes does to our planet, but there are many human-caused changes that are often overlooked. In fact, it affects almost every facet of our existence. A 2024 study revealed that the climate crisis is making our days longer, and it is predicted that it will cause the average world income to diminish by nearly a fifth by 2050. Now, LOOK Photo Biennial 2024: Beyond Sight is at Open Eye Gallery, exploring the complex and often forgotten human relationships with nature. The exhibition builds on the LOOK Climate Lab, which invited researchers, artists, academics and visionaries to take over the gallery to showcase how photography and visual art can communicate the climate emergency in accessible ways, transcending languages, borders and cultures. Split into three projects, focusing on the light pollution, the disposal of materials after conflict and the environmental impact of silver usage respectively, the show brings to light the delicate and complex relationship between humans and the natural world – and reminds the viewer that we all have a part to play in preserving our home.

Created by artist Mattia Balsamini, Protégé Noctem is a visual research project dedicated to the disappearance of the night. International attention was drawn to this topic when the World Atlas of Night Sky Brightness was published in 2016. The computer-generated map, based on thousands of satellite images, allowed anyone to view how and where the globe is lit up at night. It revealed that only the most remote areas of the planet – Siberia, the Sahara, the Amazon – are in total darkness. More than 80% of the world’s population, and 99% of Americans and Europeans, live under ‘sky glow’. This brightening of the nighttime hours, due to cars, streetlights, offices, factories, outdoor advertising, and buildings, can be detrimental to both human health and animals. The reduction of natural nighttime confuses the circadian rhythm and reduces the amount of melanin produced in the body, which can result in sleep deprivation, fatigue, headaches, stress, anxiety and potentially more serious health conditions like cancer. For animals such as sea turtles and migratory birds who are guided by moonlight, artificial light becomes confusing, causing them to lose their way. Balsamini explains why light pollution is a significant issue, and his images of the night sky remind us of the unique and rare beauty of a clear view of the stars. Meanwhile, his images of landscapes backlit by an urban luminosity make sky glow starkly evident. He makes a strident defense of darkness as crucial to health, scientific research and protecting wildlife.

In Stephanie Wynne’s exhibition, the focus is on how in the years following WWII, the structural waste and war was disposed of or reused. The ideas explored reverberate with current conflicts around the world and asks vital questions that are as relevant today as they have ever been – when a conflict is over, how does the structure of a city or landscape recover? Liverpool and the surrounding areas, in particular Bootle and Birkenhead, were subjected to heavy bombing during the May Blitz of 1941. Over the course of the war, 4,000 people were killed, 10,000 homes destroyed and 70,000 citizens were made homeless. This devastation produced tonnes of rubble and the cleaning of bombsites saw this collected and deposited on a mile-long stretch of the coast at Crosby Beach. For many years, vegetation grew and covered most of it, but due to costal erosion the tide is now uncovering remnants of those lives and homes. Wynne, was born and raised in Merseyside, said: “this mosaic of bricks, masonry, tiles, concrete, marble, reinforcing steel and glass is the archaeology of a lost city that is steadily being revealed.” The work on display is born out of a desire to record this unconventional beauty and create a link with her own family history. Her images give the viewer a glimpse of past lives, encouraging us to consider the lives that were made within those bricks. Some images were taken at night and lit by torchlight, to reflect the hours of darkness when people sheltered from bombing raids. They are a reminder of the generations that came before, and of the fact that the materials we use to build our lives exist beyond us.

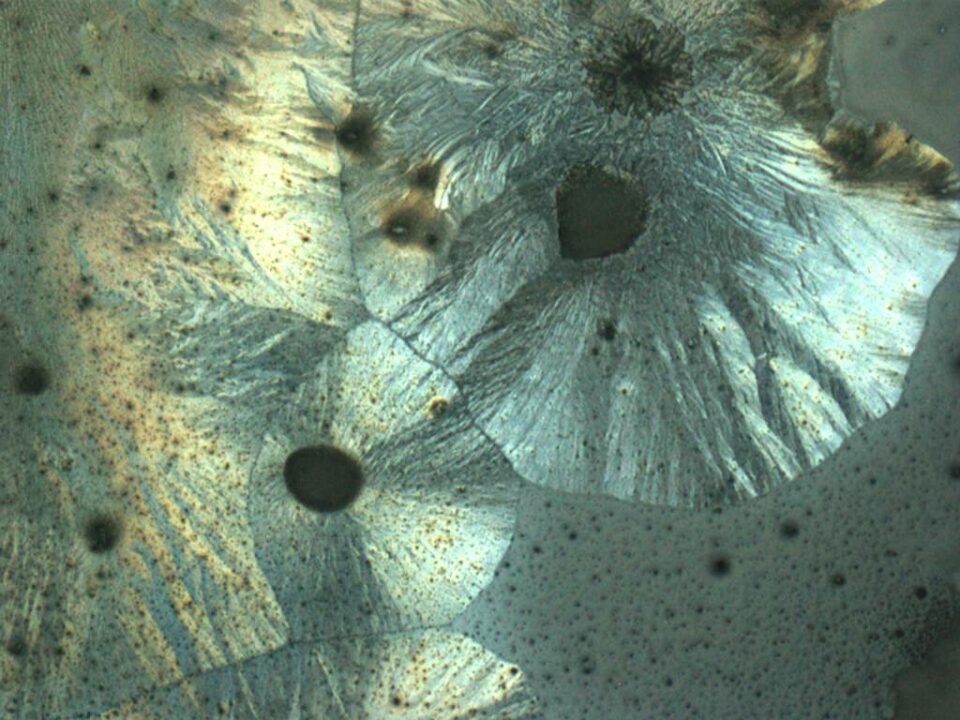

The final project in the Biennial is Melanie King’s consideration of the lifecycle of silver and pallidum, from their production within the cosmos and extraction from the Earth to their use in photography. The thing that makes Dr King’s exhibition so unique is her commitment to demonstrating methods and materials that are less harmful to the environment. Not content with simply suggesting new ideas, the artist implements them into her practice to showcase how these methods can be practically applied. She produced silver gelatin photographic prints of the night sky using a developer made from coffee. The images release silver into the photographic fixative when developed, so King used electrolysis to safety reclaim the silver from the fixer. This was then used to plate copper jewellery, meaning the metal is prevented from entering the water system and negatively affecting the environment. To do this, the artist acquired silversmithing skills to ensure she could turn the recycled silver into beautiful pieces and to better understand the material on a microscopic level. The majority of silver recycled each year, approximately 5000 tonnes, comes from electronics and photographic film. King’s work is a reminder that the photography and the natural world are not so far removed, and it is essential that image-makers continue to create their art in a way that leaves as little a trace on the environment as possible.

LOOK Photo Biennial 2024: Beyond Sight will run until 1 September: openeye.org.uk

Words: Emma Jacob

Image Credits:

1. Stephanie Wynne, The Erosion.

2. Elephant Trunk Nebula, Platinum-Palladium Print, 2021. Image originating from NASA, printed by Melanie King.

3. Mattia Balsamini, Protege Noctem.