Herd immunity. Minimise the spread. Stockpile. Staycation. Quarantine. The language of the Covid-19 pandemic has been seared into the collective consciousness, with Google reporting “When will lockdown end?” and “When will I get the vaccine?” amongst 2021’s most-searched queries. Bindi Vora (b. 1991) is an artist and curator interested in this rhetoric. “I felt quite overwhelmed by the information being thrown at us – what to do and how to behave,” Vora recalls. “With life as we knew it in flux, I felt compelled to make something as a response and an outlet.” The result was Mountain of Salt, a series of 370 photomontages bringing together found images, appropriated text and digital shapes. Vora explores the dynamics of liberty and power, visualising how various global events played out from 2020-2021. Mountain of Salt was first shared on Instagram and has since been shown globally at Singapore International Photography Festival.

A: You began Mountain of Salt in March 2020, at the height of the pandemic. Can you expand on the circumstances surrounding the work’s origin?

BV: Just before the first lockdown was announced in 2020, my partner and I were on holiday in the Atlas Mountains – we decided to take the risk at the time as the cases were less than ten in Marrakech, and we thought we would be safe. We found out the border in Morocco was imminently closing and it could be months before it reopened. Even as we sat on one of the last flights out – people coughing, getting agitated, racial slurs being thrown around – there was a chance we could still find ourselves stranded. This really was the genesis for the work, and I began by collecting language – from politicians, journalists and individuals who were sharing their commentary, thoughts and directives. This material was collated through a multitude of platforms: daily briefings, Twitter commentary, news articles and slogans on placards from the Black Lives Matter protests, such as “Statues Are Not Neutral.” I was so drawn to the energy of language at this time – this invisible weight it placed upon me. The language was incredibly triggering and kept bringing me back to the starting point of how I felt at the beginning of the pandemic. Reflecting on where we are over two years on, I still don’t feel like I’ve digested this experience.

A: Why did you decide to combine text and images in the way you did?

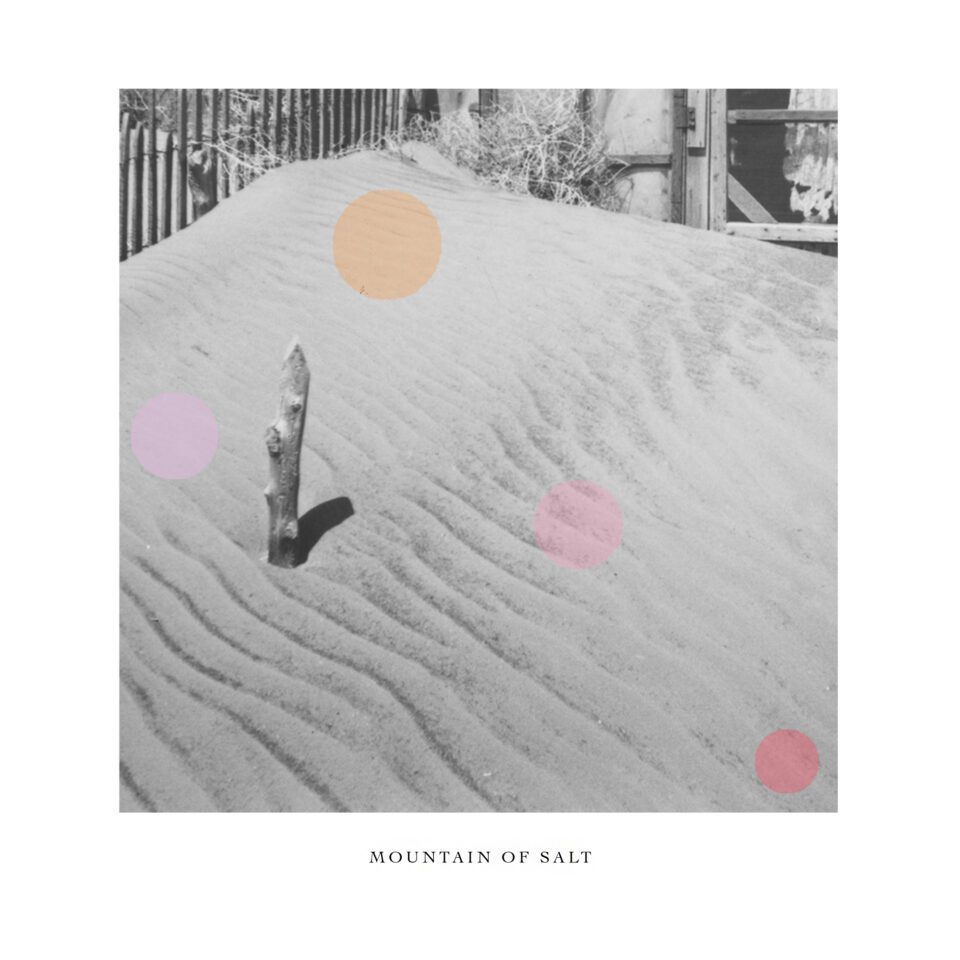

BV: The collages developed organically; the process would always begin with language. From there, I’d literally spend hours sifting through the archive of photographs I’ve been acquiring for over a decade – from eBay, New York Public Library digital collections and other sources – to find the right image. The digital shapes you see layered on the surface are placed strategically, not only to direct the gaze to various intricacies within the composition or to ask you to pause in the small space, but also as a way of speaking to the semantics of what the shapes represent: balance, community, totality, union.

A: Collage is a technique you’ve used elsewhere. What does it allow you to do?

BV: Collaging for me has always been a way of juxtaposing myriad trajectories into one visual plane. In 2011, I made a small artist book titled Journeying a Non-Place, a topographical visual map made of photographs of Paris streets. I was walking them for the first time as an adult – navigating my way through the city. Ultimately, this format became an exercise in locating and dislocating. For Mountain of Salt, this medium felt familiar; the pieces are small – each approximately 20 x 20 cm. It was about conceptualising colossal moments into something you could grasp in your hands.

A: When working with found images, how do you relate to them and their histories? Are they a kind of visual source material or do they bring their own contexts with them?

BV: Working with collections of images is fascinating – I feel like our relationship to these objects changes as the world around us changes. It’s an organic repository that continues to provide rich connections, questions and multiple lines of enquiry. Mountain of Salt was really about highlighting the sentiment that moments, ideas and visuals are recurring. The found photographs vary in terms of their age, finish and type – from early stereoscopes to Polaroids, medium format prints and press photographs – but all are markers of time. Applying the same treatment and cropping them to the same size created a sense of uniformity, where language and image sit in tandem. It was a way of re-archiving and reprocessing the material. The series expanded beyond the pandemic and is punctuated by issues of global, urgent concern that have created waves: equality, hyper-vigilance, Brexit, pledges of reform, political buffoonery.

A: Your work is grounded in the tactile, using objects such as paper or analogue film formats, whilst being very much concerned with ideas. What motivates you as an artist?

BV: My practice shifted 10 or so years ago as I became interested in the physical object – the textures, the possibilities and the details that people would usually overlook. How much can a surface be pushed before it is changed? I worked in a lab during school and through college, where we would process rolls and rolls of 35mm film. We chopped off and discarded the ends so they fit six-to-a-strip in plastic holders. As I looked at my own negatives, I found such beauty in these markings; they located a place without showing it. This resulted in the Film Ends (2012 – ) series. My ideas come in various ways – sometimes through reading, sometimes through an experience. I am inspired by artists Lorna Simpson, Hannah Höch and Njideka Akunyili Crosby, as well as writers Rebecca Solnit and Donna Harraway. They provide an alternative way of seeing and understanding the world, and how our histories shape us.

Interview by Rachel Segal Hamilton.

Image Credits: Bindi Vora, Mountain of Salt (2020 – 21). A series of 367 works. Found photograph, appropriated text and digital shape collages on Hahnemühle fine art pearl paper; 20.32 x 20.32 cm All works © / Courtesy Bindi Vora