Muholi is a visual activist whose images reclaim the lens, offering a vital platform for black lesbian, gay, transgender and intersex individuals.

Zanele Muholi’s (b. 1972) images have captivated the world. Creating direct, powerful portraits, the South African artist and visual activist works across photography, video and installation, focusing on race, gender and sexuality. Muholi uses the lens as a space for reclamation – of both gaze and representation. The artist has won a number of prestigious prizes, accolades and honours, including an Infinity Award from the International Center of Photography in 2016, a Chevalier de Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 2016 and an Honorary Fellowship of the Royal Photographic Society in 2018. This autumn, Tate Modern, London, presents the artist’s first major UK survey. Sarah Allen, co-curator of Zanele Muholi 2020, expands on the themes in the show as part of Tate’s wider programming, as well as the impact of this groundbreaking work over the last few decades.

A: How did Zanele Muholi’s artistic career begin?

SA: Muholi’s entrance to the art world was through activism. Amongst early activist work they wrote for the queer blog Behind the Mask, and in 2002 they co-founded Forum for the Empowerment of Women (FEW) in Gauteng – a non-profit organisation that promotes and protects the rights of lesbian, bisexual and transsexual women and provides a safe space for these people to meet and organise. In 2003, they graduated from Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg. Shortly after in 2004, Muholi’s first solo exhibition – Visual Sexuality: Only Half the Picture – was presented at the Johannesburg Art Gallery. This, along with their inclusion in the group show Is Everybody Comfortable? at Museum Africa, Johannesburg, and as part of a conference at the University of Western Cape entitled Gender & Visuality, garnered national media attention. It was very clear that Muholi had an unflinching and unique approach to an important subject matter and their career progressed quite quickly from then.

A: Muholi devoted years to the Faces and Phases series (started in 2006), which directed the camera at members of the black lesbian and trans community in South Africa. Can you discuss how this series began, and how it developed over the years that followed?

SA: The first image that Muholi shot for Faces and Phases was of Busi Sigasa – a talented activist and poet who has written a beautiful poem called Remember Me When I’m Gone, which will feature in the Tate show this autumn. The importance of creating an archive to commemorate and celebrate the lives of black queer individuals in South Africa really built from that first portrait. The series now includes several hundred portraits of lesbian, trans men and gender non-conforming individuals. This is an ongoing project for Muholi, who returns to re-photograph participants again over time. It is a lifelong series and a living archive. I find that level of artistic dedication incredibly moving. A really critical element of the project is giving voice to the individuals so that they can speak for themselves rather than be spoken for. The publication Faces and Phases includes many testimonies from the participants which reveal the diversity of the black queer community. Currently, I am reviewing video testimonies that will feature in the exhibition. Within these works, the participants tell their side of the story, sharing their experiences and powerful testimonies of navigating gender, sexuality and race in South Africa today.

A: Muholi started the series in the same year that South Africa – the only country on the continent – legalised same-sex marriage. Of course, discrimination and violence are still rife in South Africa, and across the entire world, in spite of this legislation. How do these images remedy a history of black queer invisibility?

SA: It is without doubt that black queer individuals in South Africa suffer from under-representation and a certain level invisibility. But equally, writer Pumla Dineo Gqola makes the important point that they also suffer from a state of “hyper- visibility” – one which can make them the target of homo- phobic hate-crime. The overwhelming narrative of black lesbians in the media in South Africa then becomes one of victimhood. This dichotomy between visibility and invisibility is at the core of Muholi’s work. They document survivors of hate-crimes but also try to create a form of counter-representation against the predominant narrative by creating a positive visual document that will live on beyond them.

A: Why did Muholi move onto self-portraiture? What new creative and professional avenues did this genre lend? SA: Although many people know Muholi’s work from the powerful Somnyama Ngonayama series, Muholi actually took self-portraits from a very early point in their career – and we will show many of these important works at Tate. One of the reasons they made a more decisive turn towards this medium is the need for self-healing. Muholi spent many years documenting the hardships of their community in South Africa – which have included many deaths, murders and corrective rapes. Somnyama Ngonyama offered an opportunity to heal some of these personal wounds whilst also addressing broader issues related to race and representation.

A: The Somnyama Ngonyama (Hail the Dark Lioness) series includes self-portraits, presenting alter egos that boldly hold the viewer’s gaze. How does this body of work, and the Brave Beauties series come together to challenge Eurocentric definitions of beauty?

SA: Beauty is a powerful word to describe Muholi’s body of work. But it isn’t a beauty born by artificial means – in Muholi’s portraits of others they don’t employ elaborate lighting, makeup or staging techniques. Rather, each participant projects their own beauty on their own terms. In relation to challenging Eurocentric definitions of beauty I think one could read the darkening of skin tone in Somnyama Ngonyama as an act of reclaiming blackness – of challenging a dominant conception of lighter skin as a canon of beauty.

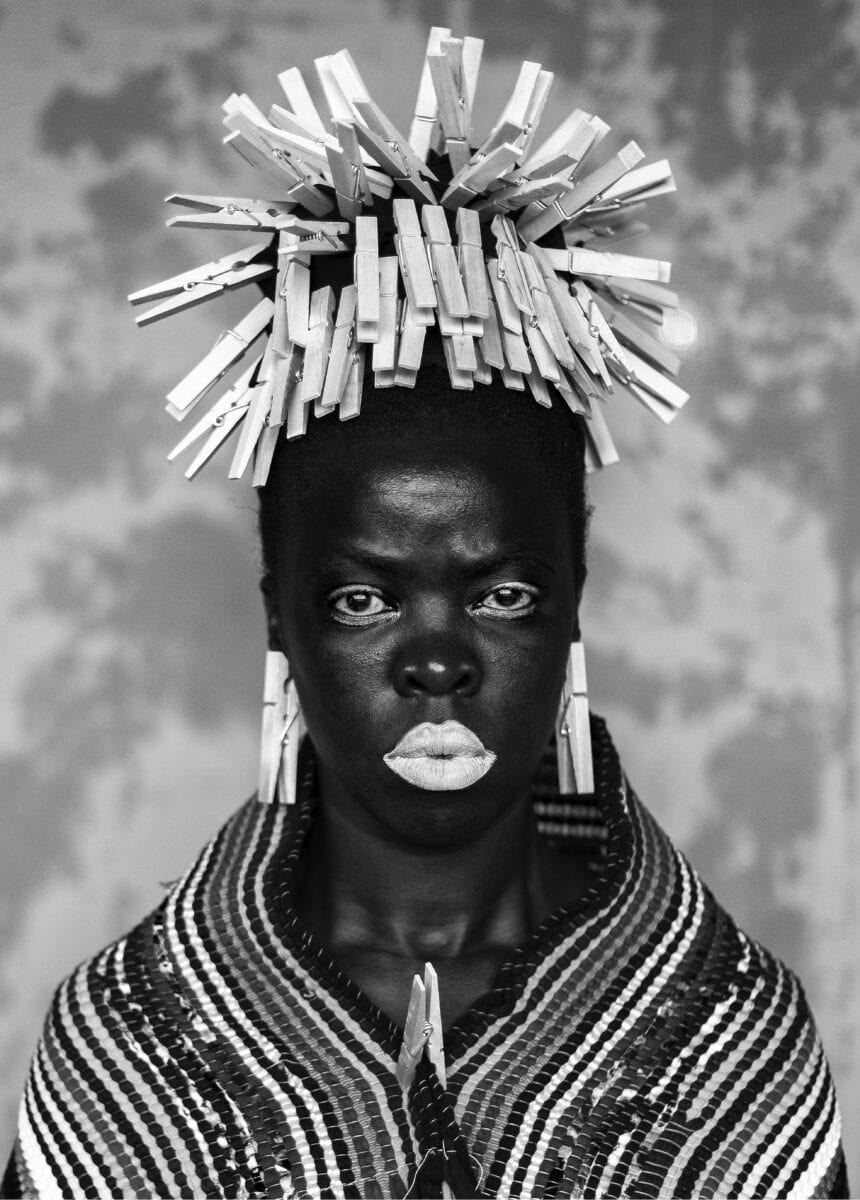

A: The artist’s head is often crowned with everyday objects, such as pegs, sponges and hair picks. What do these objects signify? How do they operate, both thematically and structurally in each piece?

SA: Muholi uses material often sourced from their immediate environment. The various materials speak to particular issues or histories. For example, in Nolwazi II, Nuoro, Italy, 2015, they are crowned in felt-tip pens. This references the “pencil test” devised to assist authorities in racial classification under apartheid. When authorities were unsure how a person should be classified, a pencil would be pushed into their hair. If the pencil fell out, signalling that their hair was straight (white) rather than curly (black), the person “passed” and was “classified” as white. However, there are other por- traits which are much more pared back and don’t feature objects or additional material. I find these images the most haunting. One of my favourite Somnyama images is called Mfana, London 2014. It’s a tightly cropped portrait of Muholi staring at the camera straight on. For me personally, it is so raw and honest, as if they have broken through all the white noise of other people’s representation and projections.

A: Muholi has noted that their self-portraits pay tribute to family members, LGBTQIA+ communities and many more. To what extent do the images act as “dedications”? SA: The images you refer to, in which Muholi uses pegs and sponges, are dedicated to their mother Bester Muholi, who was a domestic worker for the same middle-class white family for over 40 years. Another image, which is a dedication of sorts, was made in memory of the South African activist Fezekile Ntsukela Kuzwayo. Jacob Zumba was charged with the rape of Kuzwayo in 2005, but was acquitted in 2006. Zumba went on to become president of South Africa in 2009 until his resignation in 2018. Kuzwayo died in 2016 and Muholi made a self-portrait soon after to mark her passing. Though some images act as dedications, Muholi has spoken about how the series can be understood as an attempt to use the body as a canvas to “bring forth political statements.”

A: Exhibitions like this have never been more important, dedicating major public institutions to the display and celebration of black bodies. How does this exhibition sit within Tate’s response to Black Lives Matter and to diverse cultural programming for the future?

SA: Whilst this show has been many years in the planning, it of course holds an even greater resonance in this current moment. I hope it will be a catalyst for more conversations about important issues – not only about race but the LGBTQIA+ community. We’re hugely committed to not only continuing to broaden representation in our programme and collection but also our workforce. Over this year, we’ve held Steve McQueen’s Year 3 series at Tate Britain and solo exhibition at Tate Modern, as well as Kara Walker’s Fons Americanus in the Turbine Hall. We’re also looking forward to Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s exhibition at Tate Britain this autumn. This is just a snapshot of some of the work we’re doing. Tate has an influential platform and it’s important we use it to speak out about racial inequality. Our wider aim is to become truly inclusive with a workforce and audience as diverse as the communities we serve. Muholi has often spoken about how they would like to “turn museums into spaces where we can carve out a new dialogue that favours us.” We are working hard to make sure this show achieves that goal.

A: What kind of resources are Tate looking into for educating staff and attendees about the exhibition?

SA: We want our staff and visitors to have the tools they need to explore the exhibition and its themes. We are look- ing at doing this in a number of different ways – including commissioning a glossary that deals with terms that are pertinent to Muholi’s practice – and we plan to make contact details for key organisations available in the gallery.

Words

Kate Simpson

Zanele Muholi ‘s new exhibition dates run 5 November – March 2021, Tate Modern, London

Image Credits

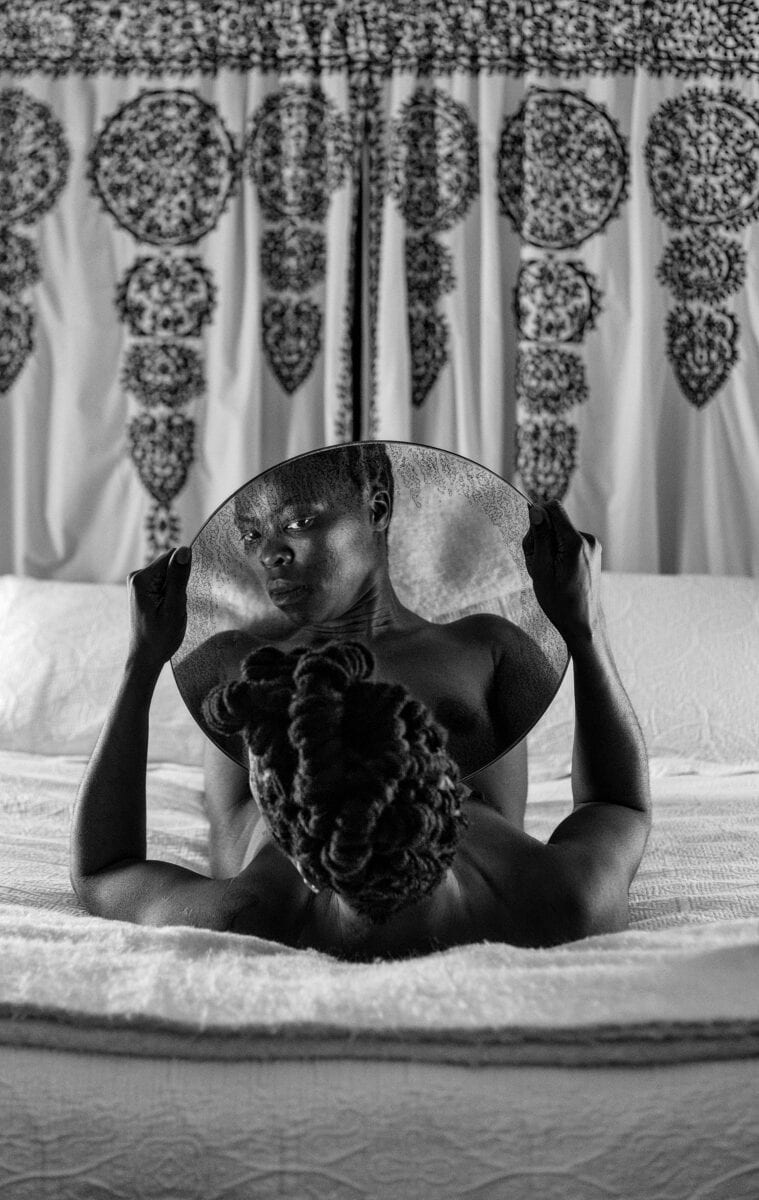

Lead image: Qiniso, The Sailes, Durban 2019. Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York. ©Zanele Muholi.

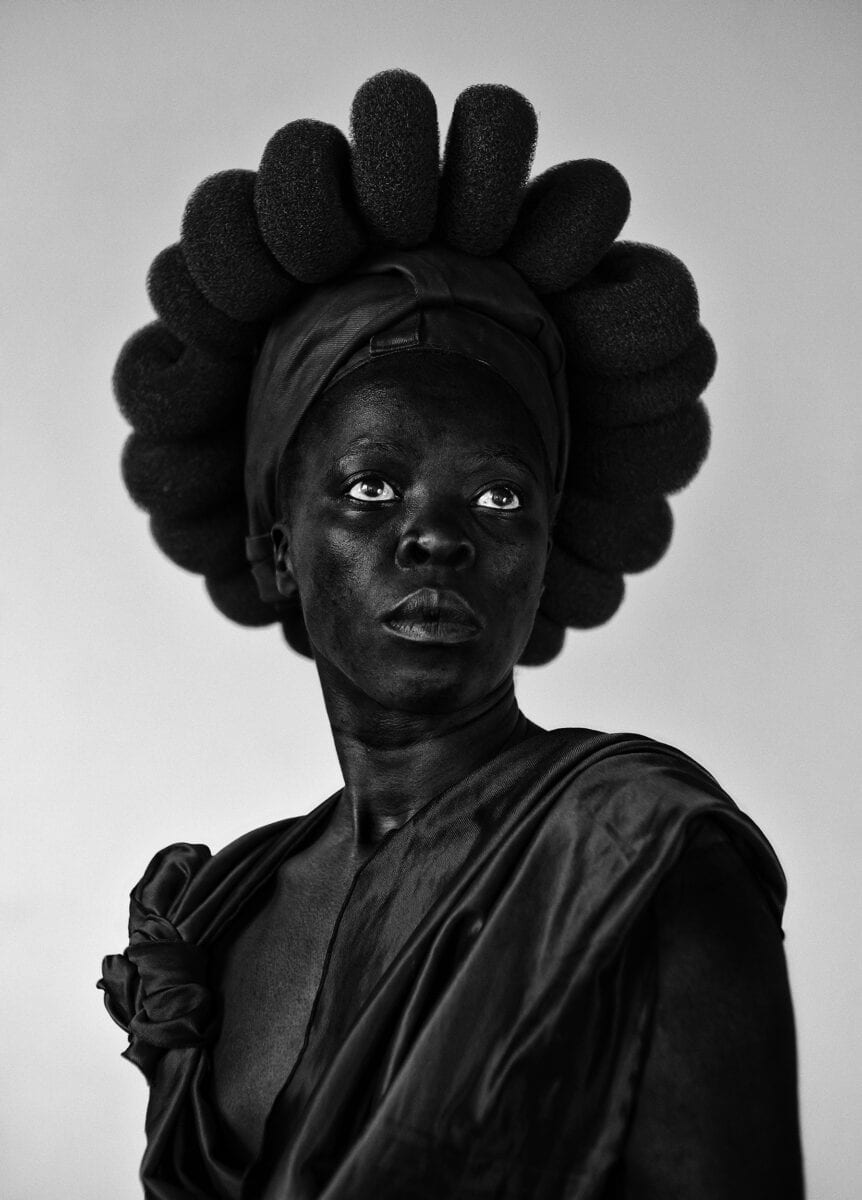

1: Zanele Muholi (b.1972), Bester I, Mayotte 2015. Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper. 700 x 505 mm. Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/ Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York. © Zanele Muholi.

2: Zanele Muholi (b.1972), Ntozakhe II, Parktown 2016. Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper. 1000 x 720 mm Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York. © Zanele Muholi.

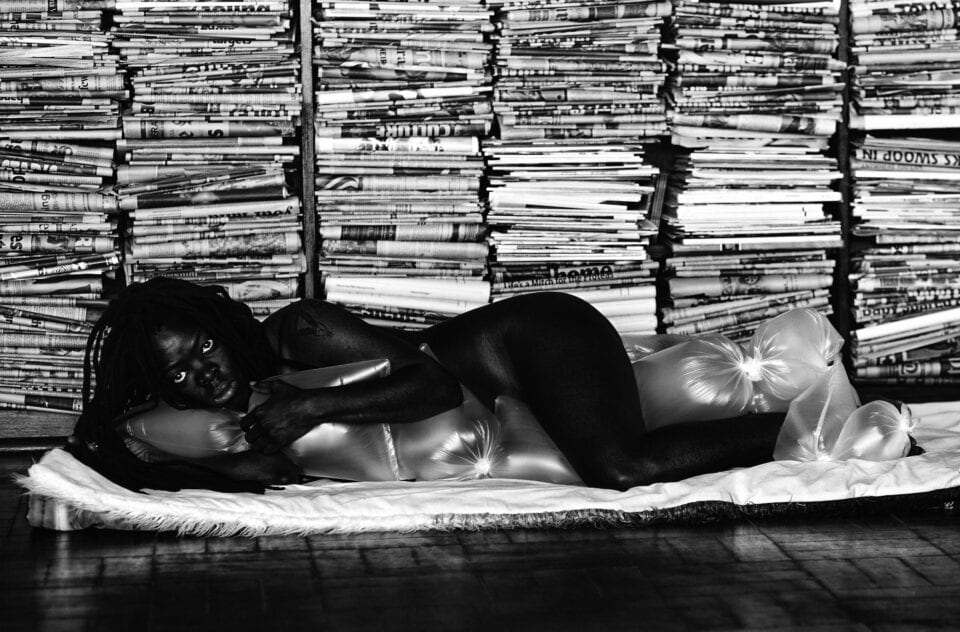

3: Zanele Muholi (b.1972), Julie I, Parktown, Johannesburg 2016. Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper. 660 x 1000 mm. Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York.© Zanele Muho

4: Qiniso, The Sailes, Durban 2019. Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York. ©Zanele Muholi.