Viewing through a different lens: representations of pop, advertising, psychology and autobiography through the eyes of experimental photographer Anne Collier.

In American photographer Anne Collier’s image, Cut (Color) (2009), we are presented with the close-up photograph of an eye being spliced through the centre. The comparison between this, and the infamous eyeball-slicing scene from the 1929 surrealist film Un Chien Andalou is indisputable. However, where filmmaker Luis Buñuel and artist Salvador Dalí showed a woman’s eye being subjected to the scalpel wielded by a male hand, Collier presents a cropped image of her choosing, which is carefully placed within the splicer’s tongs. In this work, the artist controls the image in a very detached, neutral way, and this method of working remains present throughout her oeuvre.

Who is Anne Collier? This is a question that will hopefully be answered by the first major solo museum exhibition of her work at the MCA Chicago from November. Curated by Michael Darling, the exhibition presents over 40 works dating from 2002 to the present-day. Though Collier has exhibited extensively internationally, her work has not been exhibited on this scale before. For Darling, it was a recent studio visit where he saw a new maturity and clarity to her practice that prompted him to propose a solo show. Few works dating from before 2006 are included in the exhibition, for this reason.

Collier grew up in the 1970s and 1980s, a period very much defined by advertising: television was at its heyday and people and companies were increasingly aware of the importance of visual imagery. Record covers became as popular as the music contained on the records and sales surged. This influence can be seen in Collier’s work, with pop imagery – fashion, music, art – culled from advertisements and magazines, intertwined with real found objects. Collecting from thrift-stores, eBay, and the ilk, Collier re-presents and re-photographs these objects in an entirely new way. Set against a neutral studio backdrop, the tape-cassette all of a sudden becomes (in a very Duchampian way) an art-object. Collier does this with books, records, magazines, postcards, anything she can get her hands on. There is a sterile quality to the works after she gets her hands on them: they are far removed from the networks of distribution that they were produced for.

Collier lives in New York City, but her work is very much defined by her upbringing and education in California. As a student at both CalArts and UCLA in Los Angeles, she was exposed to the work and practice of leading west coast contemporary artists John Baldessari, James Benning and Christopher Williams, amongst others. Like Baldessari, Collier developed an interest in the detritus of an image-making society. Found photographs proved to be a goldmine of material. Whereas Baldessari will often reposition the photographs against one another, placing them in dialogue, such as with his 1986 work High Flight, Collier keeps the photographs as separate, “unique” objects mimicking the conditions of product photography. She succinctly describes her process and intent (in a 2011 interview with curator Alex Farquharson) as: “Like commercial photography, I’m interested in establishing an aesthetic clarity but at the same time, through the nature of the objects I shoot, I’m equally interested in creating a sense of emotional or psychological uncertainty. This tension – between what is depicted and the nature of its depiction – is central to my approach.” By framing the subject of her photograph on a white, plain background, she separates it from any references of meaning relying on the viewer to make their own assumptions and analysis. Darling cites this as her strength as a visual editor, her ability to cull excess and isolate that which is needed for the image to come to life.

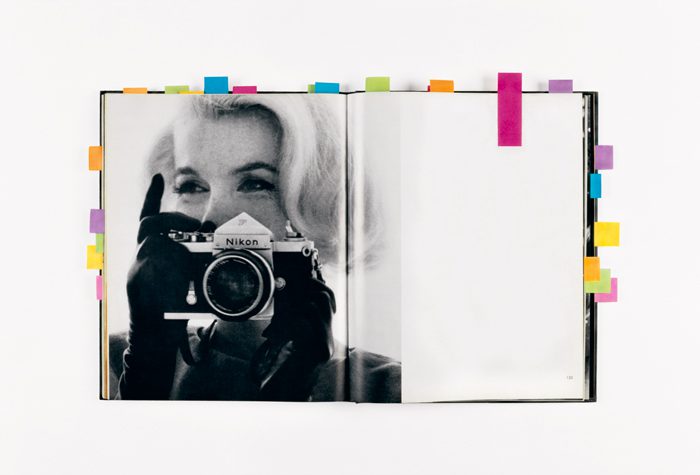

In one of Collier’s works, Zoom 1978 (2009), she photographs the front cover of that particular issue of Zoom magazine. The cover depicts a naked woman, seated, legs crossed, holding an exaggerated camera in her hands that completely covers and replaces her face. Here the female photographer quite literally becomes the camera. One can compare this with Collier’s iconic work Woman With a Camera (Diptych) (2006), where we see the photographed pages of film production advertisements for the 1978 film Eyes of Laura Mars. In the film, Faye Dunaway plays the title character, a fashion photographer who develops the ability to see through the eyes of a serial killer. In both of these works, in very distinct ways, Collier calls attention to the power of the photographer. Zoom 1978 makes such control clear: the historical image of the female nude disrupted by the placement of a camera over her face, the face being the unique signifier of her individuality. Zoom magazine was a pioneering French magazine, sub-titled Le Magazine de L’image, it presented novel, radical, articles and portfolios alongside one another. An issue from 1974 includes a series of distressing images of Vietnam by renowned photojournalist Philip Jones Griffiths, followed by a series of photographs of the sun in British advertising by Tony Evans, then a series of female nudes by Karel Fonteyne, and so forth. Collier’s choice of this magazine is deliberate: yes, the front cover image from the 1978 issue is powerful and visually engaging, but it is suggested that she chose it for the magazine itself, and what it stood for. There are layers of significance within Collier’s work that have yet to be peeled back, and this image provides a good example.

In Woman With a Camera, Collier is also highlighting the historical change of control from the typical “male gaze”, with the female character holding the camera. However, this is then subverted by the viewer’s knowledge that actually Dunaway’s character in the film poster is looking out through a male gaze. And Collier subverts this yet again by photographing the image in a female artist’s studio (hers) to be presented as an artwork. The presentation of stereotypical, sexualised images of women in a very neutralised, almost anthropological way, robs them of their psychological power. The images become a trope and now also become slightly amusing: we approach these hyper-sexualised images of woman in the same way that, for example, we now look at Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s 1767 Rococo painting The Swing with amusement. The Swing was considered to be highly erotic at the time of its creation, the young woman (Fragonard’s mistress at the time) with her ankle exposed, poised mid-air above her young lover below. We, as viewers, now approach Fragonard’s painting in much the same way as we now can do with an image of Marilyn Monroe, with her lips painted red and with tousled blonde locks, with full knowledge of the highly constructed methods of production, and the social and gendered politics that all went into its making.

Collier’s work firmly stands out in an art historical lineage of feminist art. Taking as an example Cut (Color) (2009), the ruptured eye delicately placed between two blades of a paper cutter, reminds the viewer of the sliced eyelids of Gina Pane’s Psyche (1974); the nicked, bleeding fingers of Marina Abramović’s Rhythm 10 (1973); and Yoko Ono’s highly charged performance Cut Piece (1964). Collier’s works are removed from these performance pieces, by the very fact that one does not see an act performed, but it is implied. The viewer knows it is a photograph of Collier’s eye, so is not a literal rendering of the slicing of an eye, but the trauma represented still shows the same intent: control over the artist’s body. Collier takes this further, as the eye represents the viewing device (the camera) and through its destruction, she destroys the idea that the camera can be a controlling device over the female subject.

The relationship between camera and subject is fraught with issues, that Collier tries to neutralise through her photographic method and simultaneously accentuate. This paradox is manifest through the presentation and manipulation of her subjects in the studio. Darling argues that she has an “amazing ability […] to document these objects that she finds in the world in the most neutral, hands-off, kind of dead-pan way, and yet these objects really come to life and can be interpreted in all kinds of ways.” One method of achieving this is by playing with scale: by producing photographic prints that belie the actual size of the object or image she is photographing. Placing posters, magazine covers, cassette tapes, and record covers on plain, flat surfaces in her studio, she photographs them from above so there is very little depth to the resulting image. In a interview with MoMA curator Eva Respini, Collier says: “Scale is very important to me […] adding a subtle layer of meaning to something or thinking about how not to just re-create the original object”. Collier, however, is not completely separate from the objects; she plays with them, often drastically physically altering them, as with the 2005 work Despair. Here we see a photograph of the tape cassette rent asunder with the ribbon pulled out into a frenzied pile: despair visualised.

Despair comes out of an earlier series, Introduction, Fear, Anger, Despair, Guilt, Hope, Joy, Love/Conclusion (2002), which consists of eight cassette tapes each of which is labelled with one of these titles, and then enclosed in a vacuum-formed plastic box. Do they contain a step-by-step audio guide to dealing with and understanding these issues? Perhaps – but Collier leaves it open-ended and ambiguous by denying the viewer the ability to listen to the tapes and discover their contents. We only have the pristine photograph of the object as a starting point in order to navigate through the implied meanings. Collier returns to this idea with the 2011 work Questions, which consists of a series of five photographs of open manila folders, each revealing a sheet of paper stating a topic and raising various queries. Collier found the folders on the street in New York City and they show their wear, slightly torn pieces of coloured paper with the text in an almost child-like large black font. As an example, one of the sheets has as its heading Connection, and lists the following: How are things, events or people connected to each other? Where have I seen this before? What is the cause and what is the effect? How do they “fit” together? These questions are so relevant to Collier’s oeuvre that it is disconcerting to find them posed within one of her own photographs.

Collier’s upbringing in California was as much defined by the artists she studied alongside and under, as well as her own personal history. The title of the work Jim and Lynda (2002) is meaningless unless you, as a viewer, know that these are her parent’s names, and that both are now deceased. The passing of her parents (her mother when she was five, and her father 20 years later) was understandably traumatic for Collier, leaving her orphaned at a relatively young age. Jim and Lynda (2002) is a visual memorial to her parents, presenting two views of the horizon of the Pacific Ocean, off the coast of LA, where their ashes were scattered. The still, calm image of the water and sky becomes laden with emotion through knowledge of this back-story. Darling argues that in Collier’s work there is a strong warring duality between the personal and impersonal: “There is a fierce distance, or neutrality, so even though you may intuit some of her back-story in some of these pictures, especially of ocean scenes or emotional states, she’s also really not trying to lead the observer to any kind of interpretation of the work.”

Knowing her past, it can be easy to pigeonhole some of the works as being highly emotive or laden with meaning. The image of a naked woman walking out alone into the ocean, her back to us, in California Poster (2007), evokes a range of emotions and thoughts: melancholy, despair, sadness, surrender. It is a powerful picture that sums up many concerns and sentiments in a very existential way. However, the reading of the photograph in this way is apposite to what it was intended for: the image it was originally an advertising poster for California from the 1970s, but here we read it as a melancholic picture of a solitary woman stepping out into the void. Through the isolation of the shot, and its subsequent reproduction, the artist is able to critique the historical reading of images. This legacy of “viewing” is a key theme explored throughout the exhibition, as it reinvigorates our own ability to read photographs, and sees Collier offer us a new approach to looking.

Anne Collier runs from 22 November through to 8 March 2015. Please visit www.mcachicago.org/media for tickets and further information.

Niamh Coghlan