The concept of the Internet as we know it can be traced back as far as the late-1960s. It’s tricky to say when it truly began, but most timelines cite 1989 – when computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee came up with the idea of the World Wide Web (WWW) – as a key milestone. Then, on 30 April 1993, CERN freely released its source code to the public. The aim, as displayed on the first ever webpage, was “to give universal access to a large universe of documents.” This concept – of a global platform for information exchange and communication – is the basis of Internet_Art: From the Birth of the Web to the Rise of NFTs, a new book by author, curator and broadcaster Dr. Omar Kholeif.

Key to understanding this volume is to grapple with what the art form is, and what it isn’t. Just this week (3 April 2023), news pages are abuzz with headlines about controversial AI image-generators and the impact they might have on the future of human creativity. It’s easy to get caught up in the noise, and even to dismiss all things digital. Yet, for Kholeif, “internet art isn’t necessarily art for the computer or even art about the computer. Instead, it is art that is produced with a knowing awareness of the networked nature of our collective culture.” It’s with this in mind that Kholeif embarks on their 30-year survey.

Internet_Art is, much like its subject matter, jam-packed with information. What’s more, Kholeif, who currently serves as Director of Collections and Senior Curator at Sharjah Art Foundation, UAE, imbues the account with autobiographical snippets from the art world. The result is an accessible and enjoyable experience; it feels like Kholeif is your personal guide on a fast-paced voyage through time and cyberspace. The content in Internet_Art is thorough, comprehensive and up-to-the-minute. No stone is left unturned.

Early chapters survey the premonitions of video pioneer Nam June Paik (1932-2006) – who envisaged so-called “electronic superhighways” back in 1974. By 2006, MySpace would become the most visited website on the planet, connecting users instantaneously and bringing this vision to life. Fast forward to 2021 and the creation of what Kholeif describes as “the pinnacle of a form of internet art”: Heather Phillipson’s (b. 1978) RUPTURE NO 1. The glowing installation comprises an array of physical objects alongside looped video screens, engulfing the viewer in red light. For Kholeif, this proliferation of things, sounds, shapes and colours matches perfectly with “the infinite scroll of the World Wide Web.”

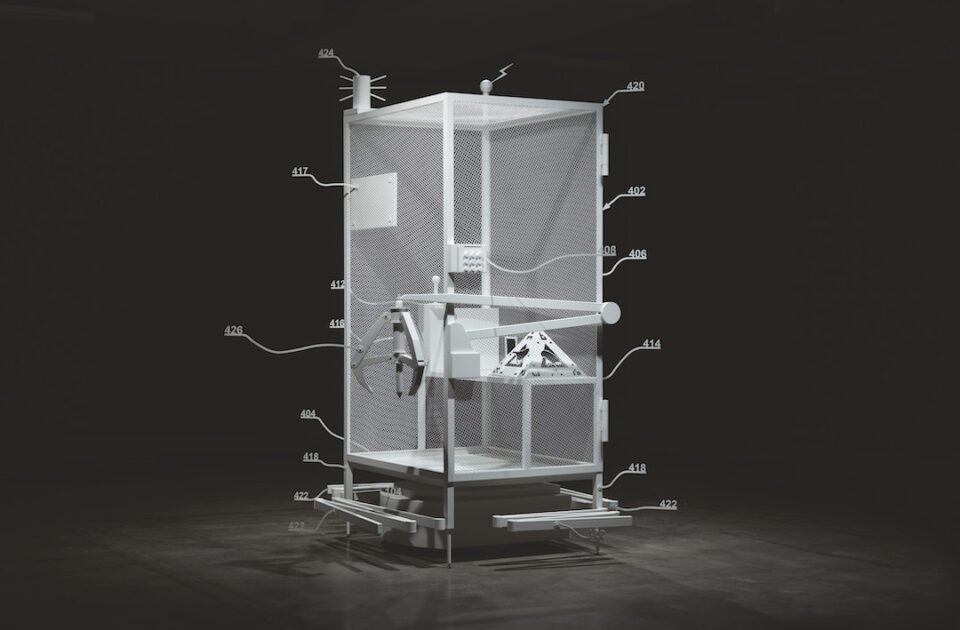

Elsewhere, we meet artists like Trevor Paglen (b. 1974) who are embracing the internet age with a critical eye. In 2013, Paglen documented – and subsequently released to the world for download – aerial images of the US National Security Agency and its associated architectures of mass surveillance and control. Then there’s Simon Denny (b. 1982), whose Amazon “worker cage” brings digital consumerism and labour relations into focus. Internet_Art closes on the Metaverse and Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s (b. 1985) AirPressure.info (2022), a website and interactive database which details the unlawful entries by planes, drones and unmanned aerial vehicles into Lebanon’s airspace. Like much internet art, it occupies a place where creativity, politics and activism coalesce, made possible by vast networks of cables connecting us.

Words: Eleanor Sutherland

Image Credits:

1. Guan Xiao, Sunrise, 2015. Picture credit: courtesy the artist. KraupaTuskany Zeidler, Berlin (pages 190-191) Car tires, artificial plants, exhaust pipes, light box, installation: c.189 × 62 1 ⁄4× 15 3⁄4 in. (c.480 × 158 × 40 cm); light box: c.59 × 157 1 ⁄2 × 15 3⁄4 in. (c.150 × 400 × 40 cm); object in the back: c.47 1 ⁄4 × 29 1 ⁄2 × 105 7⁄8 in. (c.120 × 75 × 269 cm); object in the front: c.23 5⁄8 × 23 5⁄8 × 30 1 ⁄4 in. (c.60 × 60 × 77 cm); edition of 3 + 2 AP

2. Heather Phillipson, RUPTURE NO 1: blowtorching the bitten peach, 2021. Picture credit: Photo: Tate. Courtesy the artist. © Heather Phillipson. All rights reserved, DACS 2022 (page 206) Video and sculptural installation. Installation view: Duveen Galleries, Tate Britain, London, 2021

3. Simon Denny, Amazon worker cage patent drawing as virtual King Island Brown Thornbill cage, (US 9,280,157 B2: “System and method for transporting personnel within an active workspace,” 2016), 2019. Picture credit: photo: Jesse Hunniford/MONA. Courtesy the artist; Altman Siegel, San Francisco; and Petzel, New York. (page 152, top) Powder-coated metal, MDF, plastic, digital print on cardboard, iOS augmented-reality interface, 115 3⁄8 × 87 3⁄8 × 99 5⁄8 in. (293 × 222 × 253 cm)