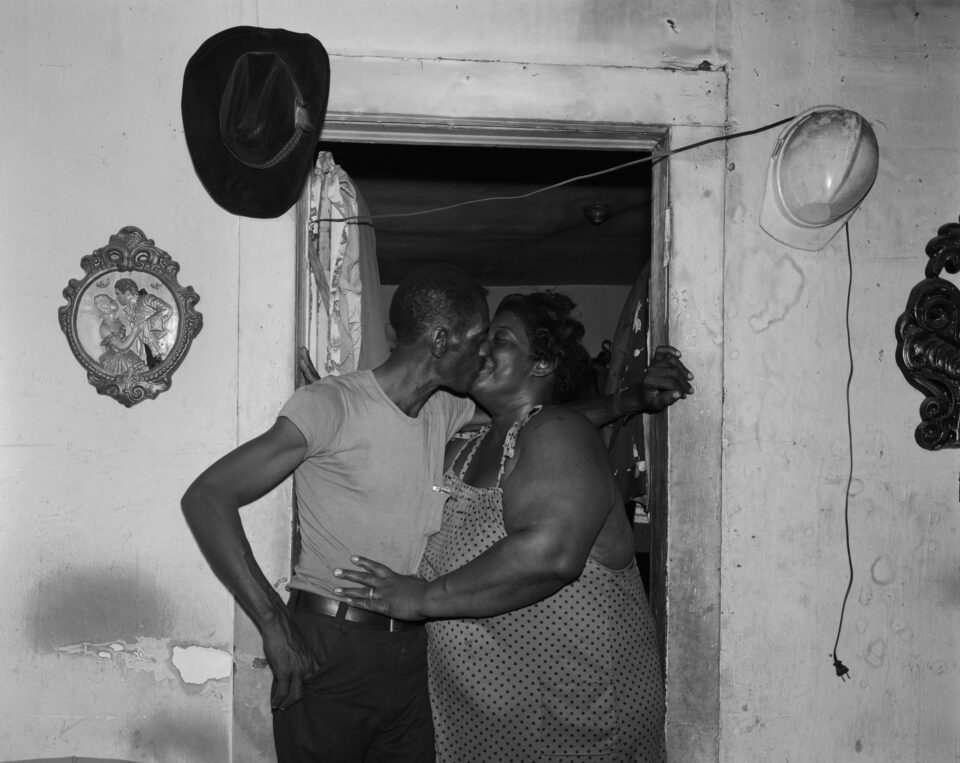

In 1983, photographer Baldwin Lee (b. 1951) left his home Knoxville, Tennessee, and set off on a 2,000 mile road trip into the American South, documenting the lives Black Americans at home, work and play. After almost four decades since the original journey, the artist’s work is finally being exhibited. The current exhibition, A Southern Portrait, 1983-89 at David Hill Gallery includes many previously unreleased photographs. Lee’s images depict the simple pleasures of childhood, the lives of working adults, and the bonds within families and communities, all reflecting his unique commitment to portraying life in America. Here, the photographer speaks to Aesthetica about his practice, influences and image-making process.

A: You have previously compared image-making to sculpture or theatre. How do you see the relationship between subject and photographer? Should both individuals be considered equal players?

BL: The reference to sculpture arises from my admiration of Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne in the Borghese Gallery in Rome. This work showed me the significance of gesture, expression and grace. Likewise, theatre highlighted the art of directing – an essential skill in portraiture. The relationship between subject and photographer is complicated. The issue of permission is the first impediment, especially in a case where neither party knows the other beforehand. Establishing a rapport requires a willingness to reveal as much about oneself as the subject is asked to reveal. Practically, the physical nature of the tripod-mounted camera – and its requirement for the subject to be still – demands that the shot be posed. I believe that posing is unsuccessful if it is evident. Successful posing persuades the viewer that neither the photographer nor camera were present. Both partners share equally in the process and product.

A: You’ve also mentioned that “looking is a two-way street.” How does the gaze of your subject inform your pictures?

BL: Gaze is the gateway to the interior world of the person in the portrait. It can lead the viewer to believe that they share an intimate knowledge of the subject – the kind of knowledge that has to be earned.

A: The details of your images feel so important: cowboy hats hanging from doorways; a Diana Ross album balanced on top of a television; clean white laundry drooping between deck posts. These elements make for intricate, specific shots. How important is the personal?

BL: If gaze tells you who someone is, then details tell you how a person lives. As in the case of a wonderfully presented meal, the details are important. The sculptural plating of the food, its size, shape and proportions relative to the serving vessel matter. The material, weight and design of the silver has to be considered. These elements enhance the experience, providing context, specificity and insight.

A: In Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning, poet and writer Cathy Park Hong writes, “Asian Americans inhabit a purgatorial status: neither white enough nor black enough, unmentioned in most conversations about racial identity. […] When I hear the phrase “Asians are next in line to be white,” I replace the word “white” with “disappear.” What abounds in A Southern Portrait, however, is a sense of presence. How do you configure presence and space in your work?

BL: A sense of presence arises not from disappearing but rather from achieving invisibility. I like to cite Flaubert’s dictum: “an author … must be like God in the universe, present everywhere and visible nowhere.” It serves no purpose to focus a spotlight on oneself when it should be aimed at the world outside.

A: You studied under esteemed photographer Minor White (1908-1976) at MIT and subsequently Walker Evans (1903-1975) at Yale. How did the artists influence your practice?

BL: Minor White alleviated the smothering weight of science and technology during my undergraduate experience at MIT. As a role model, he convinced me of the possibility of being an artist. I printed many of Walker Evans’ most important photographs while studying with him. His influence revealed itself immediately, and, eight years after receiving my MFA, I retraced his steps. I attempted to replicate his Greek Temple, Natchez, Mississippi (1936). I was stunned to learn he employed complex camera movements to convey a literary – not visual – meaning. I then understood his demand that his photography be “literate, authoritative and transcendent.”

A: In your interview with Aperture, you comment that you discovered you were “a political being”. Do you think photography is a political act? Does your body of work tell a particular story?

BL: It may be argued that all acts are political – that no action is without repercussion. But this is not to mean that one has to act politically. Goya’s Disasters of War, for example, did not cause warfare to end. That said, all photographs tell a story. The best pictures tell stories that are knowing, provocative, unnerving and touching.

A: You took an estimated 10,000 photographs between 1982 and 1989. You stopped taking pictures in the mid-1990s. What made you stop, how did you know it was the right time?

BL: I stopped for several reasons. One was shame. Toward the end of my seven-year project my expectations had changed. Ambition had become my master: I demanded successful photographs. At the end of a long drive through Georgia my pulse began to race as I saw a one-armed man pushing his lawn mower. I slowed my car to take a picture, but I didn’t get out because I was appalled at what I had become. I was physically and emotionally drained; I absolutely knew I had done my best work.

Baldwin Lee – A Southern Portrait, 1983-89

David Hill Gallery | Until 22 July

Interviewer: Chloe Elliott

Credits:

1. Baldwin Lee, untitled, circa mid-1980s

2. Baldwin Lee, Baton Rouge, Louisiana

3. Baldwin Lee, Marion, Arkansas, circa mid-1980s

4. Baldwin Lee, untitled, circa mid-1980s

5. Baldwin Lee, Vicksburg, Mississippi, 1984