In November 1944, the German administration banned photography in the Netherlands. It was a response to the Nazi regime’s growing precarity in WWII – Allied advancement and resistance activity were both growing by the day – and the prohibition of cameras was a way to prevent intelligence gathering and maintain tight control of the media narrative. Despite the climate of danger and repression, 14 photographers, alongside couriers and dark room assistants, worked in secret to document the occupation. They intended to smuggle the images to the exiled Dutch government in London, offering a stark account of the last months of German rule and, as a result, encourage food drops. These efforts, carried out at great personal risk, preserved a crucial visual record of this era. Now, Foam Photography Museum Amsterdam commemorates these courageous figures in The Underground Camera, an exhibition that reflects on the power of photography. The show is a tribute to the enduring legacy of these lens-based practitioners: their pictures not only served as a tool for exposing suffering and demanding action in their time, but continue to resonate today as a reminder of how history shapes the present. The museum’s curators, Claartje van Dijk and Hripsimé Visser, sum this up perfectly: “It is important to know history, to realise that without this spirit of resistance autocratic regimes may take the lead and destroy our societies.”

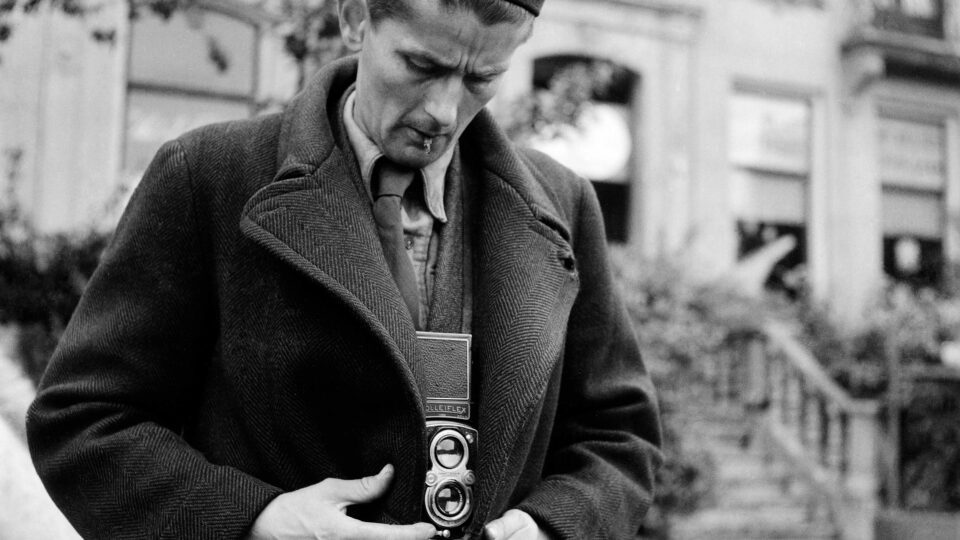

The photographers came to be known as The Underground Camera, which is where the exhibition gets its name, operating largely out of Amsterdam during the “Hunger Winter” of 1944 – 1945. It followed the Nazis blockade of food supplies after railway workers went on strike, hoping that halting transport would stop the movement of German troops. By the time the country was liberated on 5 May 1945, an estimated 20,000 people had died of starvation. Much of what is now known about this bleak period is thanks to the work of this group of photographers. They captured life in any way they could, frequently concealing their lenses in handbags and jackets to take pictures unnoticed. Many used Rolleiflex cameras, which had a viewfinder on top, making it easier to work from hip height. The resulting snapshots are haphazard, tilted and uncentred, the consequence of a hurried attempt to catch a moment undetected. It was an opportunity for the photographers, many of whom were politically active before the conflict, to play their role in the war effort. Van Dijk and Visser explain: “Many of the photographers were already involved in anti-fascist activities before the war, so we are also talking about a political mentality here … it is important to remember that that there was an organisation behind the images and two people who led the resistance group. There were many other illegal shots taken in the Netherlands during the war, both by amateurs and professionals, but this group is rather unique because it represents a careful planning of subject matter and outstanding photographers.”

The leaders behind The Underground Camera were Fritz Kahlenberg and Tonny van Renterghem. Kahlenberg was a German-Jewish filmmaker who had migrated to Amsterdam in 1933, whilst van Renterghem was a military professional. He trained as one of the Netherlands’ last mounted cavalry officers, before serving in the Armed Forces against German paratroopers. The duo instructed the group from their main location at the Michelangelostraat 36 in Amsterdam South. Under their guidance, 12 people took to the streets, camera in hand. These figures included artists who achieved great acclaim after the end of WWII, their teeth cut on the most harrowing of subject matters. Jewish photographer Emmy Andriesse worked in reportage before she was forced into hiding upon Nazi-occupation of the city. She used a forged identity card to reengage with public life, documenting the poverty and misery of everyday people. Cas Oorthuys’ work with various resistance groups saw him arrested and imprisoned in camp Amersfoort. He began working with Kahlenberg and van Renterghem upon his release, and his picture of a woman eating an insubstantial piece of bread became one of the group’s most famous. The figure’s haunted eyes are difficult to forget, glazed with hunger and loss.

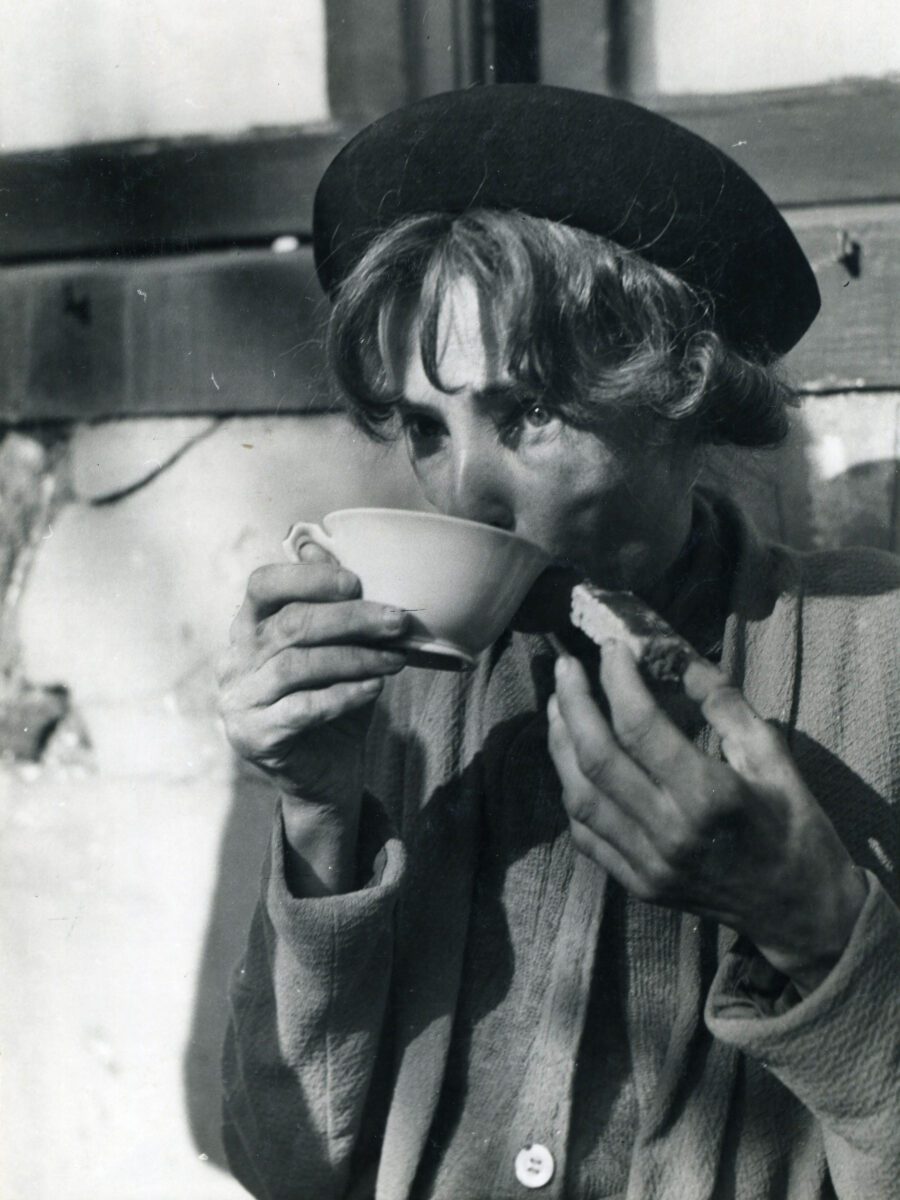

Foam’s exhibition consists of many arresting shots like the one taken by Oorthuys. Several highlight the impact of starvation, refusing to shy away from the effects on the young, elderly and vulnerable. Marius Meijboom captures a woman sipping from a teacup, a small piece of food in hand, whilst Emmy Adriesse focuses her lens on children, often startlingly thin and grasping empty bowls or cups. Elsewhere, the artists boldly document glimpses of defiance on the streets. Another of Oorthuys’ works depicts the words “Verzet! Verzet!” – meaning “Resist! Resist!” – painted in block capitals on a wall. Charles Breijer records a man climbing through the back of a cupboard, presumably to a space that hides clandestine operations or individuals who would otherwise be taken by Nazi soldiers. Van Dijk finds these shots to be particularly poignant: “There are many that I find extremely moving, like the children photographed by Emmy Andriesse or the images Charles Breijer took of hiding weapons in a baby carriage. One of the best photographs, in my view, was taken from a high vantage point by Ad Windig, showing how people took away wood for fuel from empty houses belonging to deported Jewish owners.”

It was only a few weeks after Dutch liberation, in early June 1945, that a selection of works from the resistance photographers went on display at the Keizergracht in Amsterdam. It brought national recognition to the members and marked the moment they officially adopted the name, The Underground Camera. Their photography, which revealed immense suffering, was emblematic of the psychological and moral reckoning that was happening across the world. The heroic efforts of covert resistance fighters came to light, marking them out as a force that helped turn the tide of the war, whilst Allied nations and civilian populations began to discover and confront the full extent of Nazi atrocities. The months after WWII officially ended were an agonising awakening, as society began to contemplate the type of world that would emerge from the ashes. The legacy of the conflict left its mark across Europe, and in 2025, we continue to see its impact. It is a particularly fitting detail, then, that Foam’s exhibition takes place along the same canal as that very first show, 80 years later. In taking up the same physical space, viewers are reminded of the proximity of history, and the lessons that need to be learnt to ensure it is not repeated.

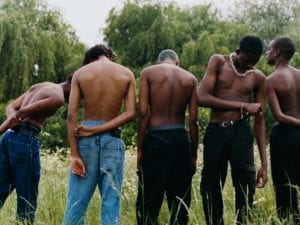

The Underground Camera was created in close collaboration with NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies. The organisation is an international centre of expertise for interdisciplinary research into the history of world wars, mass violence and genocides, including their long-term social consequences. The partnership is a clear testament to Foam’s commitment to presenting historical documents with the reverence they deserve, providing sensitive, honest and thorough context. The exhibition is also the first photographic collection to be included in UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register, which seeks to both preserve and promote documentary heritage that is deemed of significant importance. The display is part of Foam’s wider efforts to shines a light on the role of lens-based work in times of conflict. Recently, it launched the first solo showcase of the Palestinian-Dutch Magnum artist Sakir Khader. In Yawm al-Firak, Arabic for “Day of Separation”, Sakir Khader gives a voice to seven young Palestinian men who were violently taken from life, and to their mothers who lost them. Through their stories and experiences, the artist reflects on farewells in times of conflict, displacement, occupation and war. The Underground Camera is a vital reminder of the essential role photography plays in bringing injustices to light and ensuring that history, and the courageous figures who shaped it, are not forgotten.

The Underground Camera is at Foam, Amsterdam until 2 October: foam.org

Words: Emma Jacob

Image credits:

Cas Oorthuys demonstrates, shortly after liberation, how he took illegal photographs during the occupation, 1945 © Charles Breijer / Nederlands Fotomuseum.

Resistance slogans on a bunker Kwakersplein, Amsterdam, 1944-45 © Cas Oorthuys / Netherlands

Fotomuseum.

Hunger © Marius Meijboom, NIOD.

Illegal photo from bicycle bag of Kriegsmarine command post, taken from Emmaplein de

Emmalaan, Amsterdam, 1944 © Charles Breijer / Nederlands Fotomuseum.

Two women on their way back from a hunger march, early 1945 © Cas Oorthuys / Netherlands

Fotomuseum.

A man collects material from a demolished building, Zwanenburgstraat, 1944 © Cas Oorthuys

/ Netherlands Fotomuseum.