The word Endling was first published in 1996 by the scientific journal Nature. It was used as a way to describe the last known individual member of a given species – like Lonesome George, the final Pinta Island tortoise, who made headlines when he died in 2012. Once an endling passes away, its species becomes extinct. The expression has since been adopted in popular culture, including recent video game release Endling – Extinction is Forever, which describes itself as an an “eco-conscious adventure.” Most recently, it formed the title of contemporary artist John Gerrard’s (b. 1974) exhibition at Pace Gallery, New York. Gerrard is best known for creating “Land Art in the age of Google Earth”: eye-catching digital simulations examining timely issues related to energy production, food systems, climate crisis and the information age.

A: On 19 July 2022, the UK experienced its hottest day on record. Heatwaves are sweeping Europe. Your recent work, Flare (Oceania), explores the threat of warming oceans. Can you tell us more?

JG: Flare (Oceania) (2021) emerged out of my meeting with Tongan artist and activist Uili Lousi at COP25, the UN Climate Change conference in Madrid in late 2019. Francesca Thyssen Bornemisza brought my work Western Flag to Madrid and worked with her organisation TBA21 to place it upon a large LED in front of Museum Thyssen Bornemisza. I met Uili in front of the work and it was there he outlined that, whilst the subjects of Western Flag were of interest – those of CO2 legacy and histories of oil exploitation – he wanted to make a public declaration that “The Ocean is on Fire.” By this he meant that the world’s oceans are absorbing between 80%-90% of the excess heat societies are trapping through their emissions – resulting in a major global heat sink. And the ocean is heating fast. As it warms, it has more energy to spin out as catastrophic storms, in particular in the Pacific, damaging sea life, fisheries and, of course, causing water levels to rise. All of this seriously threatens the core viability of a low-lying ocean nation such as Tonga. I went away and thought for some months as to what I should do with such a statement from Uili – that the ocean is burning. Over time, I began to consider the idea of the flare, which has a layered meaning in English – to “flare off” gas for instance – often from an ocean oil platform – or alternatively to release a flare if lost at sea. I began to look at different flares and worked up a burning fuel simulation with the core production team of Werner Poetzelberger and programmer Helmut Bressler. The imminent threat to Tonga as a viable nation state, its potential extinguishing, suggested that the flare could also take a flag form – but one which was unstable – so the gas flare tapers off and then explosively re-emerges. Overall, I began to think of Flare as a kind of alarm, a siren to speak loudly about the heating ocean. Working with Art of Change 21 and the Hunterian Gallery at the University of Glasgow, we brought Flare to COP26 and installed it upon a major LED at the University. Uili Lousi also came to Glasgow.

A: You have spent 20 years developing game engines. What sparked your interest in the software?

JG: There are two responses to this. Firstly, my interest in computing more generally emerged from the rave and house music scene in the UK and Ireland in the early-to-mid 1990s. I started my BFA at the Ruskin School of Fine Art in Oxford in 1994 and used to travel with friends to clubs in Manchester, Liverpool and London. At that time, a lot of electronic music was coming over from the USA and I remember standing in a vast club in Manchester packed with people dancing and wondering: if computing can do this to music and move the public so strongly, what will it do to art? I made a decision to use computers at the core of my work going forward. I also made a lot of work about the dance scene at that time, but my primary understanding was more to do with computing and culture.

The second response relates to my discovery of 3D scanning whilst I was an undergrad at the Ruskin. I came across the technology whilst surfing the early internet in Oxford University’s computer labs, which I had open access to. 3D scanning struck me as a new way to think about the image – a photographic record which is also sculptural. I called them “image objects” and thought they had the potential to pull together different worlds and mediums: sculpture, photography, theatre, dance – and in some ways histories of painting. I approached a company outside Oxford who made a 3D scan for me in around 1996. It was a portrait of a friend called Mary and when I went off to MFA at the Art Institute of Chicago, I took it with me. It was, however, very unwieldy – a dense point cloud of data and I struggled to work with it. Nonetheless, chasing the “image object” post-MFA, I pursued a Masters in Science in New Media at Trinity in Dublin and onto a residency at the Futurelab – part of Ars Electronica in Austria. During the MSc, people were talking about game engines. I went to Futurelab specifically to work in that space. There, finally, I was able to put the scan into an engine – that was around 2001 – so it took five years to take that step. As it happens, the scan was unusable in the engines of that time. We digitally hand built a set of portraits for my first show at The Gallery of Photography in Dublin in 2003. I think what struck me most was how time becomes a sculptural component within a game engine. The 2003 show included early experimental work, which sees a young man sadden over 100 years in real-time. To cut a long story short, I had some success showing One Thousand Year Dawn (Marcel), which sold in Miami in an edition of six in 2005. It allowed me to really dive into the medium outside of the institution, making simulations which the public – almost exclusively Americans at that time – collected. I have been working in the space ever since.

A: Your work has been defined as “Land Art in the age of Google Earth.” What do you make of this?

JG: I had a conversation about this with Donna de Salvo – originally curator at the Whitney and now at Dia. It was in Venice during the 2009 Biennial, where I had a collateral project titled Animated Scene. We put three simulations as projections into a huge boat shed on the island of Certosa. I worked with curator Jasper Sharp and RHA Projects from Dublin to complete this. These were titled Dust Storm, Oil Stick Work and Grow Finish Units. Each piece in some ways intersects with Land Art histories, but I think most directly Dust Storm (Dalhart, Texas) (2007) is relevant here. It derives from a single archival photograph, dating from the 1930s and depicting one of the legendary dust storms that ravaged the American midwest during that time, producing the Dust Bowl, as the region was subsequently titled. In the work, a virtual dust storm permanently looms on the contemporary landscape. Unfolding according to an autonomous and unscripted pattern, I always thought of it as a sculptural form – as a sort of social sculpture.

Alongside Dust Storm, Grow Finish Unit Near Elkhart, Texas (2008) stands as unique record of the extreme functionality to be found at the start of the industrialised food production chain, wherein the contract between farmer and farmed is reduced to a purely technical, almost contactless process. The sheds are virtual reconstructions of sites on the Great Plains of the western United States. They each house up to 1,000 pigs, and each is entirely unmanned and operated on a day-to-day basis by computer. A scene almost entirely without visible action, the only apparent movement is that of an autonomous wind that animates the surface dust on the effluent ponds in an ongoing and open way. Additionally, in a symbolic moment of exchange, every six-to-eight months a transport truck will arrive and pull up to each building, where it stands for one hour. This rhythm reflects the growth cycle of the pigs enclosed within the sheds: the animals are being loaded into the trucks to be transported for butchering. As in reality, at no point are the many thousands of occupants of the eight sheds visible under the sun, which relentlessly circles in a 12-month orbit of its own, giving ultimate definition to the span of the work. Grow Finish Units emerged after a visit to the Chinati and Judd Foundations in Marfa. The reflective, serial forms of 100 Untitled Works in Milled Aluminum found an echo for me in the minimal groupings of pig sheds. Tate did a feature on the related work titled Sow Farm some years ago which is relevant here.

A: What does the process of putting a simulation together look like? What data do you draw from?

JG: Typically they begin with a single image, often a found image, which provides a clue or key to the work. Then, I travel to the site of that specific image and produce a photographic record of the place. Western Flag is a good example of this approach. The process of putting a simulation together is so deeply involved and complicated, but a brief summary would be that a photographic / drone / 3D scan of a site such as Spindletop in Texas, where Western Flag is based, is assembled by the producer of the work – Werner Poetzelberger – and sent out to modellers to be rebuilt in 3D. Poetzelberger works closely on the construction of the virtual scene: a kind of artistic stage upon which all elements – be it oil derricks, oil storage tanks, the flagpole — are placed. Separately, programmer Helmut Bressler developed a volumetric smoke simulation incorporating fluid dynamics. We needed this, because the smoke flag in Western Flag did not exist – it had to be scripted and constructed from scratch. The piece emerged after a year, made by a team of around five working on different schedules. In other works, there is a motion capture or an animation aspect, which is very involved. We typically work with an external company – Arx Anima – who, led by Martin Hebestreit, do a beautiful job of integrating motion into the simulations. A final stage involves setting the world in motion across the year, with night and day cycles and seasonal change in light conditions. We have to design dawn and dusk conditions and cloudscapes.

A: Can you discuss some of the other works on show? Washington.stream is particularly interesting, with its focus on the sprawling 405 freeway in Los Angeles.

JG: Endling at Pace centred on three new works: Endling, Flare and washington.stream. The title emerges from a word I found some years ago, which describes the last surviving member of any species before extinction. I thought it was such a melancholy and timely word that it needed to be wider known. The endling in my show is the last known member of the American Passenger pigeons, who was christened Martha and died in 1914. She lived out her last days in a cage in Cincinnati Zoo and became something of a celebrity. What makes her story remarkable is that as recently as 1800 there were as many as eight-to-ten billion passenger pigeons. Woodland clearance to make farmland and extreme human predation on the mass nesting sites of the passenger pigeon brought about a population crash of unthinkable scale. Passenger pigeons, previous to oil, provided a good chunk of the fuel needed to build the emergent cities of New York, Chicago and Philadelphia. Fed to humans and pigs they were a key food source for an explosive human expansion in America. Martha exists in the show as a monochromatic simulation based on photographs from Cincinnati Zoo, alongside a photo scan from her taxidermy body that was shared with us by the Smithsonian. The bird endeavours to keep the orbiting virtual camera in her eye at all times, which produces an uncanny sense that she is scrutinising the public.

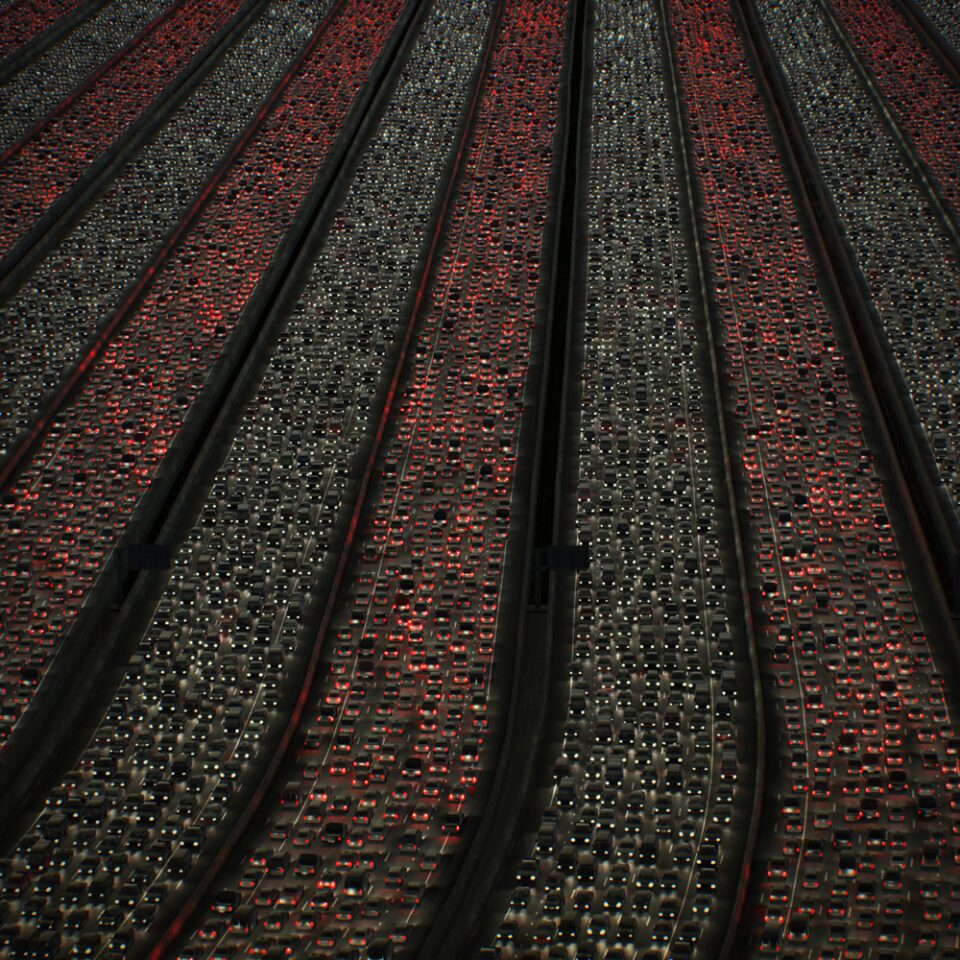

If Endling speaks of the past and histories of extinction, and Flare can be understood to be an alarm for a heating world, the piece titled washington.stream resides much more in the present. I found a new helicopter image online, taken during the Thanksgiving traffic on the 405 in LA. I was taken by the red stripe made by the car taillights on one side of the highway, and the white stripe made by the headlights. It was immensely American flag-like. The resulting piece remakes the highway as a virtual form, replicating it multiple times to produce a stage for a 30,000-car emotional traffic simulation. Each car operates as an autonomous agent and has different qualities: patient, angry, etc. Human behaviour patterns emerge from the long traffic jam – as cars inch forward in different ways. The piece is located in LA time, and a virtual camera orbits in the work as if attached to a news helicopter. The highway stripes of red and white light move from horizontal to vertical over about 30 minutes. I am specifically interested in how legislative decisions affect individual behaviour – fuel subsidies, motor car tax breaks, wider city planning and motorway building – and how all this adds up to a sort of national condition. washington.stream is also the domain name for the work online. In time, I will also make beijing.stream, in which all the cars travel the same direction – on a highway outside Beijing – and perform a red or white field of colour depending on the camera direction. Getting back to the Land Art question: I like how both works deal with scale and energy, but also have something of a subversive relationship to Californian traditions of light and space.

A: What do you hope audiences took away from the exhibition?

JG: In New York, we opened the front wall at Pace onto the street. Pretty much everyone who walked by stopped to look and often entered. Delivery guys parked their bikes and came inside. I am interested as to what a work like Flare can do for public consciousness: if it can move the people. In this technologically and media-saturated world, which I could not have imagined in 1994, there is value in producing and showing these kinds of anxious digital objects in the public domain, and to do so at scale.

A: Are you working on any new projects right now? How might the simulations develop going forward?

JG: In about six months we will begin to focus on what is called WebGL – or Web Graphics Language. It moves the game engine off a dedicated local PC and allows the virtual world to be rendered in the individual browser page online. This space is a core focus right now.

Words: Eleanor Sutherland

Image Credits:

1. John Gerrard, Flare (Oceania), 2022. © John Gerrard / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

2. John Gerrard, Corn Work, 2020. Galway International Arts Festival / Galway 2020 / Claddagh Quay, Galway. Photographer Ros Kavanagh.

3. John Gerrard, Solar Reserve, 2015. Art Basel.

4. John Gerrard, Western Flag (Spindletop, Texas), 2017. At Desert X / Coachella Valley, CA, USA 2019 @ Lance Gerber.

5. John Gerrard, Solar Reserve, 2015. Art Basel.

6. John Gerrard, Leaf Work At Galway International Arts Festival, 2020. Photographer Ros Kavanagh.

7. John Gerrard, washington.stream, 2022 © John Gerrard / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

8. John Gerrard: Endling, 510 West 25th Street, New York, NY 10001. June 29 – August 12, 2022 Photography courtesy Pace Gallery.