In 19th century America, there was a cultural belief that colonial settlers were destined to expand westwards. This idea was coined “Manifest Destiny”, with some early settlers considering the western regions of the US a wilderness to “tame” – a deeply problematic concept. It was a mythology which, despite conjuring new opportunities and horizons for settlers and colonisers, was devastating for Indigenous populations. French documentary photographer Patrick Wack (b.1979) became interested in this concept whilst living and working in China. He saw parallels between contemporary events in the country and those in the so-called “wild west” during the 1800s. Wack set out with his camera to explore whether China’s 21st century push westward mirrors events in America 200 years ago.

China’s Belt and Road initiative – a new-fangled iteration of the ancient Silk Road – begins on the far-western frontier of Xinjiang. The region has historically been linked with trade routes, acting as a crossroads for the movement of people, goods and ideas between Europe and Asia. It also represents one sixth of Chinese territory and is rich in hydrocarbons, mineral resources and virgin agricultural land. It is home to about 20 million people from 13 major ethnic groups, the largest of which is the Uyghurs, a predominantly Muslim community with ties to Central Asia.

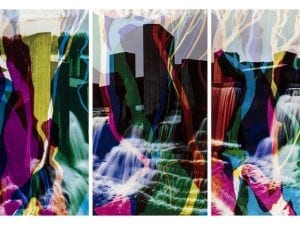

Wack spent two months in the region between spring 2016 and 2017. He produced Out West, a project that aimed to show the world a side of China that pushes past pre-existing media-driven stereotypes of a homogenised state. Using Kodak film, he chronicled the rocky sweeping landscapes – desolate and serene – the undulating hills set beside growing towns, and the buzzing cities, old towns, mosques and bazaars. He also photographed people, especially the Uyghur community, some of whom call China’s presence in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region – or East Turkistan – a form of imperialism. Out West showed a China divergent from images of modern Shanghai and its tall shiny buildings, or Beijing’s sprawling cityscapes and polluted sky.

With the project complete, Wack left China after 11 years and moved to Berlin.When news of internment camps in Xinjiang appeared in the mainstream media in 2018, however, he felt compelled to return to the region. Wack visited Xinjiang twice in 2019. He produced another documentary project, The Night is Thick, at a time when there were major restrictions in the region; photographers were followed and faced harassment. At times he was stopped and made to delete images from the camera, but the RAW files were saved on the memory card.

These two projects are compiled in a new photobook, DUST. 71 photographs and three texts bring context to the situation in Xinjiang. Two of the essays are by academics: Rémi Castets, a French expert on China, and Dru C. Gladney, an American anthropologist. There is also a piece by Brice Pedroletti, former China bureau chief for Le Monde. The essays cover the historical trajectory of the people of Xinjiang from the 18th century. They also cover China’s designation of the Uyghur Muslims as separatists and terrorists in the mid-2000s, and the situation of the Uyghurs in China today.

In late July 2021, Wack was caught in a social media storm whilst promoting pre-orders of DUST. Kodak posted some pictures from the book on their Instagram feed and Wack wrote an accompanying text calling Xinjiang an “Orwellian Dystopia” for the Muslim population. This led to wumao – hired internet trolls that push the Chinese Communist Party’s agenda – laying siege to Kodak’s post. It was subsequently deleted, with Kodak releasing a statement saying that they would “continue to respect the Chinese government.” “It shows two things of the current world we live in,” Wack says of the incident. “The power of social media and how everything around China is politicised.”

Wack was criticised for being an opportunist – that he hyped up the political situation in Xinjiang to sell his book. “I think Out West was not political originally,” Wack says. “When I was photographing the first project, I had no idea what was happening to the Uyghurs.” He also stressed that the aim behind the project was purely documentary. “I’m not a photojournalist. I’m not a conflict photographer,” says Wack, pointing out that this project very much fits the ethos behind Inland, the co-operative he cofounded. “We focus on long-term storytelling where we try and combine a documentary aspect with an artistic vision.”

One such photograph in DUST shows a body of teal-coloured water in the foreground. A rocky mountain range bisects the horizon and above it the cloudy dove-grey sky just covers the mountaintops. The three colour bands of varying widths have an abstract configuration – there’s something of Andreas Gursky’s digitally manipulated Rhein II about it. Gursky’s aim with editing his 1999 image was not to create fictions but rather to heighten something that exists in the world. Although Wack’s images have not been manipulated, they give a sense that something has been removed from the scene.

DUST by Patrick Wack, published by André Frère Éditions

The book is available on the publisher’s website, in bookstores around the world and via online retailers.

Words: Misha Maruma

All images fromDUST by Patrick Wack, published by André Frère Éditions.