“Climate grief” is a phrase that we hear more and more these days. It describes a psychological state: the dizzying combination of loss, anxiety, anger and sadness felt in the face of the climate emergency as it worsens. In 2021, a worldwide survey of 16 to 24-year-olds found that four in 10 were so afraid of the future, they were reluctant to have children. (Young People’s Voices on Climate Anxiety, Government Betrayal and Moral Injury: A Global Phenomenon, Lancet Planetary Health) This is surely a thoroughly rational response when you look at the facts. The 10 years leading up to 2019 were, on average, the hottest ever on record. Floods, wildfires, storms and many other extreme, life-threatening weather events are becoming increasingly commonplace, up 85% in the last 20 years. We have lost 70% of animal species in just under 50 years. There are plenty of reasons to grieve.

And yet this route into discussion of the crisis isn’t always the most helpful. “In our early stage workshops Will Skeaping from Extinction Rebellion introduced the idea of the ‘apocalyptic recap’,” says Caroline Till, co-founder of futures research agency Franklin Till. “You start by presenting the situation as it is – this is gravity of the damage we’ve done, isn’t it terrible before talking about what we need to do differently…” It’s definitely an important technique used to foster understanding of the situation. Cumulatively, however, this can have the effect of making people feel powerless, so overwhelmed that they ignore what’s happening – similar to the notion of compassion fatigue in photojournalism – that we reach a point where we become inured to images of suffering and look away in a state of apathy.

When Caroline Till and Kate Franklin came on board as guest curators to work alongside Barbican International Enterprises’ Co-Head Luke Kemp on Our Time on Earth, the team were intent on adopting a different strategy. “It’s important to have awareness of the scale of the issue, but it can be paralysing. We wanted to carve out a space to build a constructive way forward, spotlighting the ingenuity of art, design and culture to do that,” she says. They took inspiration from the American environmental activist Joanna Rogers Macy (b. 1929) who talks about this unique moment in history – the “Great Turning.” Instead of envisioning apocalypse, she speaks of “adventure.” She writes: “Of all the dangers we face, from climate chaos to nuclear war, none is so great as the deadening of our response.” A radical optimist for whom hope is a productive act, Macy argues nothing less than a complete transformation in consciousness will save us.

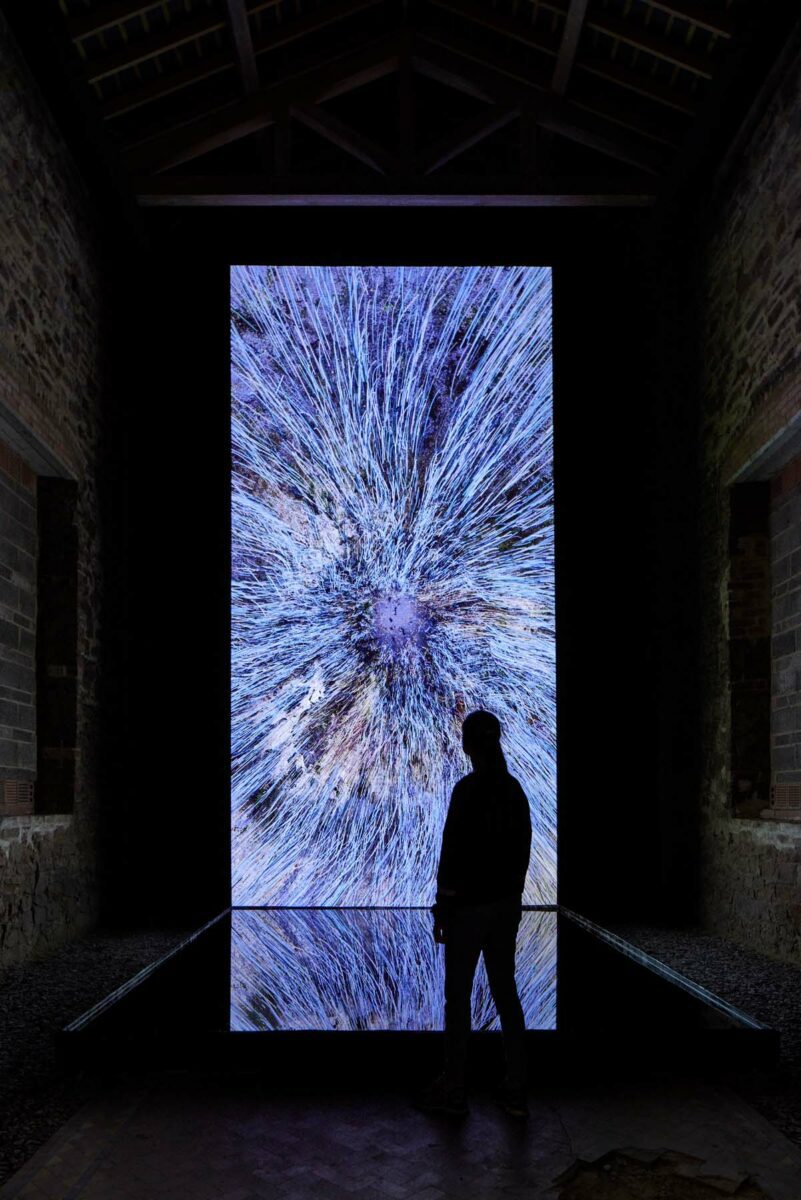

“We are completely interconnected to nature, we are nature,” says Till. “It’s not something that we own or control, a resource to extract from. In this exhibition, we want to stimulate a wider shift from the point of view which places humans at the top of a hierarchical model of nature. Instead, we propose a biocentric approach, where we consider humans as one of many species in this diverse ecosphere.” The curato- rial journey is therefore divided into three stages or “chapters” entitled Belong, Imagine and Engage. On entering the Curve – where the main exhibition is staged – visitors find themselves descending into a dark, cocoon-like space. The walls are covered in natural wool and forest green felt, “giving a sense of weight and warmth,” whilst an audio piece poses questions alternately and tunes them into the rhythm of their breath in a deliberately meditative process. At the bottom of the stairs is Sanctuary of the Unseen Forest, by Marshmallow Laser Feast and Bio-Leadership Project co-founder Andres Roberts, a 5.5m x 3m video installation taking viewers inside a tree.

Imagine presents 10 possible scenarios – all positive propositions for a future where we have managed to successfully avert climate catastrophe and, therefore, are able to live harmoniously within the natural world, having achieved true sustainability. Some of these pieces may seem speculative, such as Liam Young’s film Planet City – set in a time when lands stolen in imperial conquests have been returned and rewilded and the entire global population lives together in one giant, hyper-dense multicultural megacity – or Super- flux’s Refuge for Resurgence – which depicts a vast dining table where humans, animals and plants feast together (not on each other) – but these projects are all grounded in real research. “These 10 pieces are, indeed, very different in their approaches, but they all explore living system thinking – ac- knowledging what we can learn from nature,” says Till.

The ultimate chapter, Engage, marks a return to the present- day. In a collaboration between Kerala-based architecture company Wallmakers and the eco-focused creative agency The Earth Issue, this section offers 10 stories of change, showcasing activists around the world, many from the Global South, who are working to build a post-climate crisis world. Barbican’s Luke Kemp notes: “It’s a global issue so it’s crucial to show multiple perspectives.” A powerful example of this is a commission made by individuals from the Khasi com- munity of Meghalaya in North-eastern India, the Subak community of farmers in Bali and the Ma’dan community in Iraq, who worked with designer Julia Watson and engineer Smith Mordak, of Buro Happold, to showcase technologies that are thousands of years old, and which offer solutions for a sustainable urban future. Finally, the visitor comes across a sonic waterfall by Silent Studio, inspired by their work with Damon Albarn on the solo album The Nearer The Fountain, More Pure The Stream Flows. The feature uses red noise frequencies which have been proven to help with anxiety. “We didn’t just want to spit people out, but give them a moment to reset for the start of another journey,” adds Kemp.

It might seem surprising that digital technology is the means by which the exhibition seeks to realign humanity with the organic world. We have never been more alienated from nature, and in many ways, it seems that digital technology is to blame. Three quarters of English children spend less time outdoors than prison inmates (according to a 2016 governmental survey), whilst a 2019 report found that out- door play in green spaces had been replaced by screen time, which was up 50% in a decade (A Movement for Movement, Association of Play Industries). However, in Our Time On Earth, technology allows us to experience nature in a way that is more profound than what we could do in “real” life.

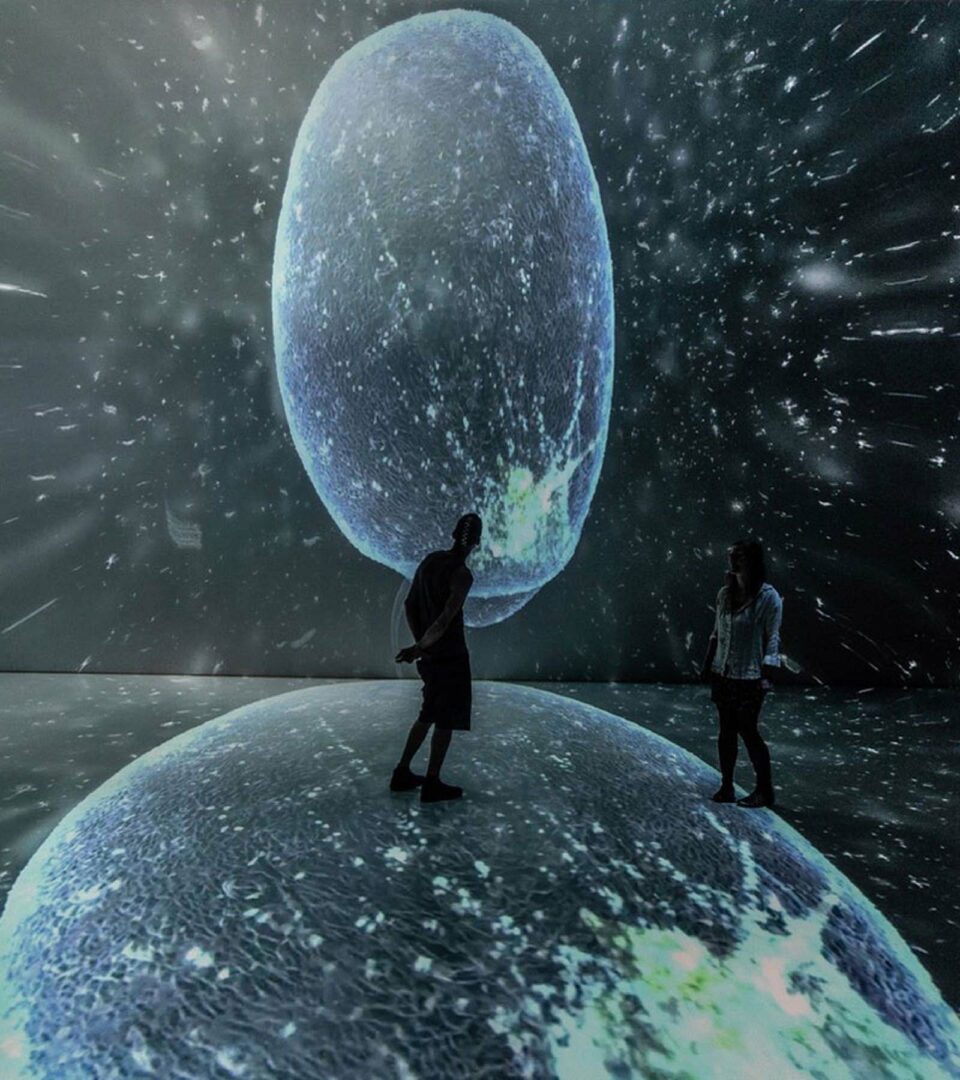

Noise Aquarium, an immersive installation by US artist Victoria Vesna in collaboration with Austrian scientific visualisation specialists, for example, places visitors in the sea, surrounded by plankton blown up to the size of whales, to feel what it’s like to experience noise pollution as they do. This is an encounter that isn’t a replication of what we find in nature: the experience allows us to go beyond what’s possible. As a result, audiences are able to identify and appreciate the significance of these miniscule organisms: creatures that, ultimately, play a vital role in oxygen production (with half of our oxygen coming from phytoplankton photosynthesis).

Like trees, these beings help us to respire – and to live. Barbican International Enterprises (BIE), the department responsible for the exhibition, was founded with precisely this remit – to programme digital-first, festival-style experiential exhibitions that showcase cutting-edge technologies and cultural phenomena. Previous shows have focused on virtual reality, gaming and AI. As the Barbican’s touring arm, BIE works with partner organisations to take shows around the world over three to five years. Our Time on Earth’s first stop will be the Musée de la Civilisation in Quebec City, Canada in 2023. “We look at big, meaty, zeitgeist topics that can feel unwieldy,” Kemp explains. The climate emergency was an obvious choice, but it also posed a challenge. Unlike AI technology, this subject has been covered extensively already, so it required a fresh angle. “We really had to ask ourselves, why bother? It was about doing it in our way, speaking to audiences who might not otherwise find it, offering multiple access points. We work on anything from music and architecture, to contemporary art, design and philosophy. And we wanted to give a sense of hope, achieved through creativity.”

Europe’s largest and most iconic arts centre, with its seamless Brutalist architecture, was conceived on utopian lines. This year, four decades since it opened, the Barbican has appointed a design team for Barbican Renewal, a project that will reconsider the buildings in light of the venue’s commitment to reach net zero by 2027. This sustainable ethos isn’t just about production, but also about curatorial choices. The 2009 blockbuster show, Radical Nature: Art and Architecture for a Changing Planet is a clear example. “Cultural institutions and museums can bring imagination,” says Kemp. “We’re don’t have all the answers, but we’ve got ambition.”

A crucial part of that is about commissioning. Of the 18 pieces on show at Our Time on Earth, 12 are new, many down to collaborations arranged by the show’s curators. Initially, for example, Kemp and the team had approached Guardian columnist and environmental activist George Monbiot on the subject of rewilding, but when the journalist pointed out that soil was one of the most undervalued natural wonders and should garner the same admiration as the Great Barrier Reef, they matched him up with innovation studio Holition to produce an installation that sends visitors underground. Similarly, the ideas of Colombian biologist Brigitte Baptiste – who argues that “there is nothing as queer as nature” – were given artistic form by the Institute of Digital Fashion, London. The project comprises a mirror-like experience whereby the visitor’s face fuses with that of other living creatures, express- ing the notion that fluidity, hybridity and adaptability are inherent to how plants, animals and humans evolve and thrive.

Interdisciplinarity is understood here as a grounding philosophy, and it is well-suited to the subject matter. Barbican demonstrates that, if we’re going to flourish in a post-climate emergency future, it will be through collaboration, collective solidarity and wholescale change – by mapping out new systems of eating, moving and existing, not simply by individuals remembering to bring their tote bags when they nip to the shop. “The shift in consciousness that we desperately need is already happening in some parts of the world. Indigenous thinking has been discarded as primitive [by the west] but it’s backed by science and buoyed by a growing aware- ness of stewardship. It’s the way forward,” says Till. There is hope, but there is also a sense of urgency. As she reminds us: “This is our window of time to be able to change course.”

Words: Rachel Segal Hamilton

Our Time on Earth, Barbican, London 5 May – 29 August

Image Credits:

1. Previous work by Marshmallow Laser Feast; Observations On Being, Coventry City of Culture 2021. Installation image of We Live in an Ocean of Air Video Edition. Photo by David Levene.

2. Liam Young’s Planet City on display at Our Time on Earth, Barbican, London. Credit: Liam Young.

3. Noise Aquarium, Laznia Gallery, Gdansk, Poland 2020 Credit: Victoria Vesna / Adam Bogdan.

4. Thijs Biersteker, Wither (2020). Courtesy of the artist.

5. Previous work by Marshmallow Laser Feast; Observations On Being, Coventry City of Culture 2021. Installation image of We Live in an Ocean of Air Video Edition. Photo by David Levene.