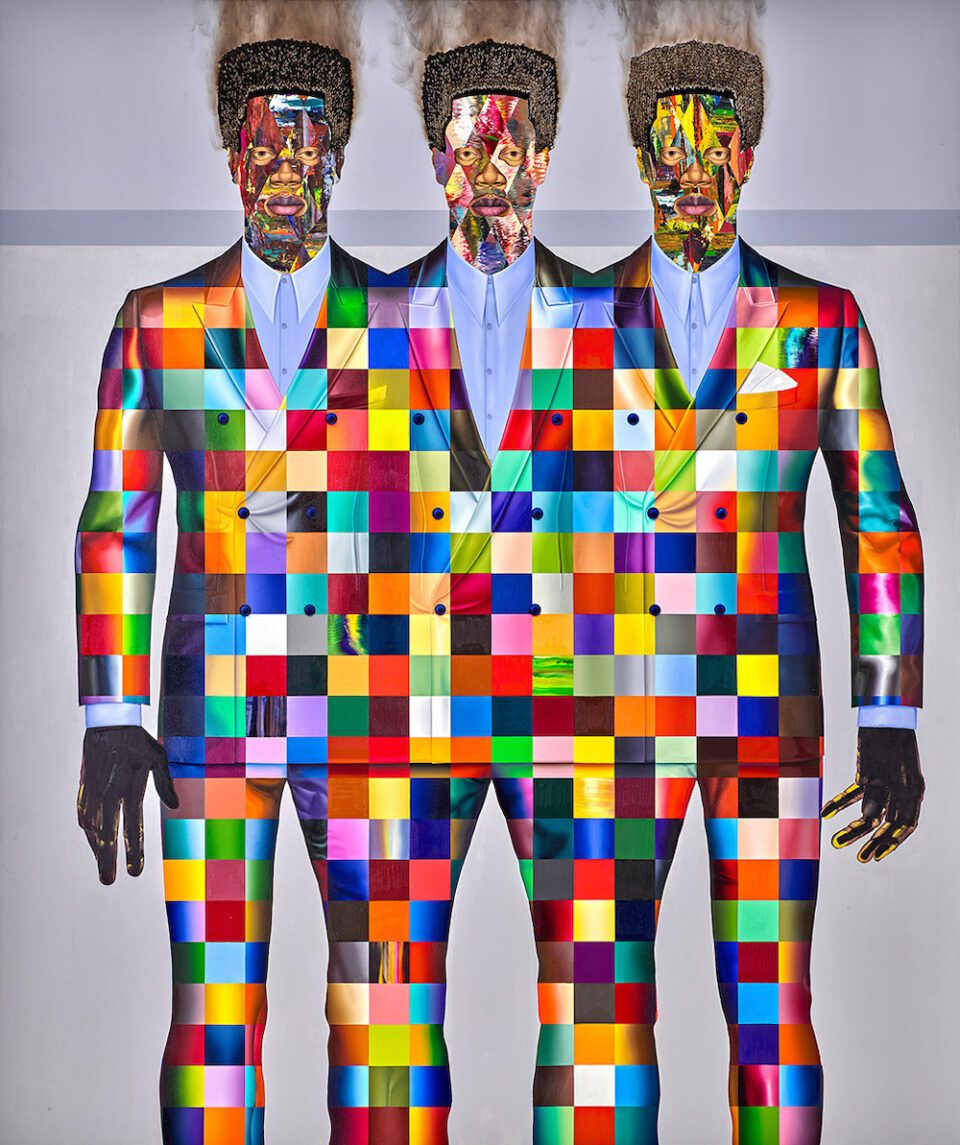

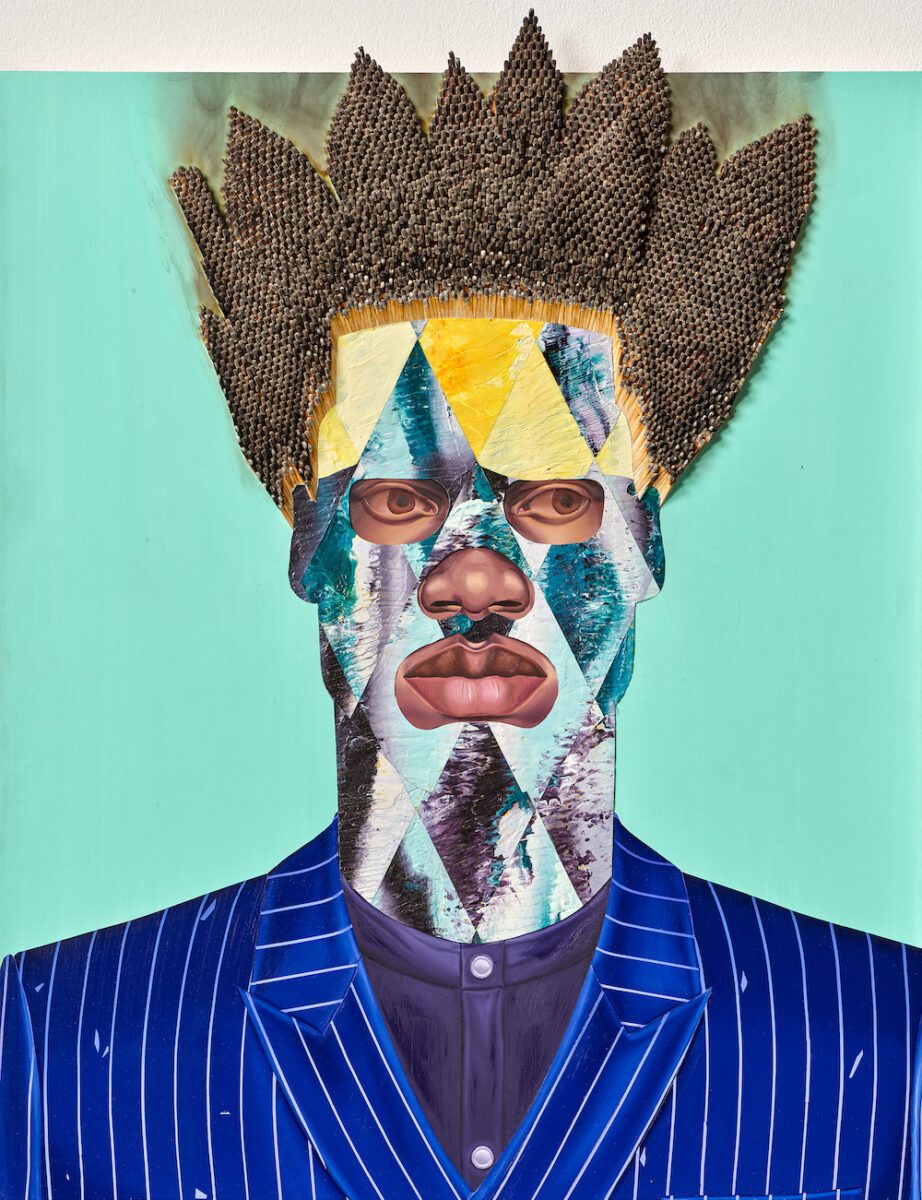

Electric colours. Lush backgrounds. Suits emblazoned with pinstripe, harlequin and grid patterns. These are works by Jeff Sonhouse (b. 1968), an American artist creating stylised portraits of Black male figures. His works challenge the conventions of traditional figurative painting, incorporating 3D materials such as matches, steel, copper and stones. In his busts and group portraits, elements of Western art history meet pages from contemporary men’s fashion magazines, photographs of Sonhouse’s friends and news imagery. This eclectic approach results in slick, eye-catching compositions – many of which are now on view at Zidoun-Bossuyt Gallery, Luxembourg. Aesthetica speaks to the artist about his vision.

A: Your works draw on, subvert and adapt the long history of portraiture, specifically in relation to representations of African American men. Why is it important to question the legacies of art history, and how do you approach this in your practice?

JS: I found it was vital to my creative practice to delineate what I learned at school from my personal experience, and to create representations of characters who embodied spirit, or possessed what would be seen as swagger to those I imagined capable of sensing it. This approach, I gathered, would distance my figure-centric paintings from those made by my contemporaries and painters that arrived before me. I mainly accessed art history’s legacy to avoid being accused of mimicking and not for revisionist purposes.

A: Your paintings are full of vibrant colours and textures. How would you describe your visual language?

JS: I would describe my visual language as one made up of attitude and materials.

A: Where do you find inspiration for your characters? Can you give some examples?

JS: Many of my ideas for characters are inspired by African, Panamanian and Caribbean folklore, as well as Black American culture. For example, the conjoined figures in my latest body of paintings developed from a film I saw in the 1970s. It’s titled The Thing with Two Heads, where a white man’s head is attached to a Black man’s shoulder. What I remember most vividly is how the figure’s movement was restricted. Today, I’ve adopted this figure to symbolise the individual – how they are affected physically and psychologically by the monolithic idea Blackness has now become.

A: Many of your works use collage – extending into the viewer’s space. Why do you choose to work in three dimensions?

JS: My assemblages and collage are what I use to lure the viewer in: encouraging them to examine, process and compartmentalise my work. It’s a technique I suspect they’ve never seen applied in a painting before. I thought of it as a way to avoid being ignored.

A: Recurring props and motifs – such as harlequin patterns – appear throughout your oeuvre. Is there a certain symbolism behind these elements?

JS: The harlequin pattern is symbolic of the Trickster: a protagonist found in Native American and African folklore. I associate his duplicitous character with Pablo Picasso, who made him a subject of many paintings. Picasso himself is a controversial figure – he’s been accused of appropriating African figurative sculptures in his painting. Both Picasso and the Trickster are subjects of contention; they embody a friction which I found made for good content.

A: What do you hope viewers take away from your work?

JS: I’d like the viewer to take away from my work the name Jeff Sonhouse – and whatever else they see fit.

Bodied runs at Zidoun-Bossuyt Gallery, Luxembourg, until 6 November. Find out more here.

Image Credits: All images courtesy Jeff Sonhouse and Zidoun-Bossuyt Gallery.

1. Raulo, 2021

2. One Man Gang, 2021

3. One Man Gang, 2021

4. Untitled, 2021

5. Augustine’s Mauvism, 2021