Frank Gehry, an architect responsible for some of the world’s most visually and technically outstanding constructions, is celebrated in a major European retrospective.

Canadian-American architect Frank Gehry (b. 1929) is best known for glimmering landmark structures such as the titanium-clad Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, the Walt Disney Concert Hall in downtown Los Angeles, and the Vitra Design Museum in Germany. While many of his best known works have materialised over the past 20 years, Gehry was an established architect long before he rose to prominence in the 1980s.

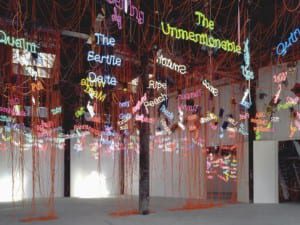

It was in Los Angeles, in the 1960s, that Gehry opened his own office as an architect. There he engaged with the LA art scene, becoming friends with artists of the Ferus Gallery such as Ed Ruscha, Richard Serra, Claes Oldenburg, Larry Bell and Ron Davis. At the time, a new art scene was emerging in California, influenced first by the hybrid materiality of Robert Rauschenberg’s Combine Paintings and the complex textures of Jasper Johns’s Flags and Maps, and then by the emerging Pop Art movement. Gehry’s encounters with this revolutionary scene and artists such as Rauschenberg and Johns would open the way to a transformation of his architectural practice, as his work began to mirror the great change that these figures had created in the art world.

Gehry does not teach and does not produce books describing his manifesto, so his working methods have not been broadcast perhaps as much as those of his contemporaries. This first, and long overdue, retrospective of Gehry’s work will therefore play an important role in revealing the architect’s process. As the exhibition’s curator, Aurélien Lemonier, explains, the exhibition intends to “be as close as possible to the conception of buildings, not in terms of process but where in his mind the idea or shape of the work has come from.”

To achieve this, the exhibition includes images of 60 finished projects alongside supporting documentation, numbering an astronomical 225 drawings, 67 models and a biographical film made by director Sydney Pollack, Sketches of Frank Gehry (2005). But why has it taken so long to chart the rise of one of our leading architects, whose LA practice was first set up in 1962? As Lemonier notes, Gehry is very much a forward-thinking man, and does not like the idea of looking back to the past, therefore the exhibition does not employ a linear chronology but instead is structured in six sections which combine to retrace the various stages and themes of his long career.

These segments – Elementarisation/Segmentation; Composition/Assembly; Fusion/Interaction; Tension/Conflict; Continuity/Flow; and Singularity/Unity, which encompasses Town Planning and Computer Tools – act to clearly discern the development of the architect’s visual, architectural and artistic language. Lemonier says “although we understand that Gehry has had a long career, we knew that the idea of a retrospective would be an argument,” so these six sections were included in the proposal initially sent to Gehry when conceiving the show. The curator recalls “we sent the proposal, discussed it with him, and two days later he said, ‘yes it works.’ It was simple like that.”

Further to breaking down the retrospective into thematic stages, Lemonier identified “urbanism as a good angle to take as a retrospective” and so the design of the exhibition is organised around two key strands: the idea of urbanism, and the development of new systems of digital design and fabrication. This is also timely, as the exhibition coincides with the inauguration of Gehry’s Louis Vuitton Foundation which, set in the Bois de Boulogne, and dedicated to contemporary art, has taken nine years and 30 new technical patents to build. Ten exhibition galleries divided into parallelepipedic blocks, the building alternates full volumes and open spaces beneath 3,600 clear glass panels which form 12 huge “sails,” each with a different curve which work to create a light-filled building within the 19th century Parisian park.

The Foundation epitomises Lemonier’s appraisal of the architect: the curator seeing Gehry’s work as displaying “an openness of the mind and liberty of concept,” proving that “it’s true that anything is possible, not like a game, but in terms of taking risk” and teaching young architects to be “free from very narrow doctrines.” This philosophy was of course encouraged by Gehry’s part in the vibrant 1960s LA scene, which was a time when he began to create his own signature architectural language through experimentation.

In fact, it was Gehry’s friendship with artist Jasper Johns that led to his pioneering use of architect and theorist Philip Johnson’s concept of the “one-room building” in an urban context. This idea, to have a building consisting of one autonomous space fascinated Gehry and was put into practice by him. He explains: “I was trying to figure out how to get to the essence, like my painter friends; what does Jasper think about when he makes his first gesture? The clarity, the purity of that moment is difficult in architecture.Gehry says: “When Phillip gave that speech, I said, ‘Ah ha; that’s it.’ The one room building could be anything, because it just has to keep the rain out, but there’s no complexity in it; functionally, that makes it do something.” As the architect notes: “That’s why churches are just one beautiful space.”

Lemonier says, “Gehry was taken by Philip Johnson’s idea and translated it into housing; the foundations of architecture became something about urbanism.” Due to his interest in urbanism, Gehry began to build “villages” of one-room homes: series of autonomous spaces, a multiplicity of monofunctional buildings, which avoid the effects of monumentality, are easily varied in scale, and accord with the minimalism and unity of Gehry’s larger structures. Where Johns’s work may have inspired the one-room building, the materiality of Gehry’s work bears strong resemblance to the artwork of Rauschenberg or the structures of Serra. Despite the fact that Gehry’s clean, clear glass constructions hardly appear “poor”, his career began with a strong interest in utilising “poor” materials such as cardboard, sheet steel and industrial wire mesh, of which he has said, “if you play with it, you can use it and make things, as Rauschenberg did with the combines.”

Gehry further explains: “I worked in my grandfather’s hardware store and so I made pipes and we cut glass, and we had nails and putty, and I fixed clocks and all kinds of things. I always had this tactile reference of some kind.” Whilst his most recent works use a range of materials, they continue to avoid stone, and incorporate wood, steel and mesh on a monumental scale.

Gehry was first attracted to the work of these influential artists – Rauschenberg, Johns and Oldenburg, with whom he collaborated on the Vitra Design Museum – as he “didn’t feel comfortable with the patterns that were being developed architecturally” at the time. He goes on to say: “I love Rudolf Schindler, I loved what was going on, but I didn’t want to copy it.”

Gehry is a complex and in some ways contrary individual, working as an architect almost in protest at the current trends in the field rather than in accordance with them. He explains that “from the beginning, I never liked buildings, except if I saw Frank Lloyd Wright or Schindler, or something, of course…I don’t know why, I started looking at the spaces between buildings … Once I started doing that, I was pretty interested.” His works are characterised by valuing the void as much as the structure, and consistently pushing the boundaries of construction. To explain this methodology as part of his role as curator, Lemonier chose to include original process models from Gehry’s California studio: “We visited Frank Gehry’s storage in LA and looked at an incredible number of models and chose those that are most expressive in terms of process. We didn’t want to include any presentation or competition models.”

There is, however, one competition model included, which was created to gain the commission for the Walt Disney Concert Hall. In Gehry’s signature style, the façade of the building is a series of sweeping stainless steel curves, containing one of the most acoustically sophisticated concert halls in the world and with much of the site dedicated to public gardens. Gehry’s structures are intended to be experiential spaces, targeted towards providing a mass audience with an entirely enveloping experience. His first commissions of the early 1960s included artists’ studios, home and town planning, and his buildings have even transformed the economies of the cities in which they stand – his Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao being a prime example of architecture’s capacity to revive and regenerate its surrounding economic fabric. He is as concerned with urbanism as he is with the integrity of any single building, explaining this directly during his interview with Sydney Pollack for Sketches of Frank Gehry, by questioning, “How do you make architecture human?” “How do you find a second wind after industrial collapse?” These questions, surrounding a broader urban vision, have run through and set the course of Gehry’s work over several decades.

Since his “villages” of the late 1970s and early 1980s, the architect has continued to work in the field of urban planning, as detailed in one of the exhibition’s final sections, Town Planning. This section includes lesser known works which truly reveal aspects of the architect’s personality and attitude towards the urban environment. There is the Alameda Redevelopment (1993) in Mexico City, which was simultaneously a densification and a refurbishment of an abandoned zone in Mexico’s historic district; the Central Business District (1981) Michigan – a plan to develop two existing basins into a commercial centre and residential district, and whose heterogeneousness emphasised Gehry’s aim to produce as much diversity as possible within the city – and the Nationale-Nederlanden Building (1992-1996) Prague, Czech Republic.

This latter commission was originally simply to build an office block; however, from the initial sketches – which are being exhibited at the Pompidou alongside the preparatory models – emerged a greater idea, a concept which would aim to unify the surrounding landscape with its architecture.

Comprising two towers with curved profiles, the building completes the row of buildings stretching along the river and mirrors the water below; meanwhile, its two elements interact with one another like the bodies of two dancers, leading the architect to nickname the project “Fred and Ginger.” It is evident that Gehry has an emotional connection to his buildings, and the addition of the film Sketches of Frank Gehry within the retrospective provides Gehry himself with an active and animated voice at the heart of it. Lemonier explains that the film was chosen for the exhibition for this very reason, as “it gives the personality of Gehry to the show, and makes it more alive – it’s fascinating how people watch so carefully. It’s very important to see how he speaks; this work is not just the conceptual idea of architecture, it is very physical and material, which Gehry explains very well.”

While the exhibition looks at Gehry’s use of new technologies alongside the urbanism that leads his work, his working practices are surprisingly traditional. He is famous for his hand drawings – hundreds of which are included at Centre Pompidou – and describes the computer image as “lifeless, cold, horrible.” Meanwhile, he also admits, “I still rely on the model technique for building because it’s my hand directly on the thing. When you use only the machine…and you get a 3D model, a 3D print, it’s totally impersonal and scary.” This is fascinating for an architect whose constructions are so incredibly high-tech; however, it demonstrates Gehry’s interest in tactility and materiality.

What emerges from the exhibition is the way in which Gehry’s buildings combine an interest in the character of urban life, artistic and historical influence, with an understanding of light, materials and space, and a disregard for conventional limitations. The architect asserts: “What I look for in history are the human touches, what happened because of the technology that was there, and then try to say, ‘We’ve got new technology, we’ve got new things, so how do we not lose the past?’” This enquiring mind-set has led to some of the most dramatic and imaginative architectural constructions of recent history, and this is explored in depth this winter at the Centre Pompidou.

Frank Gehry’s first major retrospective in Europe continues at Centre Pompidou, Paris, until 26 January 2015 www.centrepompidou.fr.

Chloe Hodge