Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph, offers a comprehensive survey of a pioneering body of work. Born in Detroit but based in New York since the early 1970s, Ming Smith was the first female African-American photographer to have her work acquired by New York’s Museum of Modern Art. She has mastered a blurry, impressionistic style emulating the mixture of spontaneity and detail in the jazz music she often evokes with her images.

Raised in Columbus, Ohio, Ming Smith’s childhood unfolded in a setting very different to the Manhattan and Brooklyn streets that she made her own (this book contains a striking image of Smith as a child, on her first visit to New York in 1959, looking out of a window with innocent fascination). Shortly after settling in the city she became, in 1973, the first woman member of the Kamoinge Workshop, a collective of black photographers, which, as Yxta Maya Murray notes in one of several accompanying essays, “gathered at each other’s homes on Sundays to discuss racial discrimination within the American Society of Magazine Photographers and critique members’ work.”

In 1979, MOMA purchased two of Smith’s photographs (she stunned the purchasing curator by initially hesitating over the low price offered). But this was followed by a long period of relative quiet, during which Smith raised a family and, according to M. Neelika Jayawardane, remained “largely invisible to the white art establishment.” A resurgence of interest can be traced back to an LA show in 2000, gathering to a crescendo over the last few years with a retrospective in New York and the inclusion of Smith’s work in important group shows at the Tate Modern and Brooklyn Museum.

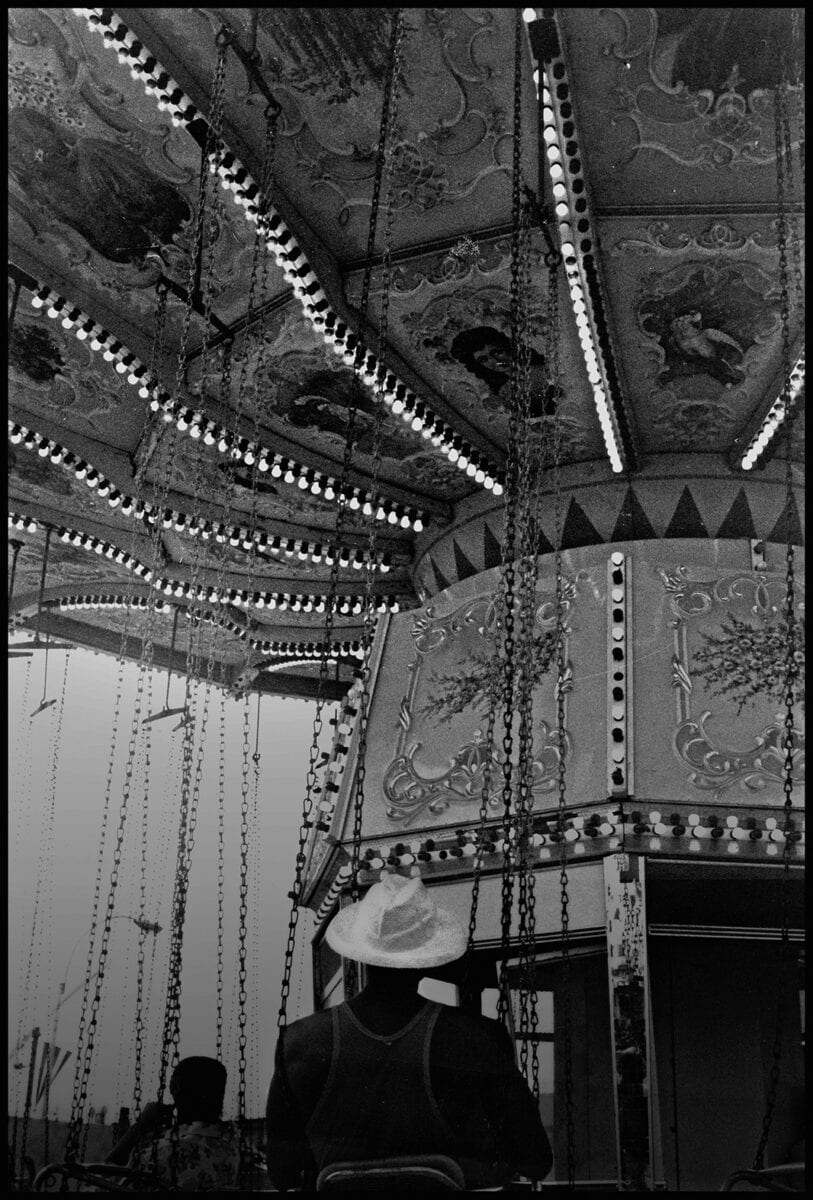

Ming Smith’s photography demonstrates both style and substance. Known for her use of slow shutter speeds and levelling of foreground/background distinctions, the artist imbues her images with a kind of improvisatory fuzziness which belies her attention to figurative and textural detail. According to the cinematographer Arthur Jafa – an admirer of Smith’s work, whose interview with musician and writer Greg Tate towards the end of the text is a highlight– Smith’s style expresses a “super Black” energy that emulates the pointillist precision of free jazz.

Jafa adds that that the way Smith’s camera seems to dance around its subject speaks to the historian Robert Farris Thompson’s theory of the “natal African traditional context of viewing artefacts”, in which – as Jafa puts it – “the artefact moves around the viewer as much as the viewer moves around the artifact. And that dual movement produces a blur.” Whilst one appraisal of Smith’s work might place her in the company of Monet and the Post-Impressionists, then – whom she cites as influences, and whose spirit we can certainly sense in her extraordinary over-painted photos of the last few years – this doesn’t seem to be the primary or most useful frame for her pictures.

This is certainly the case when it comes to subject-matter. There is an attempt here to capture what Jayawardane calls “the sacredness of ordinary black life.” Images of Brooklyn and Harlem from the 1970s, such as What’s It All About?…, Amen Corner Sisters… and Jump… (all 1976)have the anecdotal quality of polaroid snapshots but, perhaps for that very reason, convey an extraordinary intimacy. There is an implication of personal connection between subject and photographer, related to the informal staging, and the sense that Smith is physically moving around the scenes she relays. Alongside anonymous models, there’s also a persistent focus on late 20th century icons and lodestars, including writers (Amiri Baraka, James Baldwin), dancers (Alvin Ailey, Judith Jamison), and, above all, musicians: Sun Ra, Pharoah Sanders, and Smith’s former husband saxophonist David Murray, who appears in the wings at a show in Padua, Italy, in one muted but luminous image.

There is also anger at play here, with many images being powerful for leaving much unsaid. For example, in Bicentennial Celebration (1976), two black children in their weekend best half-heartedly clutch American flags behind a crowd control barrier. Other works, such as America Seen through Stars and Stripes, takes on the violence done to black culture more frontally, red daubs of paint forming an enveloping miasma of blood or flame around a black male portrait.

Attempts to pigeonhole Smith as a documentary photographer of African-American experience would be misguided, though. For a start, her camera has a wandering eye. There are shots here of West-African cultures – Senegal, Ivory Coast – in which Smith becomes the observer. In making her images of Dakar and Senegal, she recalled: “somehow it seemed that our cultures are very different, but we are very much connected. In some ways it was like returning home.” Then there are the shots of Egypt, Ethiopia, Japan; street kids smoking cigarettes in Portugal; hippies in Paris; an elderly white couple square-dancing in Smith’s native Ohio.

On top of this, Smith is, at least in one of her guises, a kind of jazz photographer, whose combination of technical dexterity and apparent spontaneity emulates the musicians she so often photographs – perhaps above all the polymath grandfather of Afrofuturism, Sun Ra. In Smith’s Sun Ra Space II (1978),he seems to be wearing a cape of intergalactic light, a gathering of bright white points marked out against the gloomy interior background. The mixture of fine detail and fuzzy sprawl in Smith’s image is the perfect homage to the composer’s wild but virtuosic musicality. Or, to rework a phrase from Emmanuel Iduma’s essay, it is as if, through Smith’s photographs, “the eye can see music.”

Find out more here.

Words: Greg Thomas

Images:

1. Ming Smith, Self-portrait, ca. 1988, from Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture/Documentary Arts, 2020) © Ming Smith, courtesy the artist and Aperture.

2. Ming Smith, West Indian Parade, Brooklyn, 1973, from Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture/Documentary Arts, 2020) © Ming Smith, courtesy the artist and Aperture

3. Ming Smith, Instant Model, Brooklyn, 1976 (from the series Coney Island) from Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture/Documentary Arts, 2020) © Ming Smith, courtesy the artist and Aperture

4. Ming Smith, Coney Island Detailed, Brooklyn, 1976 (from the series Coney Island) from Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture/Documentary Arts, 2020) © Ming Smith, courtesy the artist and Aperture

5. Ming Smith, Sun Ra Space II, New York, 1978, from Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture, 2020/Documentary Arts, 2020) © Ming Smith, courtesy the artist and Aperture