Ridley Scott’s film adaptation of Blade Runner came out in 1982. It’s since become the blueprint for high-tech, neon-soaked dystopia and cyberpunk aesthetics: cities emblazoned with colourful billboards and 24-hour artificial light. Six years prior to its release, Canadian photographer Greg Girard (b. 1955) arrived in Tokyo. “Blade Runner-esque” had yet to enter the lexicon, and he was soon entranced by this modern, futuristic city. Girard quickly turned his lens on the city’s people and glowing nocturnal architecture. Now, this largely unseen collection of images is published in a new book: JAL 76 88.

A: The book begins in April 1976, with you setting out to spend a few days in Tokyo.

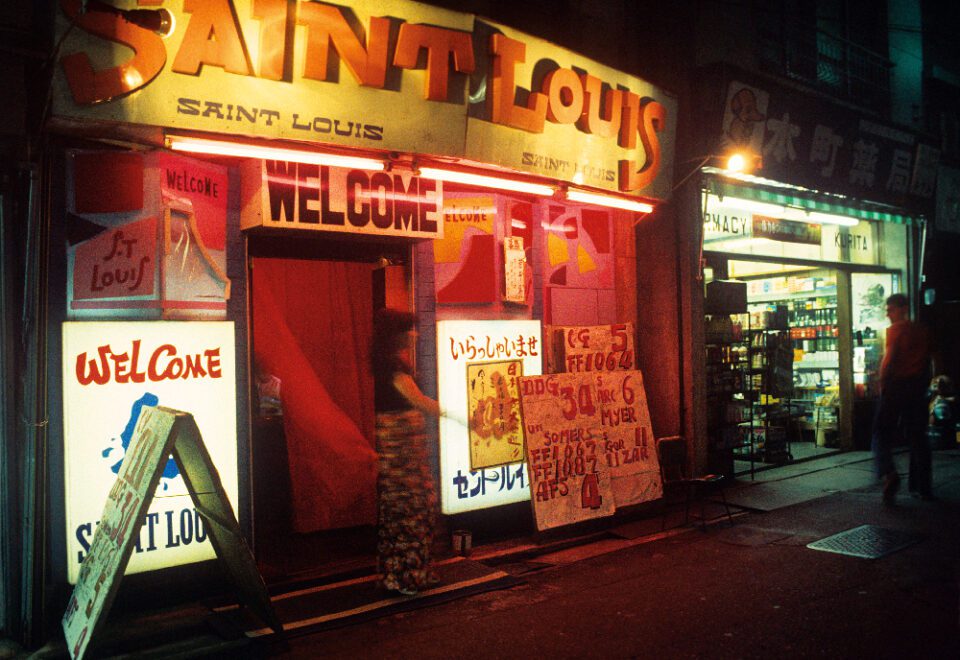

GG: I’d booked a one-way ticket to Bangkok with a stopover in Tokyo, intending to stay only a few days and store my luggage at Haneda airport. Night was falling as I took the train into the city. I rode the loop of the Yamanote line around Tokyo, and, after arriving in Shinjuku for the second time, I got off the train. It looked like the liveliest part of town. I spent the night wandering around, drinking coffee and taking pictures, and by morning I knew I wanted to stay. There was, of course, that initial fascination of a new place. Of seeing somewhere you’ve heard about, thought about, and realising it’s nothing like you expected. Things might sound more or less the same if you used words like “buildings” and “cars” to describe them, and yet everything looked and felt completely different. The world I knew started to slip away.

A: Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner came out in 1982, becoming a leading example of high-tech, neon-soaked dystopia. Looking at your work in 2022, how do feel your images sit within that conversation?

GG: Arriving in Tokyo in 1976, there was nothing that prepared you for what you were about to experience. It simply wasn’t known that a neon-soaked, high-tech, off-kilter version of the future already existed in an Asian city. Blade Runner hadn’t appeared yet, and (to paraphrase William Gibson) TIME magazine hadn’t done a cover story about the city yet. The notion that Japan was a modern, urbanised society hadn’t really registered in the West. The spectacle of Shinjuku is alluded to early in Blade Runner – in the giant video billboard advertisement. I was thrilled to see modern Tokyo sampled and extrapolated into a Japan-inspired urban future. That was something completely unprecedented.

A: Many of the shots depict TV screens, windows, billboards and signs. Others capture streets under darkness, illuminated by glowing lights. How did you decide what to photograph? What drew you to capturing the city at night, for example?

GG: I had worked at night right from my earliest pictures. It was a natural progression to be out wandering around Tokyo at all hours. I photographed the neon and the entertainment districts, but also the “ordinary” neighbourhoods and less glamorous parts of the city – concentrating more and more on the latter as time went by. I think it’s fair to say I photographed everything. By which I mean there wasn’t really anything, in terms of subject matter, that couldn’t be a photograph. A television screen is perhaps a good example.

A: In the late 1970s, these photographs brought visions of a modern, futuristic city to the US. What was the reaction like at the time?

GG: These images didn’t have any sort of audience until decades after they were made. I didn’t start working professionally as a photographer until late 1987. I first posted this series on my website around 2010. Some was published in one of my early books, but it wasn’t until very recently that these pictures of 1970s and 1980s Japan were shared as a dedicated body of work. So, really, they’ve hardly been seen at all.

A: JAL 76 88 demonstrates the “social and physical transformation of Japan before and during the Bubble Era.” Can you tell us some more about the socio-political and economic backdrop of the book?

GG: By the time I arrived in Tokyo, the West was already accessible there. Magazines followed what was happening in London, Paris, New York and elsewhere – across fashion, music, cinema and other areas of popular culture. Yet to those in the West, Japan appeared much further away and relatively inaccessible.

The country, however, was about to become a global player. Its consumer electronics and cars soon came to be viewed as equal – or superior – to western products. As the relative value of the yen increased, Japanese corporations went on a global buying spree. The growing disposable income of Japanese consumers sent many out travelling and shopping. It was something of a shock for the West.

My early years in Japan as an English teacher were pretty much hand to mouth, photographing in my free time. In 1988 I returned to Tokyo for a magazine, with an assignment to document Japan’s new ascent. The view of the city shifts – looking out from the high floor of a good hotel, for example, in comparison to earlier scenes of cheap rooms and street-level views. It’s not spelled out as such in the book, but some of that lingering post-war scruffiness, still evident in the 1970s, starts to disappear by the 1980s.

A: Information didn’t spread as quickly back then – there was no Instagram, Twitter or Google Maps. How do you think JAL 76 88 will resonate with contemporary audiences, who are used to the fast pace of digital? Why publish it now?

GG: I first discovered photography in print – in magazines and books – so I’m biased. But I do know there is an audience who appreciates what a printed collection of images can do. Books present a world between their covers. I don’t think it’s ever really a choice between on-screen and print. Each does something very different. As for ‘why now?’, it probably has something to do with downtime during Covid. I’m working on a new project in Japan, but haven’t been able to visit. I ended up spending time looking through my archive.

A: The book features a combination of colour and black and white compositions. Is there a distinction for you between the two formats – in terms of the subject matter you choose, or the atmosphere you want to evoke?

GG: I used to carry two cameras, one with black and white film and one with colour slide film. I chose one or the other according to some now-forgotten instinct, and I was always drawn to photographing in colour at night, right from the start. Mostly on a tripod, doing long exposures under artificial light – whether neon, or fluorescent or sodium vapour street lighting, or some combination of them all. One attraction to using black and white film during that period was that I lived not far from a darkroom rental facility, and so I could do my own printing in a closet-sized space in my neighbourhood.

At this time in the West, there was a kind of residual conceit that serious photography meant black and white. Colour was considered a comparatively commercial and crass medium. Fortunately, I didn’t study photography formally, otherwise I might have been impacted by this nonsense. Tokyo was bursting with the most amazing “commercial” photography in ads, posters and on billboards, as well as features and ads in magazines. The distinction between commerce and art was either blurry or non-existent, or differentiated in a way that wasn’t clear to me. Museum-quality shows were held on the top floors of department stores, and photographers exhibited their work in camera manufacturer galleries, like Nikon Salon or Canon Salon. This lack of distinction was perhaps best on display in the great Japanese camera magazines of the day, titles like Camera Mainichi and Camera Asahi, as well as the many fashion magazines that were pushing boundaries in ways the West would later come to appreciate and borrow from. The world is a more interconnected place now. Tokyo has been transformed by the way we’ve come to know it in recent years: by films, anime and other cultural exports, and by seeing it for ourselves.

All images courtesy Greg Girard, from JAL 76 88.