Artist and filmmaker Derek Jarman (1942 – 1994) once declared: “Oh how Shakespeare would have loved cinema!” The artist’s 1984 film, The Angelic Conversation, combined slow-moving footage of two men exploring their sexual desires with a reading of 14 of the Bard’s Sonnet. Shot on Super-8 before being transferred to 35mm film, the unique approach roots the project firmly in the avant-garde movement of the 1980s. Associated with the New Romantics, filmmakers used contrasting colours heightened to achieve a highly processed but luxuriant look. The work is reactionary, challenging both the decade’s austerity and its entrenched homophobia. The Angelic Conversation embodied Jarman’s staunch commitment to raising awareness of AIDs and advocating for LGBTQIA+ rights. The profile and platform that came with success was dedicated to campaigning against Clause 28, a law which prevented homosexuality being taught in schools. Jarman himself passed away from AIDs-related illness in 1994, leaving a legacy of creative innovation and boundary pushing.

This is now distilled in the Jarman Award. Rupert Everett, actor, director and patron of the Prize, said: “I think that’s what is so inspiring about him, he was a survivor, he wasn’t waiting, ever, to be accepted by the business and given some miraculous black cheque, and I think that is how we should all be looking at this business.” Established in 2008, the Jarman Award acknowledges the diversity and creativity of artists working in film today. It is a celebration of experimentation, imagination and innovation. Creatives who have won the prize include Andrea Luka Zimmerman, Hetain Patel and John Akomfrah.

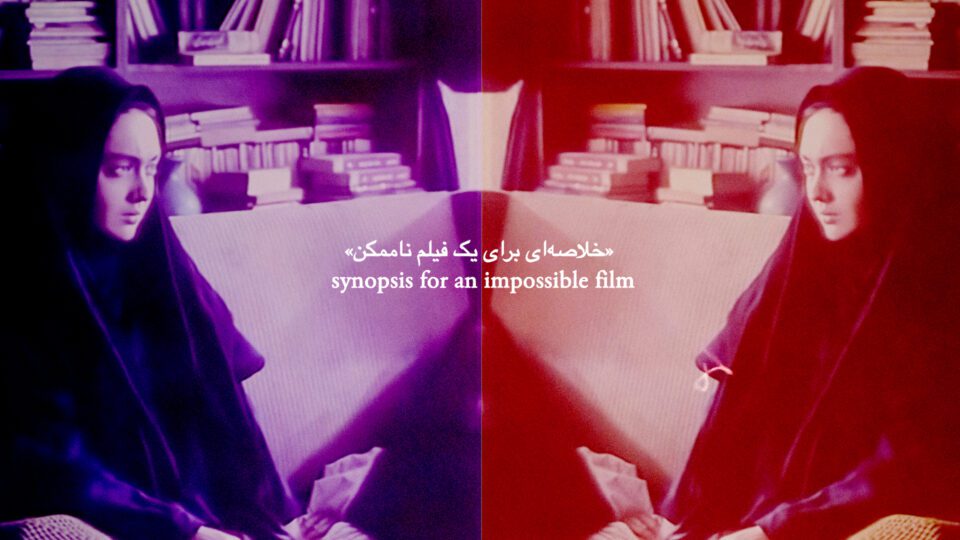

The winner of the 2024 Award is Maryam Tafakory. The Iranian artist works at the intersection of cinema and live performance, considering how objects, words and glances have been used as substitutes for physical contact between men and women in Iranian film history. Matthew Barrington, Cinema Curator, Barbican and member of the jury, said: “Maryam Tafakory’s practice is a compelling exploration of displacement, memory and resistance, interweaving archival fragments, poetry and personal narratives to craft deeply evocative works. Her films navigate historical and personal traumas with remarkable sensitivity, reflecting on the intersections of Iranian cultural identity and individual struggles.”

Tafakory’s work exists in an artistic and political context that began more than half a century ago. Before the 1979 Islamic Revolution, which saw Iran become a Republic and the previous era of modernisation and westernisation reversed, the country’s cinema was booming. Figures like Ebrahim Golestan, Dariush Mehrjui and Sohreb Shahid Saliss drove the industry forward. In the wake of the Revolution, over 180 cinemas were destroyed and many professionals moved overseas. Today, any broadcasting from Iranian soil is controlled by the state and reflects official ideology. Modern filmmakers face severe ramifications for stepping outside of the line. One example is The Seed of the Sacred Fig, due to be released in 2025, which depicts the dangers of complicity with state repression through the lens of an Iranian judge’s family. Director Mohammad Rasoulof was only a few weeks into making it when he received word that a case had been made against him composed of several charges against his previous movies and activism. Facing eight years in prison, he fled the country and now lives in exile.

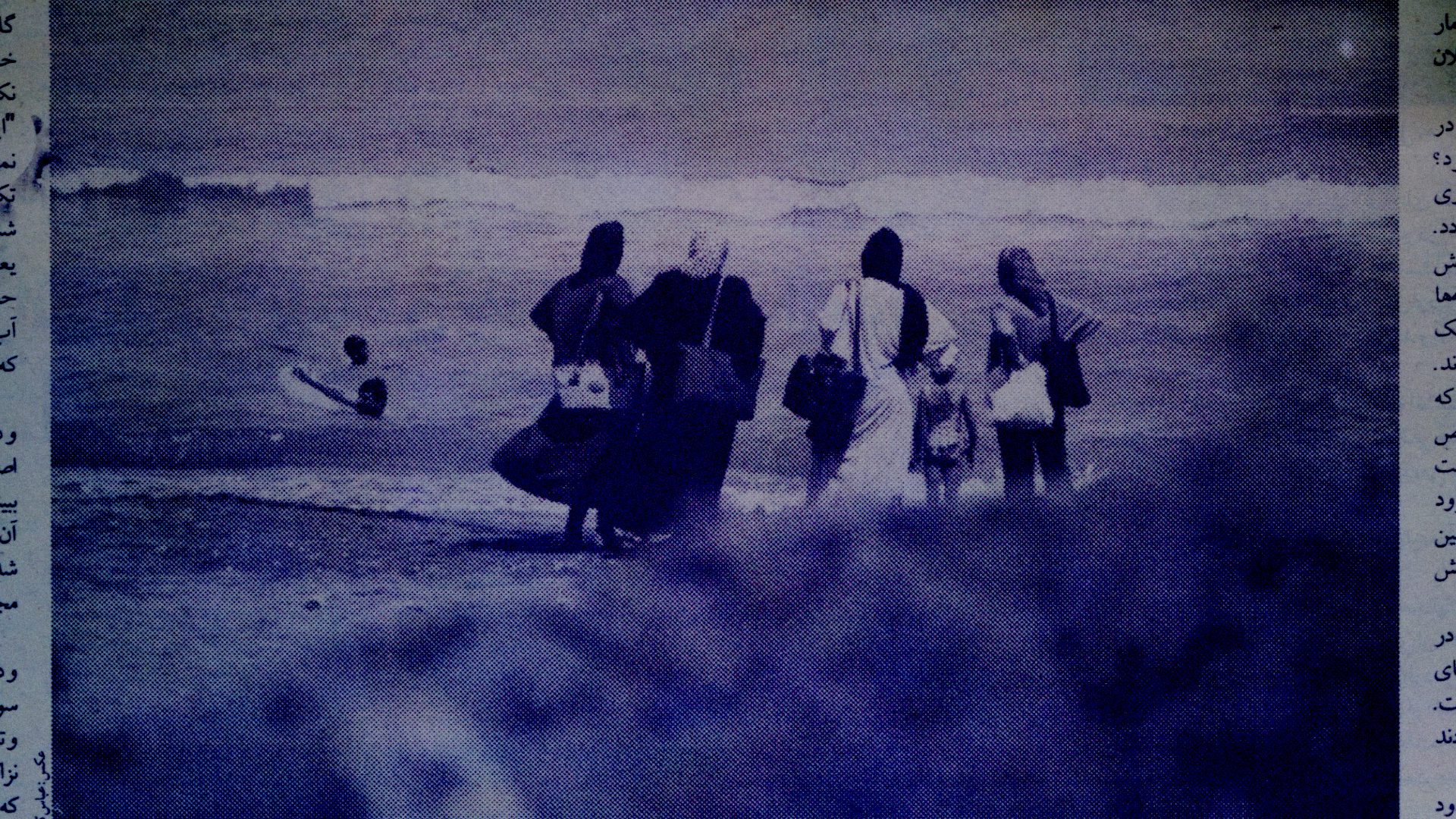

This strong tradition of resistance to oppression continues in Tafakory’s work. Nazarbari (2022) is an abstract, non-linear narrative film about love and desire in Iranian cinema, where depictions of intimacy and touch between woman and men are prohibited. The film focuses primarily on images of women whose bodies have been erased and victimised in post-revolutionary cinema, layering different films with archival text and images. The film uses poetry and silence to explore the discreet forms of communication that operate within, yet circumnavigate the censors. In Mast-del (2023), a forbidden relationship between two women is explored and a love song that would never be approved is narrated through images. It is an attempt to guide us towards the unseen, the everyday.

The artist was a recipient of the Aesthetica Art Prize in 2023 and, in winning the Jarman Award, joins the ranks of Aesthetica Alumni who have been recognised by the jury. Larry Achiampong’s projects employ imagery, aural and visual archives, live performance and sound to intricately explore the complexities of class, cross-cultural dynamics and postdigital identity. Jasmina Cibic won the 14th installment of the Award in 2021. Her stylish, theatrical work tackles important global issues including national identity, nation building, soft power and European relations. British-Nigerian director Jenn Nkiru won the main Aesthetica Art Prize in 2019. It is an impressive list of figures, in which Tafakory rightly belongs, who prove that moving images are an important vehicle for political and social activism around the world.

Films by the six shortlisted artists will be screened at the Whitechapel Gallery across Saturday 30 November and Sunday 1 December: filmlondon.org.uk

Words: Emma Jacob

Image Credits:

Maryam Tafakory, Razeh del (2024), film still. Courtesy the artist.

Maryam Tafakory, CodeNames (performance), (2021–22) Courtesy the artist.

Maryam Tafakory, Razeh del (2024), film still.Courtesy the artist.

Maryam Tafakory, Nazarbazi (2022), film still. Courtesy the artist.