“Mystery feeds my imagination.”

Strange Beauty is the latest book by Erwin Olaf (b. 1959), a Dutch photographer renowned for staging hyperreal worlds – down to their smallest detail. Published to accompany an exhibition of the same name at Kunsthalle Munich, the title brings together photographs from the past 40 years, alongside new series shot over the last year, before and between lockdowns. Here, Olaf speaks to Aesthetica about how recent events have prompted him to reflect on his practice.

A: What was it like to delve back through your archive for this book? Did you discover anything new about your evolution as an artist?

EO: Reading the book, walking through the exhibition, I felt like I was looking at someone else’s work. Both explore, in depth, what moves me, where I came from, where I’m going – making connections in the work that I never thought of myself. For example, I love photographing skin – light, dark, every possible tone – a fascination I’ve had from early on. Also, the way that I was influenced not only by painting but also film. And my interest in the choreography of the body – the way that by moving a shoulder up or down, we can convey our happiness or sadness.

A: Along with older images, the book features new work such as April Fool 2020. Can you tell us a little more about the background to this project, shot in March last year?

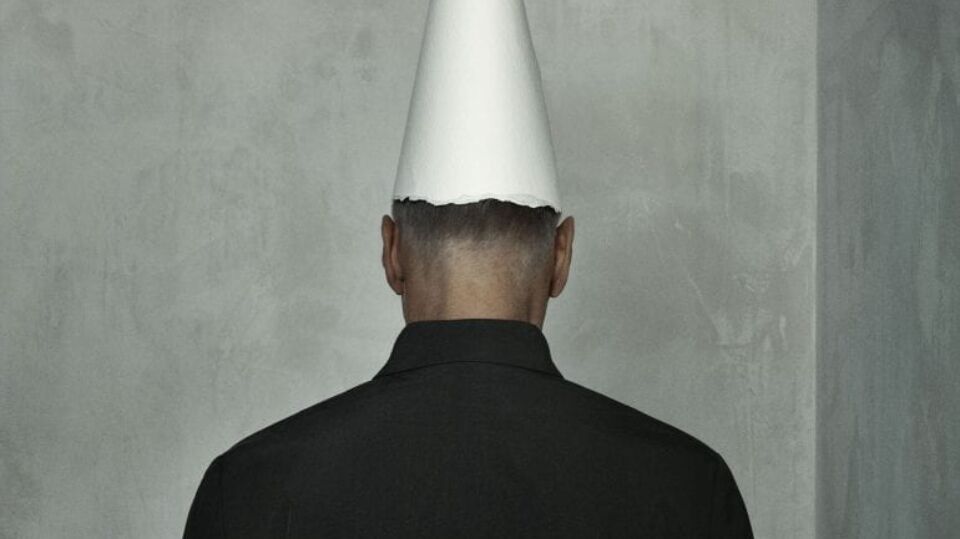

EO: I suffer from a lung disease, and I was in a supermarket when the Covid pandemic started. No-one knew what to do, everyone was panicking, pushing each other. I was paralyzed, I felt like everyone was coming close, that I would get ill and die. To pull myself out of the swamp I had to make this series. I had the idea for the series on Wednesday, shot it on Thursday and Friday and we went into lockdown in the Netherlands on Saturday. The white face is a translation of the unknown emotions I was feeling at that moment. And the white ‘dunce’s hat’ points to how stupid we are as human beings. We shouldn’t have let it come so far. We travel everywhere, we want everything. We are fooling ourselves.

A: The other new series Im Wald (In the Forest), shot outside in the Alps during lockdown in 2020, feels quite different in some ways to your previous work.

EO: When I had this offer of a major exhibition in Kunsthalle Munich, they wanted me to do some new work. The Netherlands is a small country so there’s not so much nature but when you go to the German Alps, you can go for miles and miles with no sign of human architecture. I thought, I have to do something with that. I was inspired by 19th century German Romantic painting, and by Turner. It was about the smallness of a human in comparison to nature. We’re nothing. I shot this in September when Covid cases were lower and the world opened up for a while. Working in black and white, I wanted to show nature’s lack of emotion, its indifference to us.

A: You’re quoted in the book as saying that you are far more influenced by cinema than photography. You say, “I never cry over a photo, but I cry over a movie, or music or literature…” What is it about photography, then, that keeps you taking pictures?

EO: Photography is my talent. It’s a challenge to get as close as you can to the ability of music and movies to engage emotions. I do think it’s possible with photography to go to this deeper layer. I don’t want to dictate the story, I want to give the viewer tools to start to create their own story. I always like to go alone to the cinema because then you don’t need to say it was good or bad as soon as the lights go on. You can think about it while you cycle home afterwards. I want to achieve that in my own work. I get inspired a lot by movies; I tried to be a director but it’s so long and there’s so much money involved. I prefer to shoot short movies and photographs.

A: You talk about giving viewers tools to interpret their own story. Do you have fixed ideas about the narrative within the frame or do you share the viewer’s sense of ambiguity?

EO: It’s like playing with clay. There’s always an initial spark – like the forests in Germany – then I study, look in art books, think, make little doodles of my ideas, but it’s never set in stone. I work like people do in the film industry with stylists, make up, set designers, so you have to translate your idea to a group of people and they come with their input. You hope you’ve done good casting because it’s very important who is playing which role. Then you go to the forest or wherever and that’s when it starts. It can be about the distance between two people, the body language or the smallest camera angle can completely change the meaning of the story. I never know exactly what’s going on. The mystery feeds my imagination.

A: Are there other ways in which the Covid-19 pandemic has impacted your artist practice?

EO: I turned 60 recently, and when you turn 60 everything changes, so this thought process had already started. But, as I’m sure many people feel, after this year of reflection your decisions are firmer. I decided that – except for some assignments that are really inspiring – I only want to make my own art, my own work. I want to take a step back and deepen my practice, to go back to black and white, to go back to the craft. I’m doing more printing by hand. Most of the time photography is very quick. I want to make slow photography.

Strange Beauty is published by Hatje Cantz.

Erwin Olaf: Strange Beauty runs until 26 September at the Kunsthalle Munich.

Words: Rachel Segal Hamilton

Image Credits:

1. April Fool 2020, 11.30am 2020 © Erwin Olaf. Courtesy Galerie Ron Mandos Amsterdam

2. Berlin, Stadtbad Neukölln – 23rd of April, 2012 © Erwin Olaf, Courtesy Galeria Ron Mandos Amsterdam

3. Berlin, Clärchens Ballhaus Mitte – 23rd of April, 2012 © Erwin Olaf, Courtesy Galeria Ron Mandos Amsterdam

4. April Fool 2020 © Erwin Olaf, Courtesy Galeria Ron Mandos Amsterdam