The V&A, London, has collected and exhibited photography since it was founded in the 1850s. On 25 May 2023, the final phase of its Photography Centre will open – the largest galleries in the UK to hold a permanent collection of photographs. Over 600 images across seven galleries – four of which are new additions – will enable visitors to experience the power of photography and its diverse histories in new ways. Archival objects will be displayed alongside dynamic contemporary works from celebrated artists such as Liz Johnson Artur, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Sammy Baloji, Tarrah Krajnak, Vera Lutter and Vasantha Yogananthan, as well as a monumental sculpture by Noémie Goudal. Two major new commissions, supported by the Manitou Fund, will also be unveiled: a series by leading Indian photographer Gauri Gill, and a digital commission by British media artist Jake Elwes, who has explored the use of deepfake technology and Artificial Intelligence (AI) with drag cabaret performance.

The centre’s opening, along with events like Photo London at Somerset House, places the UK as a global leader for innovation in contemporary photographic practice. Ahead of the opening, we speak to the V&A’s Head of Photography, Duncan Forbes, and Senior Curator of Photography, Marta Weiss, about what to expect.

A: The V&A photography collection includes over a million objects, from photos to negatives and technical equipment. How do you navigate a collection with so many items? How do you select images to display? What are you trying to communicate to visitors through your curation?

DF: It is very challenging to work with large photography collections, although this is a situation familiar to many photography curators. The ubiquity of photographic media is both a strength and a weakness: the fluidity makes it a very exciting form to work with – it breaks a lot of rules and can be very creative – but this inevitably causes problems within art institutions, which can be heavily policed by aesthetic tradition. However, the V&A, with its acute focus on materiality and objecthood, is a very good place to think about photography – there are very few barriers to what we can display from the history of the medium. In terms of selection, I pursue two general rules. First, spend as much time physically with the collection as possible. It’s a question of rummaging. This isn’t always easy nowadays and if the pandemic taught us anything, it is that you cannot curate exhibitions off a screen. Second, make space to think and read – good curating is also about having good ideas. Photography is a conceptual form deeply embedded in processes of historical change. These are fascinating and formative but are not always obvious. In terms of reaching out to visitors, we try and give a sense of the vast scope of photography, as well as the aesthetic impact of the material object itself, often in its original form. I believe where possible in fostering a sense of awe and wonder through display and exhibition – curating is about poetry and emotion as well as concepts and historical narrative.

A: The V&A has collected and exhibited photography since it was founded in 1852. The medium has changed dramatically since its origins – with inventions such as Kodak’s Box Brownie in 1900 and the release of the iPhone in 2007 democratising image-making. How does the collection mirror these changes? Can you tell us about an image from the collection that epitomises this for you?

DF: The idea of the democratisation of image-making is tricky and needs to be handled very carefully. I always remember talking to the Scottish broadcaster and writer, Stuart Hood, about his experiences as a communist student in Edinburgh in the 1930s. I had been writing about the worker photography movement for an exhibition at the Reina Sofia Museum and was concerned about the lack of British engagement in the movement. Hood told me he couldn’t recall anyone using a camera in political circles during the 1930s – they were far too expensive. It was a statement that helped reshape my understanding of the documentary movement. It may be that the democratisation of image-making in photography has more to do with the mass consumption-driven expansion of snapshot technologies from the 1960s than some ineluctable process of democratic expansion since the 1840s. So, I don’t think this idea is easily mirrored in the V&A collection. Having said that, it is clear that photography has had an impact on democratic politics, especially during the 20th century. There is a photograph in the Energy display that I find very fascinating in this regard, Sunil Janah’s Street Demonstration in Calcutta from 1942. It shows a street protest against British rule in India and is in fact composed of two negatives – one for the burning vehicle and one for the surrounding street scene. The violence embodied by the conflagration of the vehicle is clearly very significant. It reminds us that photography was also important a process of decolonisation since the 1940s, a subject that is only now being properly explored. Today we need to ask tough questions about the relationship between democracy and image-making. In the age of oligarch-owned social media, deep-fake technologies, corporate capture of editorial regimes, and the demise of social-democratic modes of documentary, the democratisation of image-making may well be going into steep decline. It is not really a question of how many people own camera phones or how many pictures are taken. There are, of course, artists engaged with this problematic. I’ve just written an essay for the Swedish duo, Klara Källström and Thobias Fäldt, who explore these topics in an exhibition opening at the Hasselblad Foundation in Gothenburg at the end of May. They express a profound understanding of some of the historical transitions I mention here.

A: The development of the Photography Centre began in 2017 when the Royal Photographic Society Collection was transferred to the gallery. What can visitors expect?

MW: The arrival of the RPS Collection in 2017 was the impetus for expanding the amount of gallery space for photography at the V&A. The first phase of the Photography Centre, which opened in 2018, more than doubled our footprint and gave us the opportunity to tell new stories by integrating the RPS Collection – which includes 270,000 photographs, along with 8,000 cameras and other equipment – into the V&A’s already vast collection. The second phase completes the Photography Centre with the addition of four more rooms, creating significantly more space for contemporary photography, books and cameras. In fact, at 1000 square metres, it is now the largest suite of galleries in the UK for a permanent photography collection. The rooms themselves are beautifully restored Victorian picture galleries, include a spectacular space for Photography and the Book, where the RPS Library is visibly stored, a walk-in camera obscura and two spacious rooms for the newest photography from around the world. Visitors will encounter photography on the walls, in books, as sculpture, and projected as moving images. They will be able to see one of the best and broadest collections of photography in the world, experience photography and its diverse histories in new ways, and understand photography’s extensive impact on our lives.

A: Energy: Sparks from the Collection will be the first themed exhibition in the completed Photography Centre. What inspired this theme? Can you tell us about some photographs to look out for in the show?

DF: I was working in the USA a few years ago and became very interested in the way that the theme of energy was seeping into the humanities as a topic of enquiry. As a subject it seemed eminently historical as well as speaking to contemporary issues. However, I was surprised that at the time there was so little writing about energy and photography, especially as photography, formed by light, is fundamentally an energetic form. It seemed an interesting idea to explore in relation to the V&A collections. And, of course, it has recently become very topical. The display explores the theme broadly, from the 1830s to the present-day, without being overly didactic. There are many wonderful photographs in the show, but I will pick out four, two by French, and two by German artists. First is Gustav Le Gray’s extraordinary photograph of The Tugboat from 1856, a potent allegorical image about the coming of the steam age. This is followed by Eugene Atget’s Eclipse of 1911, showing the response of a Parisian crowd to a rare solar eclipse in the Place de la Bastille. It is a kind of manifesto for the artist, beloved by the Surrealists, and a photograph I find very moving. Third is Astrid Klein’s mysterious Cerebral Somersault from around 1985 with (for me) its visual echoes of the 1980s nuclear scares. And finally, we are displaying Simone Nieweg’s beautiful, effulgent Cabbage Field of 1990, one of my favourite photographs in the collection and an essay in photosynthesis. It is a photograph that is causing a lot of visitors to stop and stare.

A: Two major commissions will also be unveiled – Gauri Gill’s series and Jack Elwes’ digital work. How did these projects come about?

MW: We are thrilled to be presenting two new commissions supported by the Manitou Fund: a series of photographs called The Village on the Highway by Indian photographer Gauri Gill and the digital project The Zizi Show by British media artist Jake Elwes. They are two very different artists, but collaboration is central to both of their practices, and both use photography – in its most expanded sense – to engage with pressing contemporary issues and to empower the communities they work with.

A: Can you tell us a bit more about the power of photography as a tool for collaboration in The Village on the Highway?

MW: Gill is internationally renowned for her collaborative work with peripheral communities, especially in rural India. For her commission, she documented the makeshift dwellings of farmers occupying major roads leading into New Delhi while they protested new laws that threatened their livelihoods. Barred from entering the capital by police forces, the protesters remained on these sites for over a year from 2020 to 2021. They braved extreme weather conditions and waves of the Covid-19 virus while running community kitchens, or langars, that fed all who came. Eventually, their protests succeeded, and the laws were overturned. Gill meticulously and sensitively recorded the temporary homes, made using repurposed farming equipment, to highlight their ingenious construction. She also made studies of other objects of daily life, like cooking pots and water pumps. Collectively, the series explores design creativity in the face of urgent necessity. Gill’s focus on architecture and design is appropriate for the V&A, a museum of art, design and performance. The formal precision of her work is indicative of the sense of care and attention she takes with the people and places she photographs. Her work demonstrates the power of photography as a tool of communication and collaboration.

A: How does Jake Elwes’ work respond to the future of photography?

MW: The Zizi Show by Jake Elwes is a deep fake drag cabaret that explores the ethical problems that exist in Artificial Intelligence (AI). AI refers to the ability of a computer system to interpret and learn from given data. Although viewed by some as flawlessly neutral, AI applications often show discriminatory behaviour because the datasets they rely on reflect the bias of their human programmers. Elwes observed that computer systems ‘have difficulty recognising trans, queer and other marginalised identities’, which can cause them to visibly break down. They wanted to highlight how this issue in AI contributes to maintaining society’s heteronormative bias. For The Zizi Show, Elwes looked to drag – the ultimate expression of gender non-conformity and constructed identity – to expose and subvert this bias. They consider their work to be both a reclamation of technology that can otherwise be oppressive and exploitative, and a celebration of performance, difference, community and creativity. Shown next door to the V&A’s Theatre & Performance gallery, the subject matter is relevant to other collections at the V&A. The Zizi Show invites contemplation of how digital processes have fundamentally changed the nature of photography. Advances in technology have made photography more accessible and immediate, but they have also given rise to the manipulation and exploitation of images that now infiltrate nearly every aspect of modern life. Elwes’ project delves into the increasingly complex relationship between humans, machines and images.

Photography Centre | V&A South Kensington

Opens 25 May

Words: Cherie Federico | Interviewer: Saffron Ward

Image credits:

1. Hoda Afshar, Untitled #1, from the series Speak the Wind, 2020. Museum no. PH.1222-2022 © Hoda Afshar

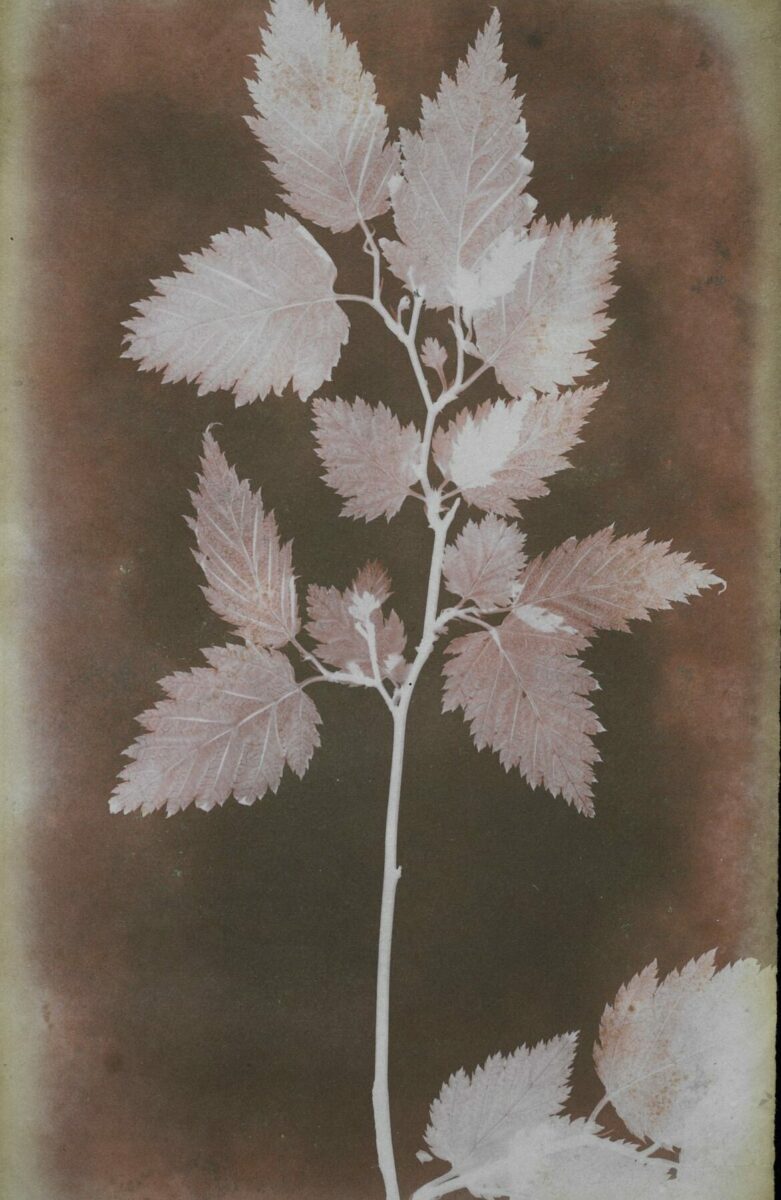

2. William Henry Fox Talbot, Leaves on a stem, c. 1839.

3. Tarrah Krajnak, Self Portrait as Walking Woman with Bag, 1979 Lima, Peru2019 Los Angeles, CA, from the series 1979 Contact Negatives, 2019–22. © Tarrah Krajnak

4. Brian Griffin, Big Bang, 1986. Museum no.E.1064-1988

5. Amirali Ghasemi, from the series Parties, 2005. Museum no. E.355-2010 © Amirali Ghasemi

6. Liz Johnson Artur, Untitled, from the Black Balloon Archive, no date, Museum no. PH.1209-2022 © Liz Johnson Artur

7. CA VA ALLER PRIX ©J.CHOUMALI SANS TITRE 5 HD

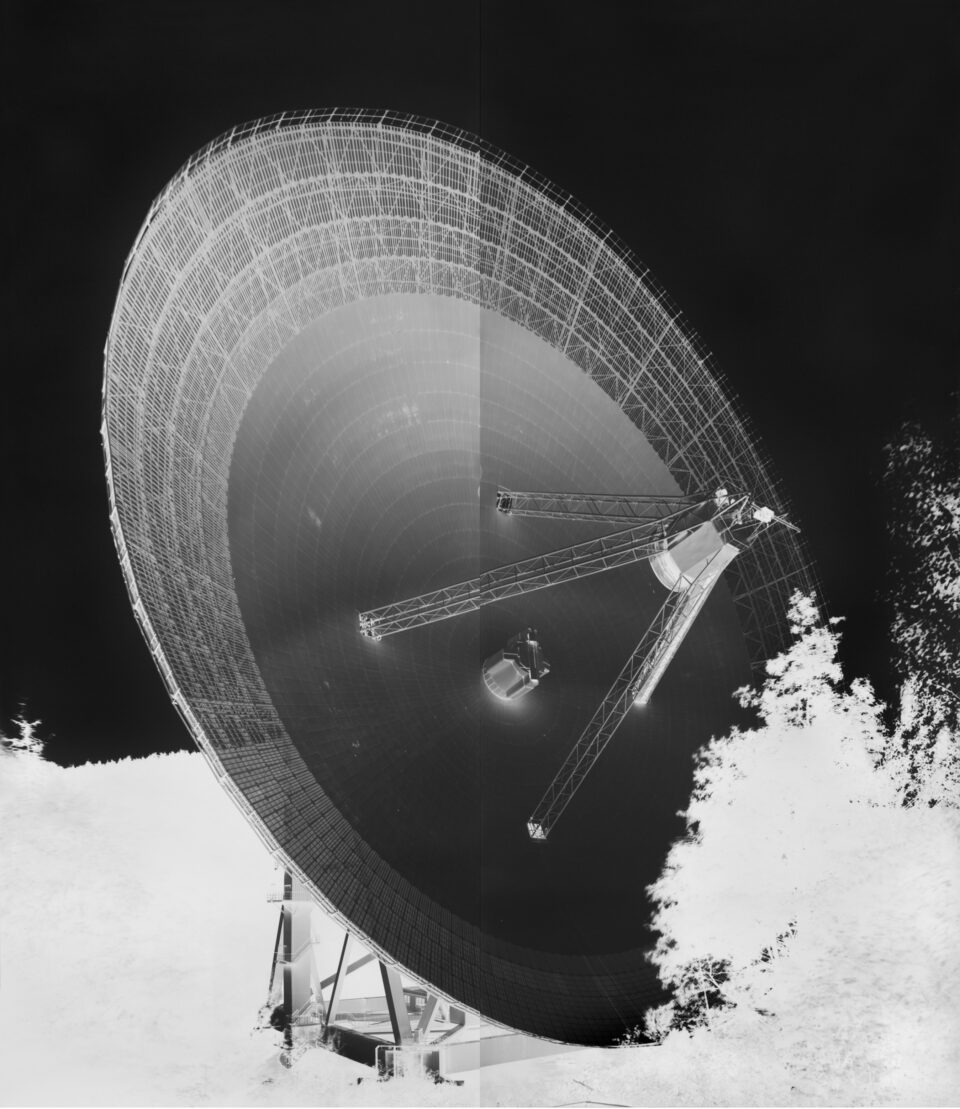

8. Vera Lutter, Radio Telescope, Effelsberg XV September 12, 2013, 2013.. Museum no. PH.430-2021 © Vera Lutter

9. Man Ray, Le Souffle, from the portfolio Électricité, 193. Museum no. E.1654-2001

10. Vasantha Yogananthan, Longing for Love, 2018 from the series A Myth of Two Souls, 2013–20. Museum no. PH.355-2021 © Vasantha Yogananthan