In September 1942, Ruth Asawa (1926-2013) and her family were forcibly moved to the Rohwer Relocation Center – an internment camp in Arkansas that held 8,000 Japanese Americans during WWII. The experience impacted the trajectory of her life. A year later, she was released to train as an art teacher. Engagement with making offered escapism, freedom and possibility. It was a space away from the trauma of racial discrimination. Twenty years later, she established a public arts high school in San Francisco. The institution, now called the Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts, embodies the values of its namesake, representing the power of creativity to change lives. An ongoing exhibition at Modern Art Oxford examines the sculptor’s career between 1945 and 1980, exploring how her dedication to training informed her ethos as a practitioner, mother and advocate.

Ruth Asawa: Citizen of the Universe is the first major solo show of the artist’s work in Europe, with previous presentations at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, and David Zwirner, New York. Drawings, objects, quotes and photographs dig into the connections between her life experiences and holistic practice. One example is a concertinaed structure, developed in 1975 as an initial model for the Origami Fountain in Buchanan Mall, San Francisco. A beige, circular base frames a central open cone, with hundreds of ridges creating depth and movement. The piece utilises the simplest of materials: paper. A flat plane is reworked into a three-dimensional, architectural form through intricate, repetitive folds. The technique builds upon the artist’s lessons with German-born practitioner Josef Albers (1888-1976) at the progressive Black Mountain College, North Carolina, between 1946 and 1949. Asawa was encouraged to be “fully awake to life” and create forms without cutting or sticking. This caused a huge shift in her mindset, shaping her outlook and work. “For Ruth, what she learned, was that art making was more than simply creating objects to put in the world,” explains the show’s Chief Curator Emma Ridgway. “As a process, as a practice for individuals, it can be transformative.”

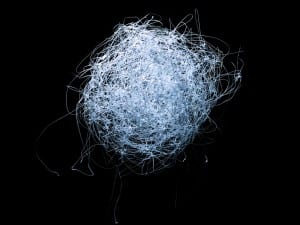

Elsewhere, abstract sculptures emphasise the connections between Asawa’s training and her acclaimed modernist style. Everyday materials are reimagined into natural forms through folding, looping and tying. Elongated, warping shapes appear to merge and blend, hovering like delicate, silk cocoons. Beyond the physical work, lace-like shadows spread across the walls of the gallery. Wintermas, for example, appears to float in mid-air, offering a 360-degree exploration of tree roots. Dark metal overlaps and frays, as if without human intervention. Yet, the piece is also full of control and purpose, with a five-pointed star pattern forming in the middle.

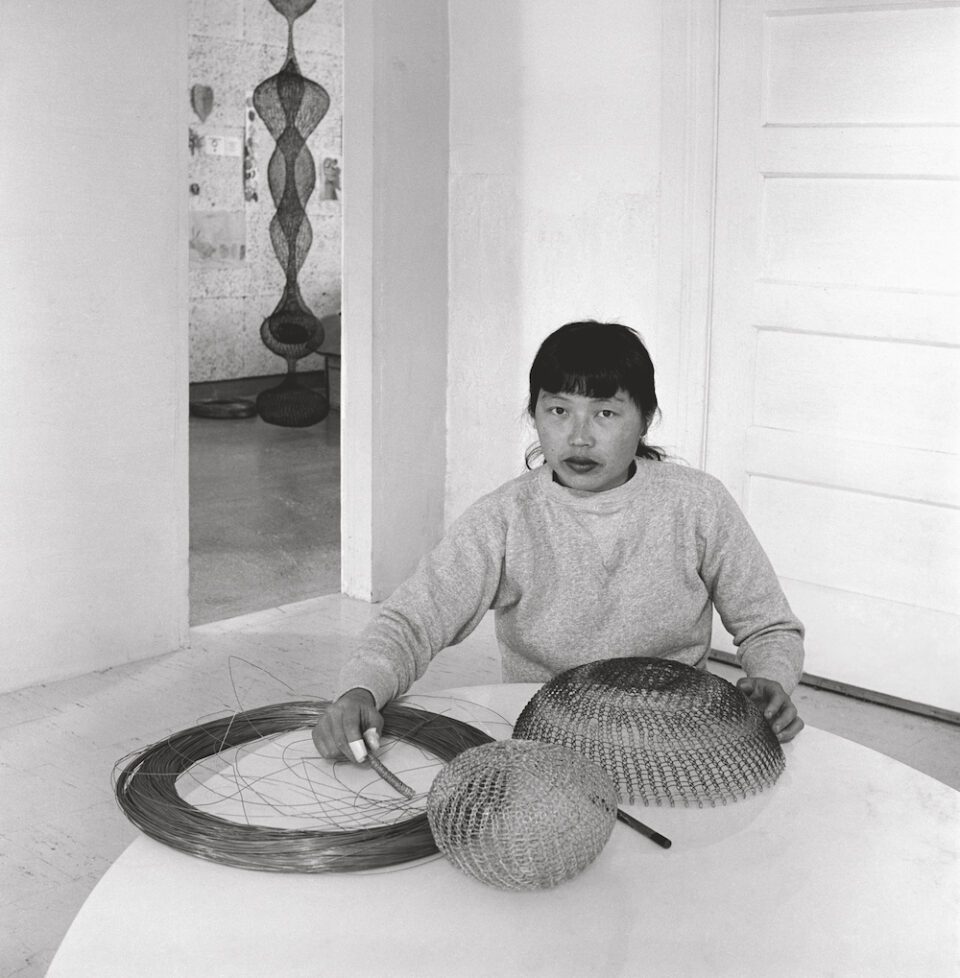

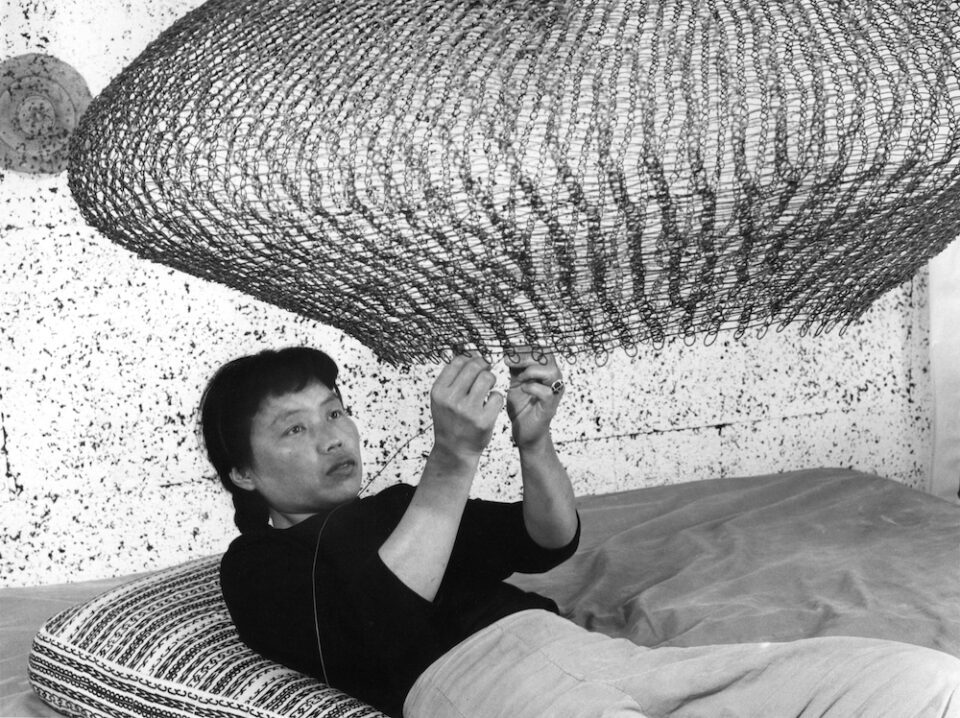

This dedication to self and collective improvement through art engagement is also mirrored in American photographer Imogen Cunningham’s (1883-1976) informal portraits of Asawa, taken in the mid-1950s. In Ruth Asawa 3, the artist is found underneath a looming sculpture, painstakingly twisting a thin length of wire. She is fully consumed by the repetitive process, declining to break focus. The bulbous form above seems to appear from thin air, as the material merges with the spaces in between to create a shape. In another black and white image, Ruth Asawa, Sculptor, Mother, the hanging works frame a group of children, whose figures merge with the shapes. This depiction powerfully encapsulates the sculptor’s ideals, combining her role as a mother and practitioner to highlight the importance of early exposure to colour and design. As she stated: “Art will make people better, more skilled in thinking and improving whatever business one goes into, or whatever occupation. It makes a person broader.”

Ruth Asawa’s barrier-pushing work and words find new relevance today as accessibility to the arts comes under threat in Britain. In 2021, the government approved a 50% funding cut to art and design degrees, redirecting money to STEM subjects. A string of campaigns were set up around the same time, echoing the sculptor’s philosophy of the “integration of creative labour within daily life.” The Contemporary Visual Art Network organised a digital march, with 1,700 people attending and a further 145,000 engaging with the #ArtIsEssential hashtag on social media. Elsewhere, the Public Campaign for the Arts launched a petition for the “proper funding for higher education providers to continue to deliver world-leading arts courses,” gaining over 167,000 signatures. This, plus the popularity of craft and culture during the pandemic, signals a renewed awareness of the personal and collective benefits of creativity – a sentiment that is echoed throughout the exhibition.

Ruth Asawa: Citizen of the Universe runs at Modern Art Oxford until 21 August.

Words: Saffron Ward

Image Credits:

1. Imogen Cunningham, Ruth Asawa in her Dining Room with Tied-Wire Sculpture, 1963. © 2022 Imogen Cunningham Trust. Artwork © 2021 Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc. / ARS, NY and DACS, London. Courtesy David Zwirner.

2. Imogen Cunningham, Ruth Asawa Working on Her Wire Sculpture 3, 1956. Photograph by Imogen Cunningham. © 2022 Imogen Cunningham Trust. Artwork © 2021 Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc. / ARS,NY and DACS, London. Courtesy David Zwirner.

3. Imogen Cunningham, Ruth Asawa 3, 1957. © 2022 Imogen Cunningham Trust. Artwork © 2021 Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc. / ARS, NY and DACS, London. Courtesy David Zwirner.