The African Biennale of Photography, Rencontres de Bamako, was founded in 1994. It was the first international event dedicated to contemporary photography on the continent and remains the most established, acting as a platform to promote creatives from across the diaspora. The Biennale is hosted throughout the capital – from established venues such the National Museum of Mali to the Bamako Railway Station and Ba Aminata Diallo Girls High School – to invite local communities to experience contemporary photographic practices. The 13th edition also celebrates the global exchange of ideas through artists’ talks, workshops and portfolio reviews.

The Biennale was originally scheduled to take place in November 2021. However, due to concerns over Covid-19 and political tensions in Mali, the event was postponed. Andogoly Guindo, Minister of Crafts, Culture, Hotel Industry and Tourism of the Republic of Mali, announced new dates in September 2022. “Despite the difficult context, marked by multiple crises in Mali and all over the world, the Transitional Government wishes to maintain this major cultural event.”

Societal shifts have been documented through photography in Mali since its independence from France in 1960. Photographer Malick Sidibé (1936-2016), who studied art at what is now Bamako’s Institut National Des Arts (formerly École Des Artisans Soudanais), chronicles vibrant city life following the country’s freedom from colonial rule. In these black-and-white scenes, couples perform the Mali Twist, pose half-submerged in the Niger River and play games on its banks. Elsewhere, Seydou Keïta (1921-2001) photographed families in traditional Bogolan clothing across the 1950s and 1960s. These images – featured at Foam Gallery’s Bamako Portraits in 2018 – are more than studio portraits; they preserve history. Guindo’s statement, therefore, reflects the Republic of Mali’s continued commitment to its heritage, highlighting its resilience in the face of political turbulence.

Mali was held under French colonial rule as French Sudan, 1892 to 1960. Following independence, attacks from Tuareg insurgents – attempting to establish an autonomous nation – began in 1962. The Mali Civil War erupted in 1990 after the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MPLA) launched a series of attacks in both Mali and bordering Niger. Peace was coordinated in 1995, but political tensions remained high over the next two decades. In 2012, the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) began another armed campaign, a war which remains ongoing.

In the face of this conflict, the Biennale’s theme, Maa ka Maaya ka ca a yere kono – On Multiplicity, Difference, Becoming, and Heritage, is as a celebration of collective and individual identification, which embraces diversity and the discovery of shared experiences. The event delves into “composite, layered and fragmented identities,” presenting the work of over 75 African artists, from countries including Egypt, Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa and Zambi, amongst others. Its curation is a similarly collaborative process: Artistic Director Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung is joined by Co-Curators Akinbode Akinbiyi; MACAAL Artistic Director Meriem Berrada; Zeitz MOCAA Assistant Curator Tandazani Dhlakama; as well as artist and curator Liz Ikiriko. These creatives go beyond the self to consider “complex and non-linear understandings of space and time,” reflecting on perceptions of individuality. Ndikung also views regaining “multiplicity, fragmentations and points of intersections of different ways of being” as a facet of decolonisation. Exhibitions across the world counter existing colonial power structures by giving space to underrepresented voices. In 2022, Pace Gallery, London, launched Living With Ghosts, a group exhibition curated by writer KJ Abudu, speaking to the unresolved traumas from Africa’s colonial past that continue to pervade present-day society. Africa Fashion at V&A, London, open until April 2023, provides African creatives with a platform for discussion and takes a wider look at the African Cultural Renaissance, a period of immense creativity following the “African independence and liberation years” from the 1950s to the 1990s.

However, Mark Sealy, Director of Autograph, London, criticises the French influence on Rencontres de Bamako in his book Decolonising the Camera (2019), which interrogates historical racial influences on photography and how to dismantle colonial legacies. Whilst Institut Français still sup-ports the event, the Biennale maintains that it moves away from “forces that have held a huge part of the world under bondage for too long.” Its focus is on artists from across Africa and its widespread diaspora. By engaging with notions of selfhood and unity, this edition acts not only as an exploration but a reclamation of complex, expanding identities.

Therefore, the festival features retrospectives for established artists, including Joy Gregory (b. 1959), Jo Ractliffe (b. 1961) and Samuel Fosso (b. 1962), alongside over 70 contemporary imagemakers. This includes self-taught Moroccan photojournalist Seif Kousmate (b. 1988), whose photography engages with migration and youth in Africa, and Muhammad Salah’s (b. 1993) multidisciplinary work, which questions notions of freedom, identity and sexuality. David Uzochukwu (b. 1998), born in Austria to Austrian mother and Nigerian father, residing in Berlin, is amongst the youngest artists. His photographic observations, which use speculative fiction as a vehicle to examine race and migration, are well documented across the commercial and the fine art world.

Uzochukwu shot a Nike campaign with FKA Twigs aged 17, and he has collaborated with Pharrell Williams, Dior, Dutch fashion designer Iris van Herpen and Swedish electronic band Little Dragon. His series Giving Way (2016), based on the work of Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe, featured in the Lagos Photo Festival in 2016, whilst Mare Monstrum/ Drown in My Magic (2016-ongoing) exhibited in Unseen Amsterdam three years later, alongside contributions to Photo Vogue Festival 2021 and Paris Photo 2022. Uzochokwu was featured in The New Black Vanguard, curated by Antwaun Sargent to celebrate “this generation’s Black imagemakers, who are bringing fresh perspectives to photography.” The landmark exhibition was presented at Rencontres d’Arles in 2021 and is at London’s Saatchi Gallery until January 2023.

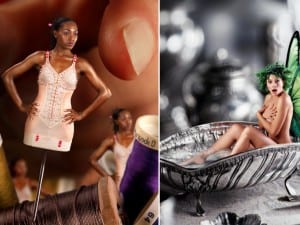

His speculative works have been documented in In the Black Fantastic (2022), a publication and exhibition shown in Hayward Gallery, London, in summer 2022. Black artists created experimental work across different artistic mediums to imagine future possibilities for Black communities and life on Earth. Through his works Wildfire (2015), Uprising (2019) and Shoulder (2019) denoted in the volume, curator Ekow Eshun (b. 1968) states: “Uzochukwu reclaims the narrative of fantasy by embracing the alien otherness projected onto Black bodies in a way that could be read as pure empowerment.” When science fiction is still dismissed as pop culture entertainment, Uzochukwu appreciated that In the Black Fantastic took “speculation (and its limitations) seriously as a form of expression and as groundwork for conversation.”

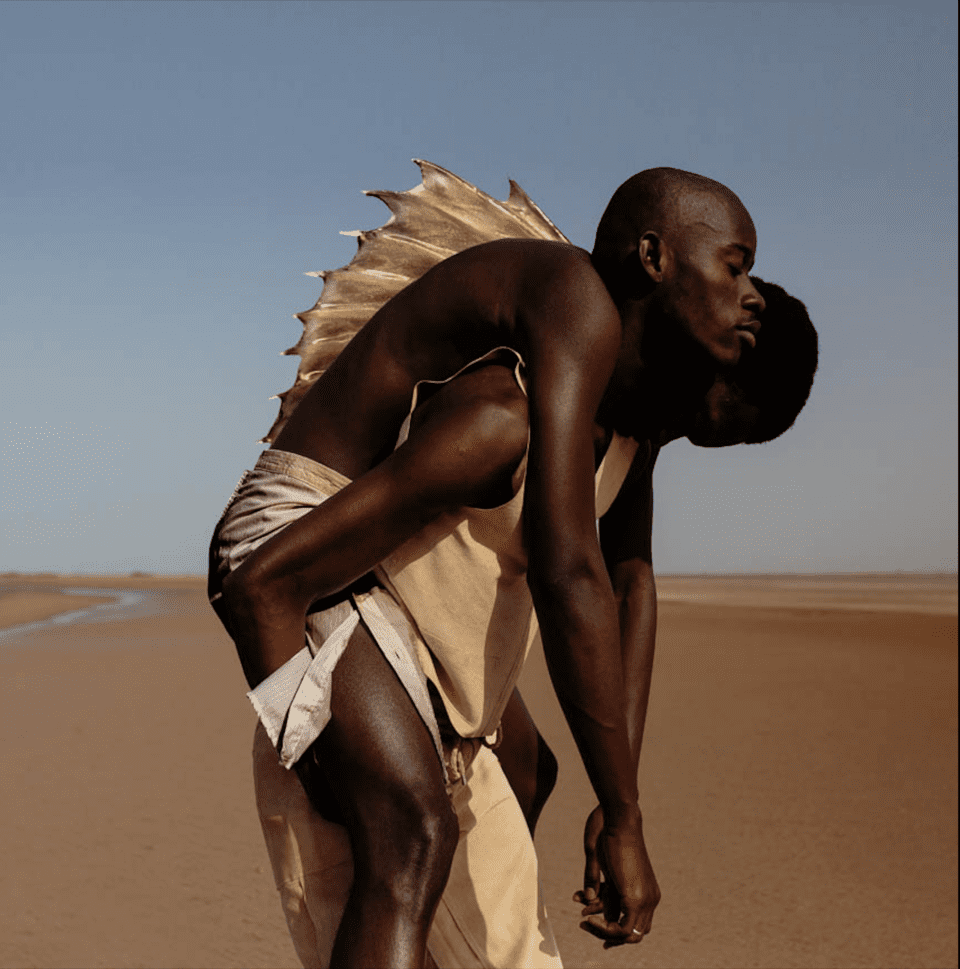

This discussion remains in his ongoing series, Mare Monstrum/Drown in My Magic. For example, Styx (2020), depicts Black mermen shot on the coast of Senegal – a location where migrants gather to cross to Europe. This project also references the Middle Passage, the capture and enslavement of African people across the Atlantic. “The visuals were political,” he says, referencing the influx of photographs taken in 2016, when people arriving at European shores were sensationalised by the press. “They’re fighting for their lives, or they have lost their lives, and the images were dehumanising. I was interested in vulnerability, intimacy and connection.”

These initial works explored migration to Europe. However, Uzochukwu began to experiment with images surrounding the African diaspora and the sea, with water’s recurring presence across the series a reclamation of this relationship. Figures intertwine on beaches, whilst merfolk and centaurs are embraced by waves. These images of safety and freedom offer new perspectives on belonging within the environment.

Ecological concerns are also evident in Mare Monstrum/ Drown in My Magic, envisaging a world where humans are unified with nature. “I’m interested in the separations that we draw up between the human, the animal and our environment,” he says. “How they’re distinctly shaped, formed and separated from each other.” Uzochukwu bridges the gaps to re-evaluate these existing relationships, proposing theoretical futures that foreground symbiosis with nature.

The unification he poses questions our existing and continued use of fossil fuels. “I have included oil as a particular example of our power relationship with the environment.” Similarly, in Wildfire (2015) – included in the 2021 Prix Pictet Global Award in Photography and Sustainability – a young woman poses with hair made of smoke, recalling the ashes of natural landscapes destroyed in the search for energy.

Whilst he remains wary of the connotations of entangling nature with Blackness, Uzochukwu views his work’s environ- mental aspects in terms of decolonisation. “Europe only knows how to sustain itself through suppression and exploitation,” he says. Colonialism entrenched the view that mate- rials, crops, enslaved people and whole countries could be viewed as resources, and it is western capitalism taking Earth to the brink of environmental collapse. The portraits offer new perspectives on these relationships, fostering conversations on responsibility and resilience in the climate crisis.

Uzochukwu’s work, like the life cycles of his fantastical creatures, exists in “phases.” His photography is in a process of renewal, as he completes his BA in Philosophy and Cultural Studies at Humboldt University of Berlin. “I’ve been delving more into films,” he says, when asked what is next for his practice. “I’m looking at how to build narrative within that.” The resulting docufiction Civil Dusk (2022), which debuted at CPH:DOX 2022, is a short following an Igbo tradition, where all sons must build a house in their Nigerian family village.

Rencontres de Bamako exemplifies continuous evolutions of practice and identity. Depicting diverse facets of humanity provides more opportunities for expression, compassion and, ultimately, global change. Ndikung states: “If the world is to survive the dire moments in which we all find ourselves, then we must embrace passage from unity to multiplicity.”

Words Diane Smyth

Rencontres de Bamako | African Biennale of Photography, Bamako Until 8 February

Image Credits:

1. David Uzochukwu, Wildfire (2015)

2. David Uzochukwu, Buoyant (2019). From the series Mare Monstrum/Drown In My Magic

3. David Uzochukwu, Shudder (2020). From the series Mare Monstrum/Drown In My Magic.

4. David Uzochukwu, I Will Learn To Love The Skies I am Under (2015).

5. David Uzochukwu, Shoulder (detail) (2019). From the series Mare Monstrum/Drown In My Magic.