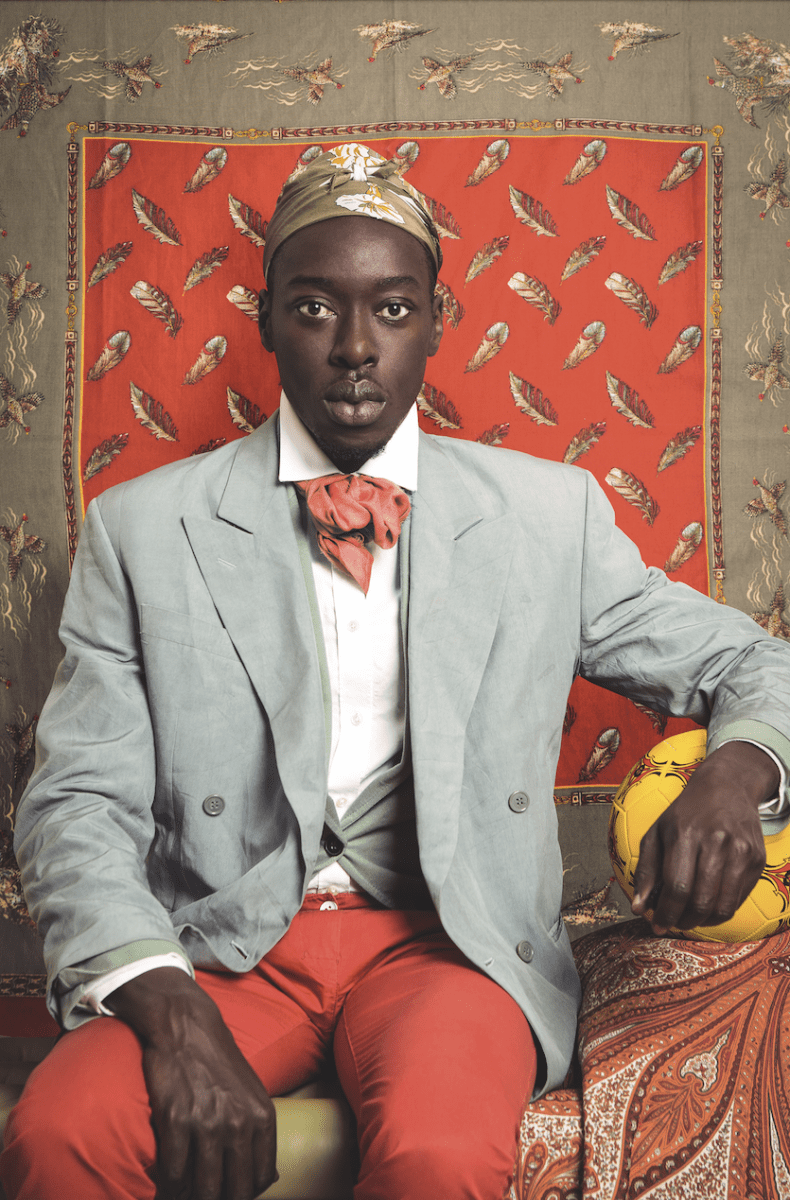

In a 2015 photo-study, Omar Victor Diop (b. 1980) places himself in the guise of Muslim scholar Omar Ibn Saïd, who was born in Senegal in 1770 and sold into slavery in North America in 1807. Saïd produced a remarkable memoir which stands as one of few surviving slave narratives, and the only known text of its kind in 1850. His portrait, shown here, is updated with drapery reminiscent of the European Rococo era.

Diop was born in Senegal’s capital Dakar, where he still works. His portrait of Saïd is from a series exploring African interactions with, and exploitation by, white European culture. In other pieces he assumes the role of Gustav (Albert) Badin (c. 1747-1822), enslaved foster child and servant to Queen Louisa Ulrika of Sweden; and Dom Nicolau (c. 1830-1860), ruler of the historic kingdom of Kongo and an early protestor against colonialism. These subjects are shown posing with bright yellow footballs, goalkeepers’ gloves and referees’ cards, as well as various other footballers’ props. They sug- gest the simultaneous veneration of, and hostility towards, African sportsmen amongst white fans, a present-day analogy for Badin, Saïd and other early movements to the west.

Diop is a hugely successful figure in the worlds of fashion and advertising, and the most recent of a string of pioneering West African studio photographers who have captured the culture of their nations either through, or alongside, a commercial practice. He is also one of over 300 artists included in Phaidon’s encyclopaedic new volume African Artists: From 1882 to Now, which spans a veritable galaxy of styles and eras: from the expressive realist paintings of Nigerian Aina Onabolu (1882-1963) – seen as a forefather of modern African art – to contemporary installation works by artists such as Magdalene A.N. Odundo (b. 1950). In Odunduo’s Transition II (2014), 1,000 glass pieces are suspended from the ceiling, inspired by the forms and contortions of the human body as both a collective and an individual vessel.

Each African nation differs hugely, responding to what historian Ali Mazrui, (1933-2014) calls Africa’s “triple heritage”: indigenous, Arab / Islamic and European Christian. The sheer size and demographic diversity of the continent and its geographies has sparked a wealth of artistic movements over the last 150 years, and this is clear in African Artists: From 1882 to Now. However, certain experiences, like the trauma of imperial subjugation, are held in common for many artists. Film Noir Cadre Doré 2 (2017), made by Togo-born Clay Apenouvon (b. 1970), for example, shows a black viscous substance spilling out of a luxurious gilded frame onto the gallery floor. The work acts as a grim indictment of imperial resource plunder and the European culture that profited.

In a similar fashion, Rwandan sculptor Valerie Piraino (b. 1981) produced Niger Delta Blues III (2016). The piece comprises five marulas (fruits indigenous to South Africa) cast in black epoxy clay, hanging from a net that both secures and controls. These fruits, and others such as papayas, are recurrent in Piraino’s work, with the papaya’s presence in sub- Saharan Africa itself an outcome of colonial exchange.

Beyond certain shared histories, further connections can be found in both aesthetics and technique. Omar Victor Diop’s recent experiments in studio and fashion portraiture, for example, can be traced back to a number of influential mid-to-late 20th century photographers based in Mali. Seydou Keïta (1921-2001), a native of capital city Bamako, established his famous home studio in 1948, photographing up to 30,000 of the city’s inhabitants during the period of economic and demographic expansion following WWII. Malick Sidibé (1935-2016), of a younger generation than Keïta, expanded on Mali’s rich legacy of studio photography. Sidibé was a cattle herder’s son inspired by the cultural blossoming that followed independence from France in 1960. Before turning to formal shoots in the 1970s, he produced joyous images of Bamako youth and nightlife. The infamous Nuit de Noël (Happy-Club) (1963) shows two young dancers with their heads inclined towards each other in intimate reverie, feet poised in time with a faraway beat.

Similarly inspired by the studio portraiture of Sidibé and Keïta is Atong Atem (b. 1991), who’s also listed in Phaidon’s title. Atem’s works, such as Self Portrait on Mercury (2017), are an act of resistance, questioning why we are photographed, and for whom. Atem was born in Ethiopia to south Sudanese parents and escaped the second Sudanese Civil War of 1983-2005, before arriving in Australia at age six. Her self- portraits, which often involve luminous face paint along with surreal and futuristic props, play on her sense of alienation in a white-dominated country, subverting the Eurocentric gaze which would see her, first and foremost, as “other.”

The camera is also a gateway to abstracted versions of the self, as seen through a number of featured artists. Eritrean Dawit L. Petros (b. 1972) grew up between Ethiopia and Kenya, and now lives between Chicago and Montreal. His staged photographs are centrally concerned with cross- cultural exchange and migration. Models are often placed in eccentric poses on vast or sublime landscapes, signifying both the insignificance of human life and our continued pull towards the horizon. Single Cube Formation, No. 4, Nazareth, Ethiopia (2011) is part of a series which sees subjects spread across continents, each scene featuring an empty cardboard box which faces the viewer like a window into the void. The gesture references destitution, but also retains an element of anonymity and privacy, whilst alluding to the concepts of minimalism and the black block as an avant-garde motif.

Furthermore, the case of Zina Saro-Wiwa (b. 1976) is particularly interesting. Born in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, Saro- Wiwa works as an artist and activist, documenting sustainable, local food cultures. The Table Manners film series (2014- 2016) uses vibrant colour palettes to show people using their hands to eat meals made from local produce, positioning food as “an experiential reliquary of marginalised tradition.” The series highlights the performative practices of food consumption, and the role that dining plays in defining communities. It also references the philosophies of 19th century French gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, who, in the 1825 title The Physiology of Taste, wrote: “Tell me what you eat and I shall tell you what you are.”

Innovation is, therefore, linked to cross-cultural exchange, and it’s crucial to discuss the emergence of contemporary African art in relation to the experience of modernity. For Chika Okeke-Agulu (b. 1966), Professor of African and African Diaspora Art at Princeton University, one point of interest is “the rich traditions of modern art that emerged in the work of African artists at the turn of the 20th century, just as their counterparts in Europe – thanks largely to artistic resources put at their disposal by colonialism – were developing their own modern art.” Cairo was one hub of invention, with sculptor Mahmoud Mukhtar (1891-1934) inverting European “Egyptomania” – a notable influence on Beaux-Arts and Art Deco style – with crisp, hieratic statuary referencing the country’s ancient monuments.

Where a likeness of the sphinx in western public art would have signified exotic curiosity, in early 20th century Egypt, civic works such as Nahdat Misr (Egypt’s Awakening / Egypt’s Renaissance, 1928) expressed anticolonial ambition and the reclamation of a shared past. By the time European empires were crumbling across the 1950s and 1960s, a number of regional traditions across Africa had seized cultural sovereignty. In this context, “new- fangled ideas about national culture” melded with the “rec- lamation of indigenous and Islamic art traditions,” resulting in what Okeke-Agulu defines as “a postcolonial brand of modern art.” Broadly, this meant an intensive formal experimentation with indigenous forms and design, and the association of the resulting modernist painting and sculpture with cultural authenticity and sociopolitical self-determination.

For Okeke-Agulu, “contemporary art” in Africa emerged “in the wake of a reassessment by artists and citizens of Africa’s realities after the euphoric period of political independence.” Until the 1970s, African art, in spite of its variety, broadly “participated in the collective imagining of a new culture and society.” Wider concepts and movements such as Pan- Africanism, Négritude, and even Pan-Arabism provided some basis for combined and collective endeavour. By contrast, “contemporary art tend[s] to be critical or sceptical of such concerns, largely because of widespread disappointments with – and failures of – post-independence nation building.”

Having said this, Okeke-Agulu draws attention to various infrastructural and economic models that have created the conditions for large-scale creativity across the continent. From the rise of international residency networks from the 1970s to better-resourced institutions since the 1990s and, more recently, the advent of major events such as ART X Lagos in Nigeria, Cape Town Art Fair and 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair, African art is receiving global acclaim.

Ghana’s debut pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale, de- signed by architect David Adjaye, speaks of a sea-change, as do the major retrospectives offered to the likes of Zanele Muholi (b. 1972) and Julie Mehretu (b. 1970) by the Tate and Whitney respectively. Muholi’s run at Tate Modern was so successful, and so considerably popular, that a follow-up exhibition is being planned in the same venue for 2023.

Even with these groundbreaking practitioners making their way onto the walls of global institutions, being seen by thousands and provoking vital conversations about inclusive programming, it’s crucial that western audiences reflect on their terms of engagement. Okeke-Agulu expands: “One of the most enduring yet paradoxical statements ever made about Africa, and one which has shaped perceptions of the continent, was popularised in the 16th century but credited to the Roman writer Pliny: ‘Always something new out of Africa.’

Okeke-Agulu continues: “This newness wasn’t meant to signal that Europeans of the ancient world – or of the age of exploration – looked to Africa as a source of progressive developments; rather Africa was the land of exotic animals and people, an unending source of surprising curiosities, remnants of evolutionary oddities. Even to this day, and despite slow but halting recognition of African artists’ participation in the making of modern art, the ‘out of Africa’ attitude endures.”

Words: Greg Thomas

African Artists: From 1882 to Now is published by Phaidon

Image Credits: 1. Omar Victor Diop, Omar Ibn Saïd (2015). © Omar Victor Diop.Courtesy Galerie MAGNIN-A, Paris. From the series Diaspora. Pigment inkjet printing on Harman by Hahnemühle paper.

2. Zina Saro-Wiwa, Precious Eats Boli & Fish with Oil Bean, from Table Manners, Season 2 (2019). Digital video, 5 mins 37 secs. Picture credit: Courtesy the artist and Tiwani Contemporary.

3. Atong Atem, Self Portrait on Mercury, (2017). From the series Self Portrait As. Digital colour photograph, 90 × 60 cm, (353/8×235/8in),editionof10+2 AP, private collections. Picture credit: Courtesy the artist and Mars Gallery.

4.015). © Omar Victor Diop.Courtesy Galerie MAGNIN-A, Paris. From the series Diaspora. Pigment inkjet printing on Harman by Hahnemühle paper.

5. Zina Saro-Wiwa, Dorcas Eats Roasted Snails and Drinks Maltina, from Table Manners, season 2, 2019. Digital video, 6 mins 47 secs. Picture credit: Courtesy the artist and Tiwani Contemporary.