It sounds like a storyline from a soap opera. Diana Markosian (b. 1989) was seven years old when she arrived in Santa Barbara, California, having moved from Moscow with her mother and older brother. They were there to visit a family friend, Eli, but the stay ended up becoming permanent when Svetlana, her mother, married Eli. It was only 20 years later – when the artist and her brother reconnected with their father, visiting him in Armenia for the first time since they’d left Russia – that Markosian discovered the truth about their migration. In fact, her mother had never met Eli before stepping off the plane on that day. The two had only corresponded through letters, having been introduced to one another by a matchmaking agency that helped women in former Soviet countries find American men to marry – their ticket to a brand new life.

In a way, it is a storyline from a soap opera. Markosian’s parents, both well-educated Armenians – an economist and an engineer – had moved to Moscow to complete their PhD studies in 1991. Here, they found themselves destitute in economic turmoil following the end of the Soviet Union. They had separated before their daughter was born. Svetlana, disillusioned with a new political reality, was an avid viewer of the American soap opera Santa Barbara. The 1980s series was hugely popular in Russia at the time – amongst the first western shows to be aired after the collapse of communism. It became one of the country’s longest-running programmes, screening from 1992 to 2002. The glamorous, sun-drenched lives of its attractive, wealthy characters – in particular the on-off romance between “supercouple” Eden Capwell and Cruz Castillo – inspired a heady fantasy in Svetlana.

Santa Barbara is also the name of Diana Markosian’s most recent body of work, made in 2019, a 14-minute short film and accompanying set of cinematic still images, currently on show at the International Center of Photography (ICP), New York, and concurrently at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. The project follows two other highly personalised series, including Inventing My Father (2013-2014) and Mornings (With You) (2016), in which the artist explored the strange experience of re-establishing familial relationships after decades without contact. “It’s an attempt to understand [my mother],” she says of Santa Barbara. “There’s the initial shock, disappointment and anger, but I wanted to go beyond those feelings and really see my parents as people.” The title is more than a passing reference to her mother’s favourite TV show, it’s “the thread that held it all together,” says Markosian, who collaborated with one of the soap’s scriptwriters to reimagine Svetlana’s emotional and geographical journey.

“Because this felt so dramatic and painful, I needed to in- troduce an element of playfulness,” she says. In the exhibi- tion, Svetlana’s journey is presented through an immersive installation that takes visitors into a small, intimate room – decked out to resemble a domestic interior in 1990s Moscow (complete with a retro telephone and overflowing ashtrays). A grand entrance gives way to a larger space – representing the idealised American Dream. The short film is projected, life-size, on a wall, and all around the space are still images restaging snapshot-like memories of the family’s first year there – the wedding, honeymoon and Christmas Day, as well as more lyrical close-up portraits that hint at Svetlana’s inner struggles.

Finally, visitors come to a heavy curtain, which can be pulled aside to reveal portraits of the actors playing the “characters”, along with video footage of their auditions and a print-out of the film’s script, which has been annotated. There are differences between Markosian’s art and the original soap opera – not least the way that the former deliberately displays its own artifice. And yet it’s interesting that both depend on lens-based media. Is there something inherent in all film and photography, whether it’s fine art portraiture or an episode of EastEnders, that produces a uniquely strong sense of empathy or engagement? In the 1935 essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, German philosopher Walter Benjamin said that: “The audience’s identification with the actor is really an identification with the camera.” As such, it’s the editorial choices that make screen- based media so powerful, perhaps more so than real life.

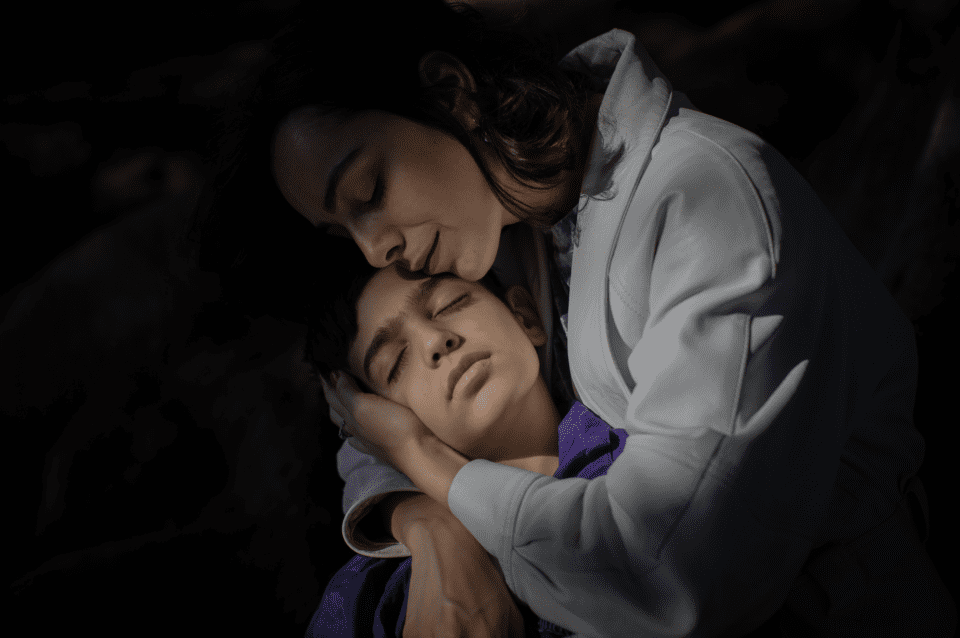

The director or photographer manipulates our feelings, pulling us close or pushing us away from the action. We become lost in an experience that mimics embodiment. This can be seen in various still portraits of Svetlana, for example. She is usually shown up close, and almost always looking anxiously beyond the frame, as though searching for something. Her body is listless, slumped back on a car seat or collapsing into Eli’s embrace, but her face glows, lit by the bright Californian sun or the flickering of a TV screen. In a portrait with her son, the mood shifts, however. Here, she is in charge, her body framing his, with a tender smile. Her eyes are closed in blissful devotion – like a modern-day Madonna.

Diana Markosian had no agency in the decisions that led to her move to the USA as a seven-year-old child, but as an artist, she reclaims ownership over the narrative through the lens. However, working creatively with documentary has its own ethical issues. There’s a risk that the people who are being semi-fictionalised will feel betrayed or misrepresented. Markosian’s family were “fully involved” in the process. “My mom crossed out my lines and wrote her version of it. I gave it to my father; he crossed out more lines,” she says. “My greatest joy was seeing my family come together to remem- ber something we all disagreed on.” The contrast between how different members of her family recalled the same events was striking. Beyond certain, indisputable facts that they could agree upon as objective truth – the date they left, say, or the flight they took – each brought their own emotional reality, a kind of subjective filter. Although Markosian took all this into account, ultimately, she was presenting her singular take on things. “There are parts of it [my mother] really didn’t appreciate,” she admits, “but she accepts it.”

“I lean towards the personal narrative because it’s the one that I feel the most authority over. I don’t have that sense of wanderlust anymore. I’m comfortable staying where I am and deepening my sense of place and self.” Throughout making this work she occupied a dualistic role, “dissecting as an artist and mourning as a daughter.” Much of art today is, like this, a form of self-portraiture, from Tracey Emin’s My Bed (1998) to LaToya Ruby Frazier’s photography book The Notion of Family (2014). These “personal narratives” were once taken less seriously, precisely because they give marginalised groups the power to voice their own perspectives.

However, contemporary culture, moving with the currents of identity politics, is becoming more attuned to asking: to whom do stories belong? And who has the right to tell them? The history of photography, in particular, is littered with instances of ethnographic exploitation. Until very recently, many photographers would routinely travel the world, capturing images of communities, often without their consent, the results intended for consumption by a western audience. In the past decade there’s been a pushback against this, through grassroots organisations such as the The Everyday Projects, which champions “localised storytelling,” launching in 2012 with Everyday Africa and now including Everyday Eastern Europe and Everyday India. There’s also Diversify Photo: “a community of BIPOC and non-western photographers, editors and visual producers working to break with the predominantly colonial and patriarchal eye through which the mass media has recorded the images of our time.”

For some artists, Markosian included, this work also functions as a form of therapy. “There’s a lot of shame that comes with the way [my mother] came here,” she says. “This project was a way of coming to terms with that. That is what I hunger for in art – growth.” In a particularly fascinating, memorable sequence, Svetlana sits across the table from the actor playing her, and is quizzed on her motives as a younger woman. The project’s continuous interplay between reality and re- construction – its conscious dismantling of the “fourth wall” – reminds us that this narrative, and by extension all narra- tives through which we understand our lives, are unstable. We subject them to mental rescripting as we contemplate things from different vantage points over time. Markosian reminds us that we can, and often do, choose how we understand our lives. Now, rather than resenting her mother, she has come to respect her authorship over both their destinies. “She paid the ultimate sacrifice as a woman to give me a different life.”

Markosian insists that the intended audience for the work was her mother. And yet, here it is, on display at ICP, and discussed in an international art magazine. If it had only ever been her and her family who saw the film, would it still be art? Isn’t a work, after all, only to be considered as art because it is received, as such, by a wider public? This was the point made by Marcel Duchamp back in 1917 with the readymade sculpture, Fountain. Take away its context and we’re left with a urinal. Every family has their stories and, even when they have a huge plot twist like this one, it takes something more to make them meaningful for a viewer not directly involved. They need to invoke an affinity that transcends the specifics of the situation. “I think there’s a bit of narcissism with personal work and I get scared of going down that route,” says Markosian. “You hope that your art touches someone beyond you, but it’s not something you can control.”

Artists, whether or not they deal in the currency of personal narratives, are compelled at a certain point to set their work free. Once unleashed into the world, projects take on a momentum of their own – although this is invariably called into question when the creator does something that casts an ethical shadow over the piece. The cultural reckoning that came with the #MeToo movement, for example, made popular films uncomfortable viewing as a consequence of their association with certain writers, directors or actors. Soap operas, possibly more than any other genre, seem to belong to their audiences rather than the creators. The writers of Coronation Street or EastEnders may not have predicted that Bet Lynch or Pat Butcher would become gay icons. Similarly, the writers of Santa Barbara probably wouldn’t have anticipated the significance of the show for Russian viewers, or how it might completely shape the lives of generations to come.

Words

Rachel Segal Hamilton

Diana Markosian: Santa Barbara ICP, New York Until 10 January

Image Credits: 1. Diana Markosian, A New Life. (2019) © Diana Markosian.

2. Diana Markosian, After School. (2019) © Diana Markosian.

3. Diana Markosian, Mom Alone. (2019) © Diana Markosian.

4. Diana Markosian, Hendry’s Beach. (2019) © Diana Markosian.

5. Diana Markosian, The Courthouse. (2019) © Diana Markosian.