As Covid lockdowns got underway last year, Tove Jansson’s 1972 novel The Summer Book suddenly became relevant again. Though written by the Moomins creator nearly half a century before, it now reads as a primer for isolation, detailing how an elderly artist and her granddaughter whiled away a summer on a remote Swedish island. “Rereading it now, this book feels like a survival guide,” noted nature writer Melissa Harrison in The Guardian in April. In July, TED included The Summer Book on its list of summer recommendations.

The characters in Jansson’s book are alone for much of the book, but what comes across isn’t their lack of social contact. Instead, the novel is rich with life, filled with the movement of the tides and winds around the lonely summerhouse, or the tiny shoots and mosses that grip onto the barren rocks. The pair become so delicately attuned to the ecosystem that the landscape becomes another character entirely. “Moss is terribly frail,” reads one section. “Step on it once and it rises the next time it rains. The second time, it doesn’t rise back up. And the third time you step on moss, it dies. Eider ducks are the same way – the third time you frighten them up from their nests, they never come back.”

It’s expected, then, to see a Swedish cabin in Phaidon’s latest title Living in Nature – Johan Sundberg Arkitektur’s Summerhouse Solviken, which was completed in 2018 in Mölle, Sweden, and described by editors as having “simplicity, modesty and wholehearted empathy with its surroundings.” In fact, Living in Nature even includes a series of whimsical triangular cabins inspired by the Moominhouse, set on stilts in the woods in Gjesåsen, Norway, by Espen Surnevik in 2018.

Following on from other titles in Phaidon’s groundbreaking Living in series (deserts, water, mountains and more) this new publication includes designs from all over the world, ranging from the modest to the much more substantial. These are houses in which the organic world has been the primary consideration, informing decisions about everything from the plot size to the materials, views, carbon footprint and geometry within the landscape. Phaidon’s editors note: “These projects take challenging terrains and climates into account, but they do not aim to tame or colonise nature.”

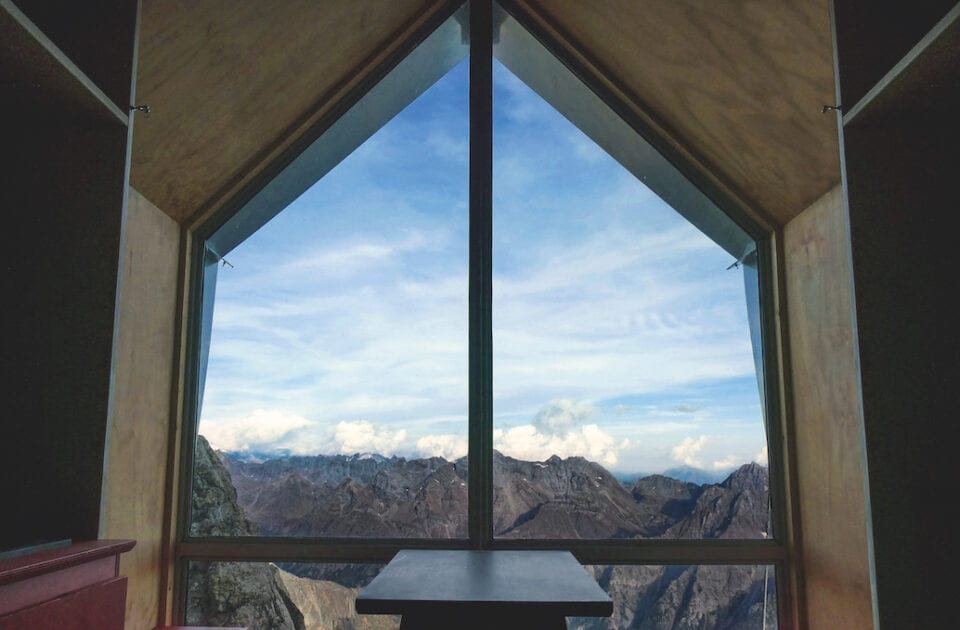

Take Bivouac Luca Pasqualetti, built by Roberto Dini and Stefano Girodo, in Morion Ridge, Aosta Valley, Italy, in 2018. Teetering on a mountain ledge more than 3000 metres above sea level, it’s a simple shelter commissioned to popularise forgotten climbing routes – robust enough to withstand temperatures as low as -20°C, winds up to 200km per hour, driving rain and hail, and snow. Even so, it’s constructed around a metal basement and held in place by guy ropes, which means it can be removed without leaving a trace.

Luciano Giorgi’s Casa Falk, 2008, in Stromboli, Aeolian Islands, has a similar sense of organic luxury, though it’s set in the most uncompromising of places. Wedged between dark volcanic cliffs and the Sciara del Fuocco, a blackened lava scar caused by volcanic eruptions down the northern flank of Mount Stromboli – one of the world’s most active volcanos – it draws on both the environment and the existing architecture, quite literally. Casa Falk is modelled on the typical, white stucco of local homes. However, it also once belonged to Swiss artist Hans Falk; when Giorgi was commissioned to update the building, he restored a fireplace Falk had hewed from concrete and lava stone.

Other locally sourced materials are abundant, with black lava-stone from Mount Etna making up the flooring, and other raw ingredients including chestnut wood from Sicilian forests and marble from nearby Carrara. These materials may be local but they’re also magnificent, and the colour scheme is as rich. The upper floors of Casa Falk look out over the sea and the volcano. Dark bronze window frames are designed to interact with the environment, naturally oxidising with time to change colour. The elements here are undeniably powerful, and the architect has given them space.

Vandkunsten Architects took a similarly sensitive approach to materials with the Modern Seaweed House in Læsø, Denmark, in 2013. The building is on an island in the sea bay of Kattegat, which is famous for its eelgrass-thatched roofs. Unlike wood, seaweed has always been plentiful there, and it also needs no farming because it simply washes up on the shore. In addition, it’s intrinsically waterproof – a great insulator – and durable, lasting about 150 years. First used by the Vikings, eelgrass is attracting renewed interest amongst architects today. Vandkunsten maximised on this innovative – yet age-old – material by stuffing the eelgrass into string-net bags to create bolsters, which they attached in lengths to the façades and roof of the building.

They also packed it into timber crates, placed behind walls and under floors for insulation. Since the house accom- modates two families, seaweed’s soundproofing properties were an added bonus. By working in this way, the architects helped ensure the house has a negative carbon impact – that’s to say, the almost exclusive use of organic building materials, causes the amount of CO2 accumulated within the house to exceed that which was emitted during the production and transportation of those materials.

Brazil’s Catuçaba House, designed by Studio MK27 and completed 2016, also uses local resources, in this case partly for practical reasons – the house is built on a steep hillside in a remote corner of São Luíz do Paraitinga, making transportation a little difficult. Instead, the architects excavated soil to create adobe walls and clay tiles for the interiors, keeping the house cool in summer; the side walls made from rammed earth. The bulk of the structure was prefabricated using FSC-certified cross-laminated timber, which was easy to assemble in this tricky location.

Catuçaba House also features solar panels, a wind turbine and a rain-collection system – though this means that, like three other projects presented in the book, it’s completely off-grid. In this, the project hints at another, compelling theme in Living with Nature – the need to create houses ca- pable of withstanding extreme conditions. When Rob Mills first designed Ocean House in Lorne, Australia, he wanted to build with timber, for example, but a period of bush fires and changes in planning laws meant he had to use concrete.

Meanwhile, the Peruvian Casa Patios, 2018, by Rama Estudio, looks more like the archetypal eco-village – quite literally built into nature, dug into the earth with a green- roof garden on top. The walls are made of bahareque, a material similar to adobe, with straw and soil from the site packed into wood and metal-mesh frames; outer flanking walls supporting the roof are made of heavy stone. “Solid, sheltered, and grounded, Casa Patios is totally in tune with the surrounding landscape,” state Phaidon’s editors.

These houses have a self-sufficient edge that suggests something a little more radical about design and our conception of nature – Covid has taught us that the future is always uncertain, but the effects of the climate emergency are already with us. Ice is melting everywhere and global sea levels already rising at 3.2mm per year (according to National Geographic’s current online statistics). Sea levels are expected to rise between 26cm-82cm by the end of the century, meaning floods will become more likely; hurricanes are likely to become stronger and so too are droughts, and this inevitably means more wildfires. Undoubtedly, everyone will be affected by this destruction, not merely those living on the coast (plus knock-on political changes wrought by, for example, the rapid spike in climate refugees).

In the future, buildings must be able to handle these conditions; designs will need to work in cities as well as in beautiful, remote locations, because – unless new mutations of Covid push us to flee city centres, or depopulate the world to an apocalyptic level – more people will be living in towns. In fact, the European Commission expects some 85% of the world’s population to live in urban centres by 2100, meaning that the urban population will increase from less than one billion in 1950 to nine billion by the turn of the century. “The human race has become a species of town and city dwellers, existing in a landscape of paved streets and structures that keep the natural world at bay rather than belong to it.”

In the next few years, the relationship between humans and local ecosystems won’t be – and can no longer be – an afterthought. It’s therefore fitting (even reassuring) that Living in Nature ends with a project based in Wargrave – a village near London built around both the River Thames and one of its tributaries, the River Loddon. Narula House, completed in 2020 by John Pardey Architects, sits on a flood plain but (like the Moomin-inspired cabins) raised on stilts; when the Thames swells, the house remains well above the waters.

Though Living in Nature is just as appealing as a coffee table book – filled with glossy pictures – the title quietly proposes a radical new approach to the environment: one that’s built on mutual respect and sovereignty. It’s an attitude that hasn’t always held sway in the west but, as Jansson’s novel suggests, this sentiment has always been there; especially in other cultures, with Hinduism (approximately 900 million) and Japanese Shintoism (approximately 90-100 million individuals) both drawing their deities from the natural world, urging a humble regard for other forms of life.

These beliefs informed the projects of Kazunori Fujimoto, the architect behind the 2019 House in Ajina in Hiroshima – a place with more reason than most to be wary of human hubris. Fujimoto’s house faces the sea but also a torii gate, a traditional entrance to a Shinto shrine which symbolically marks the transition from the mundane to the elevated sacred. “I thought it was a courtesy to the shrine to face each other with a proper posture,” he says. “I think you need an attitude of gratitude for being kept in nature – architecture should rationally intervene in the minimum.”

Fujimoto’s words echo the titles of both Living in Nature and The Summer Book, all three suggesting the only route forward being a decentralisation of humanity. Nature is defined as all living things both human and non-human, and it has become evident that, much as we may fight to separate ourselves from the other, we must integrate into ecosystems in a more responsible way, or they will continue without us.

Words: Diane Smyth

Living in Nature: Contemporary Houses in the Natural World is published by Phaidon

Image Credits:

1. Luciano Giorgi, Casa Falk, 2008, Stromboli, Aeolian Islands, Italy. Picture credit: Tommaso Sartori.

2. Roberto Dini and Stefano Girodo, Bivouac Luca Pasqualetti, 2018, Morion Ridge, Aosta Valley, Italy. Picture credit: Stefano Girodo.

3. Roberto Dini and Stefano Girodo, Bivouac Luca Pasqualetti, 2018, Morion Ridge, Aosta Valley, Italy. Picture credit: Adele Muscolino.

4. Luciano Giorgi, Casa Falk, 2008, Stromboli, Aeolian Islands, Italy. Picture credit: Tommaso Sartori.

5. Kazunori Fujimoto Architect & Associates, House in Ajina, 2019, Hiroshima, Japan. Picture credit: Kazunori Fujimoto.

6. Luciano Giorgi, Casa Falk, 2008, Stromboli, Aeolian Islands, Italy. Picture credit: Tommaso Sartori.