A new retrospective of Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988) opens this month at Barbican Centre. Before the show tours across Europe, Aesthetica traces the threads of inspiration which informed his singular practice.

Where does the story begin? Noguchi was born in Los Angeles to a Japanese poet father and American writer mother, spending formative periods of his early career both as an assistant to Constantin Brâncuși, a pioneer of European modernism, and as a student of the master potter Jinmatsu Uno in Kyoto, as well as the brush painter Qi Baishi in Beijing. The multicultural roots of Noguchi’s craft are neatly emblematised in the image of the artist and designer setting off from Paris in 1930 to ride the Trans-Siberian Railroad to the far east, his schooling with Brâncuși at an end and his apprenticeships with his Chinese and Japanese mentors about to begin.

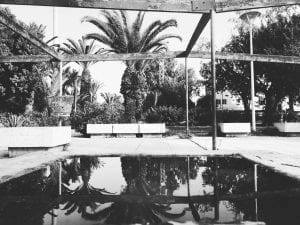

Perhaps the most striking evidence of the educational period that followed can be found in Noguchi’s three-dimensional and land-based practice. Monumental outdoor projects such as the Sunken Garden for Beinecke Library in the USA(1960-1964) and the Garden of Peace for UNESCO’s headquarters in Paris (designed 1953-1955) incorporate elements of the “dry garden” aesthetics of Zen-Buddhist rockeries, like those found at Ryōan-ji and elsewhere across Noguchi’s paternal homeland. The titles of many of his three-dimensional works, meanwhile, suggest a debt to Tantric art, with terms such as Slide Mantra (created for the 1986 Venice Biennale) suggesting a meditative or spiritual function to audience interaction. At the same time, pieces from the period of tutelage with Qi like Peking Brush Drawing (1930) establish an affinity with the fluid, almost calligraphic brushstrokes of the master’s sketches of animals and human forms.

One remarkable aspect of the al fresco element of Noguchi’s practice is how its emphasis on scale and open-endedness – that sense that the viewer can walk into and inhabit the artwork – predicts the rise of monumental US land art across the 1960s-1970s. Indeed, with works such as Sculpture To Be Seen From Mars (1947), the artist seems to anticipate the ways in which extraterrestrial photography would enable the imaginative scope of interventions such as Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty. Like that work, many of Noguchi’s outdoor designs benefit from a majestic aerial viewing point.

On top of this fusion of Eastern and western influences, it is also worth noting how the oeuvre on display at the Barbican straddles the boundaries of art and functional design, and in the same breath between rationalism and the romantic imagination. In the late 1920s, when the young Noguchi was learning stone-carving at Brâncuși’s studio, Paris-based groups and artists such as Cercle et Carré and Piet Mondrian were propagating an art of clean, clinical geometry to counter the dominant impulses of the French Surrealist school, which placed its faith in the unconscious and free expression. With semi-figurative sculptures of interlocking stone, bronze, or wood, such as Figure and Trinity (Triple), the craftsman of mixed cultural origin seems to achieve a union of these impulses. Inspired by the organic rhythms of the body or natural forms, these works are realised through mechanically precise processes.

The entwined lyrical and technological aspects of Noguchi’s early practice preempt the works of industrial and interior design created across the next few decades, particularly after a deal was struck with the furniture company Herman Miller in 1947 – resulting in staples of modernist functionalism such as the Noguchi Coffee Table, with its elegantly twisted leg-piece. Elsewhere in the show we find the iconic Akari series of paper-and-bamboo light shades and, more bizarrely but equally significantly, the Radio Nurse baby monitor created for Zenith Radio Corporation in 1937, the first of its kind.

Arching over all these strands of creativity was a humanist vision invested in the idea of a genuinely useful and life-affirming public art. This was what motivated Noguchi, for example, to become a voluntary inmate in a Japanese-American internment camp at the height of WW2 anti-Japanese racism. It is this unifying and simple sentiment that will perhaps guide viewers through the Barbican show, linking together the many different expressions of a pioneering talent.

Noguchi runs at Barbican from 30 September until 9 January. Find out more here.

Words: Greg Thomas

Image Credits:

1. Isamu Noguchi, Sunken Garden for Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, 1960-1964. Exterior design with Imperial Danby marble. Photograph by Ezra Stoller / ESTO The Noguchi Museum Archives, 01898 ©INFGM / ARS – DACS /ESTO

2. Isamu Noguchi with study for Luminous Plastic Sculpture, 1943. Photograph by Eliot Elisofon The Noguchi Museum Archives, 03766 ©INFGM / ARS – DACS / Eliot Elisofon

3. Isamu Noguchi, Akari 25N, 1968. 117 x 83 cm Photograph by Kevin Noble The Noguchi Museum Archives, 03066 ©INFGM / ARS – DACS

4. Portrait of Isamu Noguchi, 4 July 1947. Photograph by Arnold Newman © Arnold Newman Collection / Getty Images / INFGM / ARS – DACS