The digital age has accelerated humanity’s awareness and connectivity like never before. We move from the micro to the macro – from fly-on-the wall TikToks to satellite images of the Earth – in a single scroll, with each image providing its own viewpoint, from the personal to the global. This powerful experience has opened up new ways of thinking, from open-source resource sharing to citizen journalism. Though, equally, the constant flood of information and opinions can feel overwhelming, leaving us feeling totally powerless.

Forensic Architecture (FA) captures both the tension and promise of the digital age in the context of social justice. Founded in 2010 by Eyal Weizman, the research agency is based at Goldsmiths University in London and has set the discipline of architecture on a whole new trajectory – concerned with “cases” instead of buildings, exploring the intersection of design, law, journalism, human rights and the environment. The group combines architectural skills with digital tools and data, aesthetics and academia, to investigate human and environmental rights abuses, from air strikes and terror attacks to ecocide and acts of chemical warfare.

In fact, it was Weizman’s personal experiences that led him to establish the group in the first place, having grown up in Haifa, Israel, where he witnessed remnants of Palestinian communities. From an early age, he started to understand how the politics of war were inscribed in the urban environment. He went on the study architecture at the Architectural Association in London, going nearly five years without de- signing a building, but working on developing ideas instead. Upon graduation in 1992, he took an internship in Ramallah at the Palestinian Ministry of Planning, where he grasped, on a much deeper, visceral and powerful level, how architecture could service a colonial regime, and how mapping that architecture could be a form of activism rooted in intelligence.

Some 30 years later, Weizman and his team are building on these early lessons in spatial mapping to shed light on human rights abuses, many times in unresolved police investigations. In 2006, for example, Halit Yozgat was murdered at his family-run internet café in Kassel, Germany. Weizman and his team remade the 77 square metre cafe at a scale of 1:1, reconstructing a leaked nine-and-a-half minute police re-enactment of a suspect, Andreas Temme, who had claimed to have not seen, heard or smelt any evidence of the murder whilst being in the building. FA’s in-depth study concluded that the witness testimony was very likely to be untruthful. Furthermore, the results uncovered larger questions about how Germany’s security services monitor and embed them- selves within the country’s resurgent neo-Nazi underground.

This layered, counter-forensic process is like a contemporary archaeology. Images, videos, sounds and pieces of information are mined, unravelled and mapped into “hyper- poly-perspectival” reality. In this state, an incident can be understood from hundreds of perspectives, augmenting a crime scene far beyond the human capacity for interpretation. To achieve this, FA stay abreast of new technological developments. When they started out about a decade ago, each investigation would have a few pieces of related video evidence. Today, they often have hundreds of thousands of clips. “We had to start employing machine learning in order to sift through videos and develop techniques of synchronising high volumes of images into models,” says Weizman.

Whilst physical evidence can be seen as objective, it is important to note that the practice of “forensic architecture” is not an objective operation. Architecture, after all, is social as well as scientific. It is sensitive to human experience, and just as much as the team examines the physical evidence found in buildings, they also consider the “soft” activities happening within it. They are compassionate to victims of trauma and the subjective psychological experience, and this creates a whole new understanding of space. Picture your childhood bedroom or another familiar room in your head – as well as the visual, you can probably recall the smells, sounds and textures. “Our memory is spatially conditioned,” Weizman continues. “If we walk through a building, memories of what happened in particular rooms, corridors and corners spring up in the mind, and we know how to simulate that process.”

In April 2016, Amnesty International and Forensic Architecture travelled to Istanbul to meet five survivors from Sed- naya Prison, near Damascus. In recent years, no journalists or monitoring groups (which report publicly) have been able to visit the notorious prison, or speak with those held there. As there are no images of Sednaya in the public domain, FA’s researchers had to work with the memories of survivors, stimulating their so-called “memory palaces.” Using sketches at first, then reconstructing the scene in 3D models, the spaces were populated with objects and recalled experiences. Fur- ther forgotten details emerged as the model developed.

The imperfect nature of memory is not viewed as a weak- ness, but a tool for understanding. “Things become complicated because trauma distorts space,” says Weizman. “Corridors that are short become long; places that are rectangular become circular; the number of people and sounds gets amplified. These memory errors are very interesting for us. They are more informationally rich than a correct, cartesian description of space, because the error contains both the space where things happen, and one’s own subjectivity of trauma.” “Socialising” space with these enriched experiences results in what FA calls “situated testimony” – beyond a physical reconstruction of space, the multi-sensory “genius loci” of an event is reconstructed. This scientific process that accounts for both evidence and empathy is another one of FA’s tools. “Importantly, we are not like a normal human rights group,” says Weizman. “We are based in a university, so our mandate is the development of new ideas. We take cases because we care and want to contribute to particular struggles, but also because they allow us to develop our technique further.”

Today, FA receives many requests, and specifically chooses cases that could spark wider political change – performing a type of geopolitical acupuncture. Take the case of Halit Yozgat: one of 10 murders committed across Germany be- tween 2000 and 2007 by a neo-Nazi group known as the National Socialist Underground. Or in the case of Sednaya Prison where, since 2011, thousands have died in detention facilities operated by the Syrian government, and even more have been tortured and ill-treated in violation of interna- tional law. In both, FA’s work helped to expose deep-rooted structural crimes of official police and government systems.

This has extended to the horrors of the Ukraine War, specifically investigating the missile strike on the Kyiv TV tower on 1 March 2022. Weizman notes: “The missiles landed on the territory known as Babyn Yar, the site of one of the worst massacres of the Holocaust. Historical references, particularly ones related to WWII and the Holocaust, have been continuously weaponised as part of Russia’s propaganda machine. Given their claims about the ‘de-Nazification’ of Ukraine, the destruction of one of the Holocaust’s most significant symbolic sites is particularly ironic. Our investigation sought to examine the confluence of past and present in this fraught landscape, drawing together a detailed analysis of the recent strike on the TV tower and a spatial reconstruction of the Babyn Yar site – a complex ravine system that used to run through this part of Kyiv. By excavating the historical layers of the Babyn Yar site, we have been able to locate massacres and the multiple attempts made to silence their memory.”

For this project, FA collaborated with the Centre for Spatial Technology, based in Ukraine, to investigate the history of several sites of Russian bombardment. “Our attempt was to follow the bombs into the ground they are blasting, but follow them not only in space but also in time. Every ruin used to be a building, and it exists within a social and urban context that is rich and densely detailed, and can tell us about what Ukraine was.” Using historical and cultural intelligence as a form of activism aligns well with the ambitions of many art institutions. The investigation into the Russian strike on the Kyiv TV Tower is on view for the first time at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, as part of the groundbreaking programming series The Architect’s Studio.

Importantly, FA shows how architects can use their skills in alternative ways, and this is recognised by Louisiana. “The environment is suffering from the building industry, which has the biggest carbon footprint. Should architects be build- ing more? Perhaps they can work with old structures and landscapes instead, but we also have to work to expand the field of architecture, as well as asking what are the boundaries of this field?” says Mette Marie Kallehauge, Curator.

The exhibition, in turn, gave FA the opportunity to further reflect on the relationship between evidence and testimony, and to examine the human and material witnesses at the core of their work. Eighteen key projects show how both the physical and meta-physical can be constructed in space. Specially built for the exhibition are two 1:1 models of crime scenes that can be explored by visitors; the case of Halit Yozgat, and the case of a drone strike in Miranshah, Pakistan, which killed several people. Weizman sees the exhibition format as another tool available to him, presenting a case in a new way. “In each forum there are things that you can say, and things that fall out – whether it is The New York Times, a courtroom, in academia and likewise in an art space. It’s important to take a single piece of evidence through as many fora as possible, because in each one you would see other aspects,” he notes.

In the digital age, it is easy to fall into binary traps where images and videos can be presented as evidence, contexts lose dimensions of understanding, and witnesses are examined without compassion for the human experience. In every aspect, FA disperses these binaries with its multi-disciplinary nature, critical questioning and interest in subjectivity – important skills that are only becoming more necessary to living today. Weizman continues: “Forensic Architecture has been a part of an opening of a new field within architecture and aesthetic practices. I see the techniques we have developed being used now not only in journalism, but also by human rights groups. FA has given architects the potential to intervene in issues in a way that other disciplines cannot.”

Words: Harriet Thorpe

The Architect’s Studio: Forensic Architecture Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek | louisiana.dk

Image Credits:

1. Exhibition view(s) of Terror Contagion Forensic Architecture presented at Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, 1 December 2021 – 18 April 2022. Photo: Richard-Max Tremblay.

2. Exhibition view(s) of Terror Contagion Forensic Architecture presented at Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, 1 December 2021 – 18 April 2022. Photo: Richard-Max Tremblay.

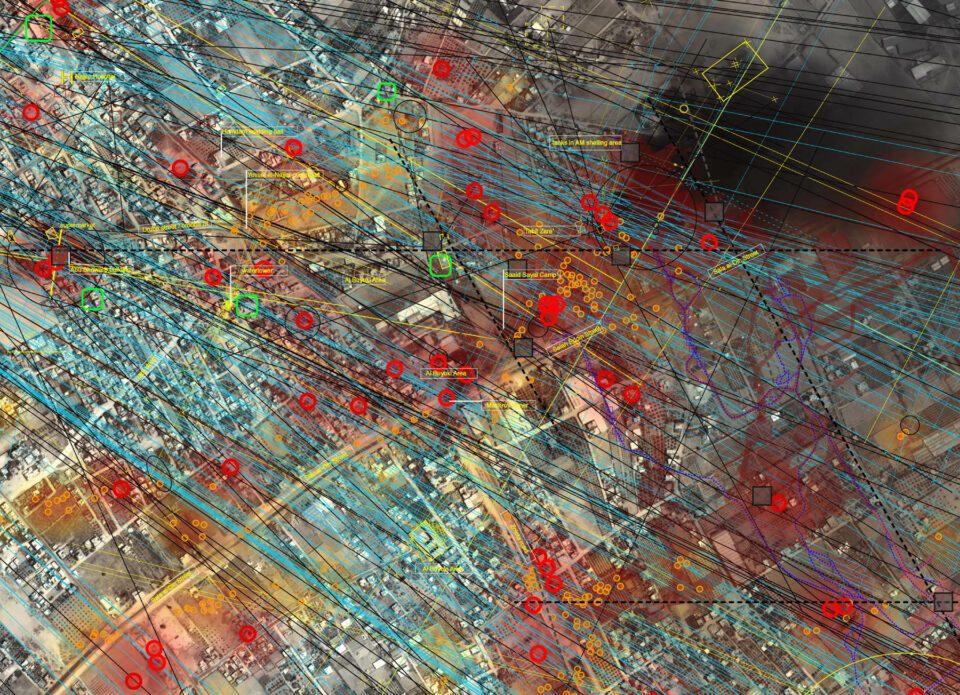

3. Forensic Architecture, The Bombing of Rafah, 2014 – Multiple images and reconstructed bomb clouds are arranged within a 3D model of Rafah, Gaza.

4. Still from The Beating of Faisal al-Natsheh, 2020. Superimposition of the models from the three witnesses Forensic Architecture interviewed as they describe a convoy of soldiers escorting arrested Palestinian civilians to a militarised checkpoint in Hebron. (Forensic Architecture/Breaking the Silence, 2020).

5. Exhibition view(s) of Terror Contagion Forensic Architecture presented at Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, 1 December 2021 – 18 April 2022. Photo: Richard-Max Tremblay.