Photographer Soren Solkær (b. 1969) is best known for moody, stylised portraits of musicians, actors and filmmakers – from Amy Winehouse to David Lynch. But for his most recent project, Black Sun, he has left the human world behind, tracking the migratory flight paths of starlings across Europe to capture the extraordinary patterns made by their murmurations in the sky.

A: How did you start out photographing starling murmurations? I understand you grew up in rural Southern Denmark where you saw this a lot?

SS: That’s correct. I grew up in a place where there was nothing to do, so every winter I would sit by the window recording the birds when they came into my garden. Then I spent more than 25 years trying to escape the countryside, working in Copenhagen, London, New York, LA and Sydney. But there was a point three or four years ago, when I’d just finished a huge 25-year portrait retrospective, when I thought: this is the time to try something else. So, I headed back to the south, to the marshland where I come from.

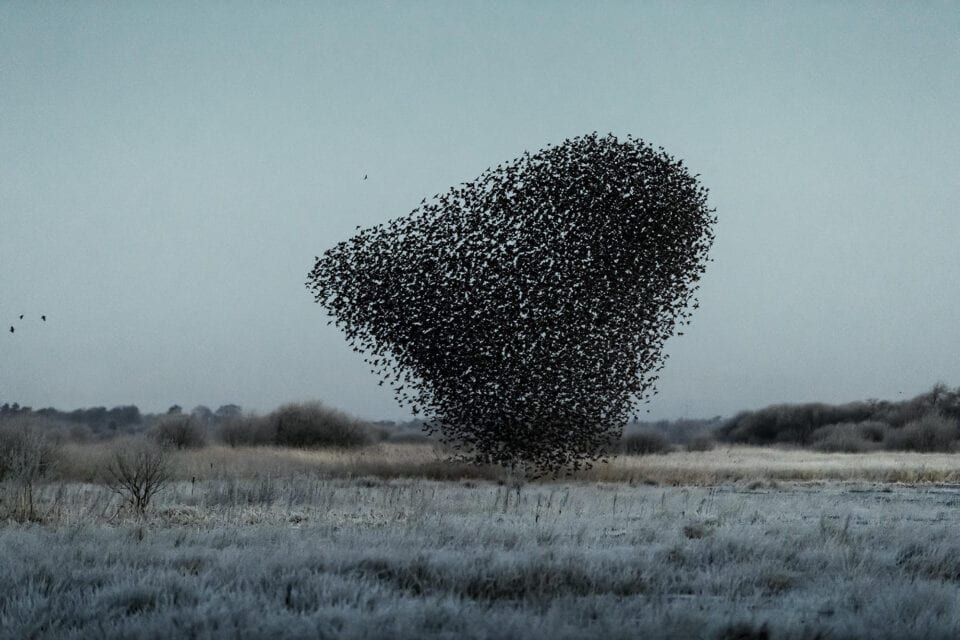

I initially thought I would dedicate a week to the project, but I ended up being totally blown away by how exciting it was being with the birds and photographing them. I got one picture in that first week that really looked like a Japanese ink drawing, and I thought it was really interesting aesthetically. The opportunity to see the starlings in Denmark was very seasonal though. So, I started researching and found that this phenomenon also happens in the UK, Germany, Holland, Rome and Catalonia. I started following the birds along their migration paths and that led me to a lot of new territories.

I’ve probably spent 100 nights doing this – most of the photographs are taken at night, prior to the birds nesting in the reed forest. But it’s really a patience project: I would say that 80 per cent of the work in the book is probably from five or six nights. Most nights there are a lot of birds flying around, but it requires a bird of prey to get the flock going and creating shapes and images in the sky.

A: Are the landscapes important to you as well?

SS: The very graphic winter landscape really fascinates me, because my inspiration for this project has been mainly Japanese landscape art – particularly woodblock – and I think the winter landscape has really lent itself towards making these very graphic images. I had a show with this project last year in Kyoto, and I think 50 per cent of the people who saw it didn’t think it was photography: they thought they were ink drawings on paper. The audience at the show related to the work on a really deep level, even though they don’t have the phenomenon of starling murmurations in Japan.

A: What are some other artistic influences on the project?

SS:There are several influences. The big landscapes really remind me of old Romantic painters, like Caspar David Friedrich, and then I have some images that really look like abstract expressionist paintings. I think because the paper that I print on is Japanese handmade kozo washipaper – juniper fibre-based handmade paper with a very heavy texture – the work doesn’t really look like photography. It’s almost like printing on some very organic textile, and I think that gives the work an even stronger relationship to painting.

A: The images convey a strong sense of the birds’ collective, unconscious intelligence. Is there an ecological message in the work about the value of non-human life?

SS:Absolutely, and not only starlings. Around three years ago I got a little cottage by a fjord an hour from Copenhagen, and I’ve started spending much more time in nature. Also, it really seems to me that they are trying to communicate. The pictures the birds paint on the sky: many of them are really recognisable to human beings. Interestingly, I read that in ancient Rome they would place an oracle on the Aventine Hill in the season when the starling were there, and they would interpret the symbols made by the starlings, thinking that it was the gods speaking to them. I have had experiences like that, where I feel that these can’t just be totally arbitrary shapes.

A: You mentioned Caspar David Fredrich, and you have also referred to the spiritual quality of the work. Do you see the images as having a place in the tradition of Romantic landscape art?

SS:I think so, and especially a connection to Friedrich, the way that the human being became very tiny in his work, and the idea of God infusing nature with energy. There was an incident this year, in February in Holland, when I was standing watching a sky that was totally black, 360 degrees black with birds. It went on for twenty minutes and it was highly dramatic, as was the sound of it. There was a very old woman standing next to me whilst I was watching this. We were both in awe of it, and when the birds had finally gone to rest in the reed forest we were both still for a couple of minutes, and then she turned to me and said “that was the most beautiful thing I’ve seen in my whole life!” I started crying and I said, “me too!”

Greg Thomas

All images courtesy of Soren Solkaer.

sorensolkaer.com

IG: @sorensolkaer