Shirin Neshat studies individual and cultural gestures, representing some of the most unstable, charged and conflicted moments of recent history.

“Every Iranian artist, in some form, is political. Politics have defined our lives.” This statement, made by Shirin Neshat (b. 1957), goes some way to explain how her work is, by its very nature, an act of defiance. She was born in Iran but has spent much of her life in exile in the USA. Through this experience, she has relentlessly engaged with the world through lens-based media, exploring universal themes of displacement, oppression, gender and identity. Perhaps more than any other living practitioner today, she has demonstrated the power of art to deconstruct the political climate – including Trump’s increasingly aggressive and nationalist America.

Neshat’s journey began back in 1975, when she was sent to California aged 17 to finish her education. Since then, she has produced numerous acclaimed and compelling series that span photography, video and feature films. These interdisciplinary works have exhibited at some of the world’s most revered institutions. Further to this, she was awarded the First International Prize at the 1999 Venice Biennale, the Infinity Award from the International Center of Photography (2002) and the Hiroshima Freedom Prize from the Hiroshima City Museum of Art (2005), amongst others.

Now, Neshat’s first major show on America’s west coast opens at The Broad, Los Angeles. “I Will Greet the Sun Again shares the beautiful work of an individual who gives voice to outsiders and exiles who have left their countries in the wake of political conflict,” says Joanne Heyler, Founding Director of The Broad. “At a turbulent time of highly charged civic discourse surrounding immigration and nationalism, this survey will offer an opportunity to consider new viewpoints and ideas, and for rich, open exchanges that examine our social, cultural and political conditions.”

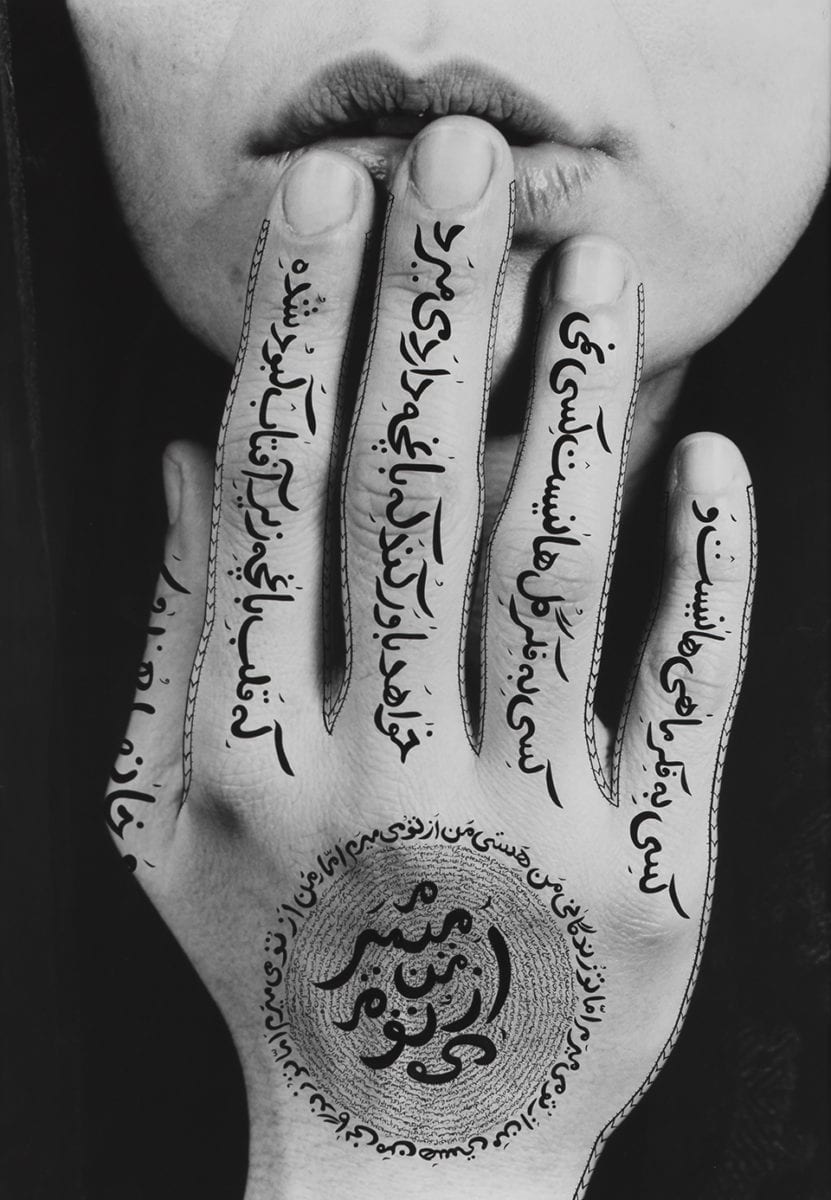

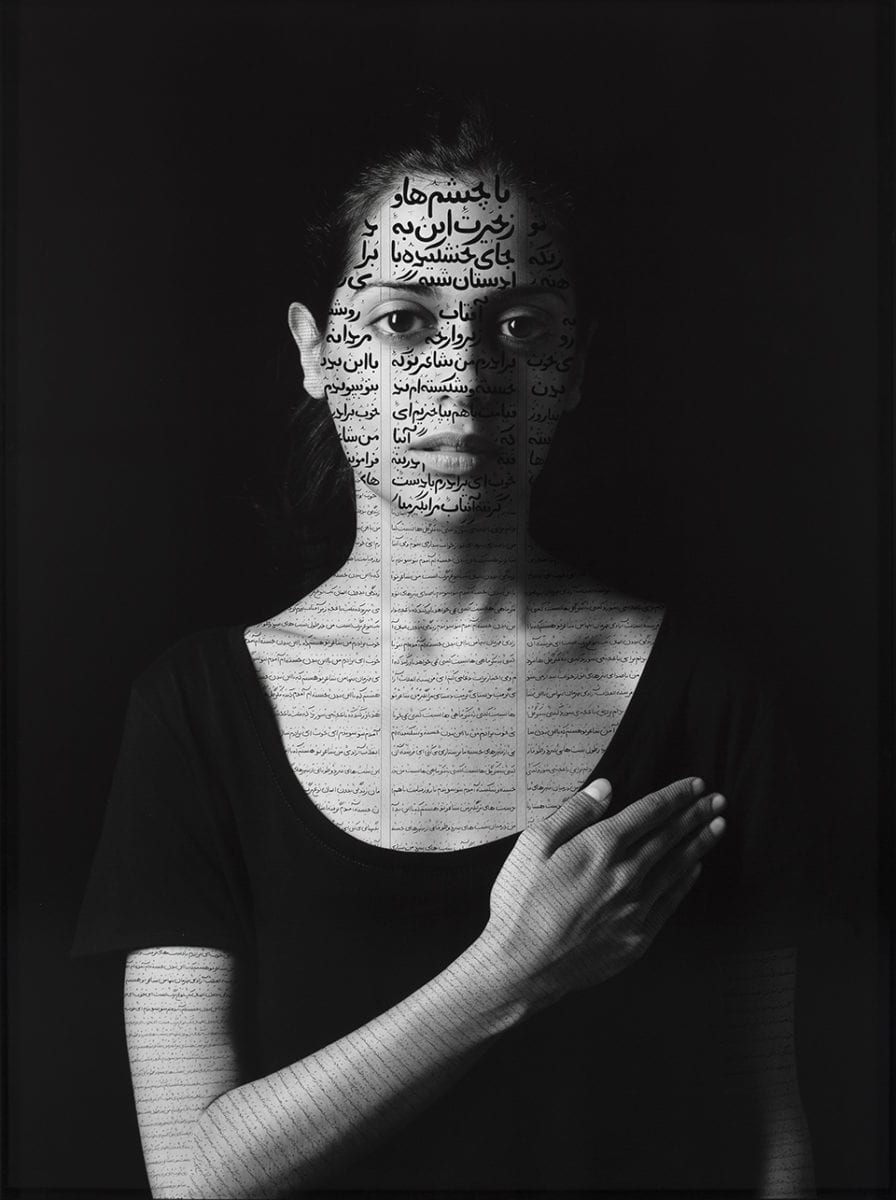

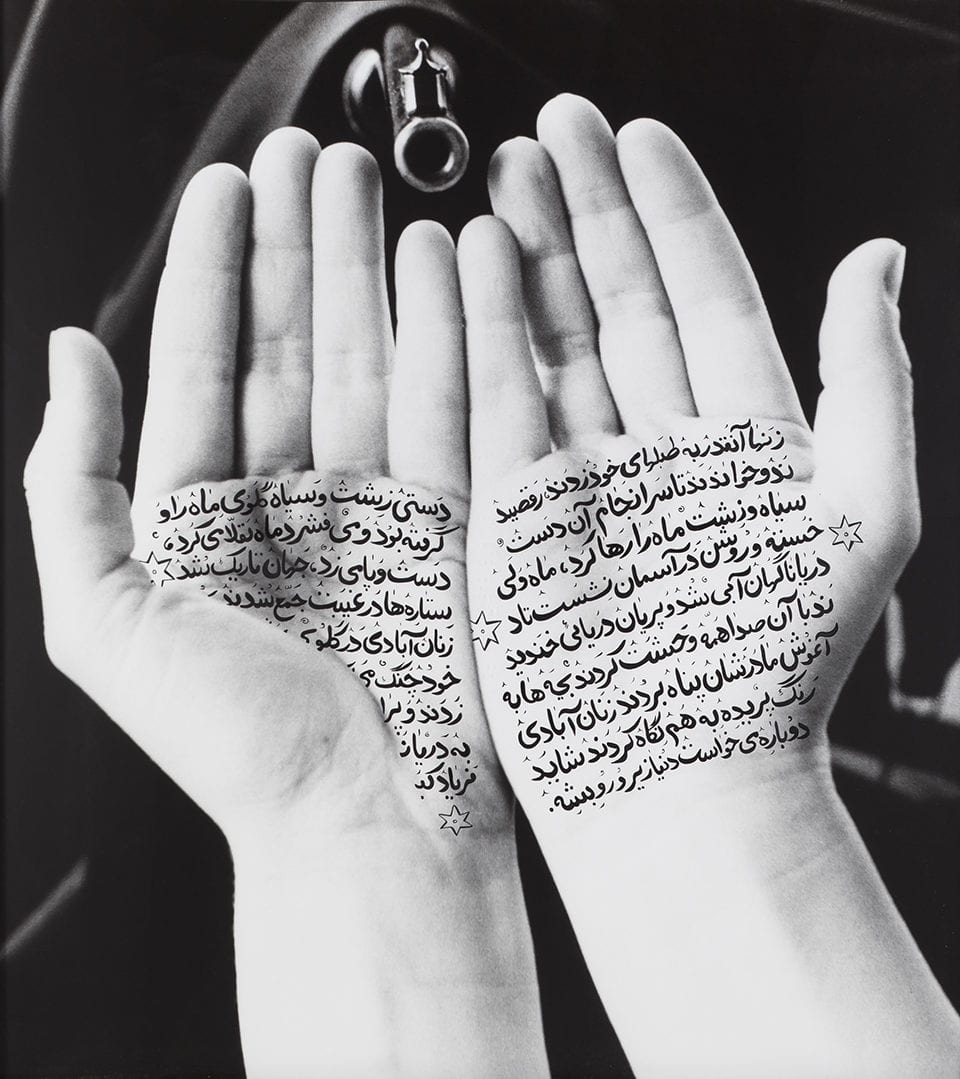

As this exhibition shows, Neshat’s enduring appeal has been her ability to address both the particular (her experience in exile as an Iranian woman and American citizen) and the universal (larger themes that tie into the human condition as a whole). Indeed, a key marker of her practice is her ever-broadening subject matter. In early pieces, such as the now iconic Women of Allah (1993-1997), Neshat is very close to a specific moment. The three-part photographic series depicts the lives of Iranian women and their relationship with the veil, which Neshat surveys as both pervasive and atmospheric. The precision of this project was born out of rediscovery – looking back to her home country during the early 1990s. Due to the turbulence of the Islamic Revolution (1978-1979) and the Iran–Iraq war (1980-1988), Neshat continued to live outside Iran during that period. But after 12 years away, she returned, and was bewildered by the seismic transformations that had taken place – changes which those close to her were readily accepting. “She was travelling to Iran between 1990 to 1995 and was able to enter and leave freely,” says Ed Schad, Exhibition Curator. “She was talking to family members, scholars and all sorts of voices.” The radicalism she witnessed ignited in her a need to create, and heralded the start of a new artistic life.

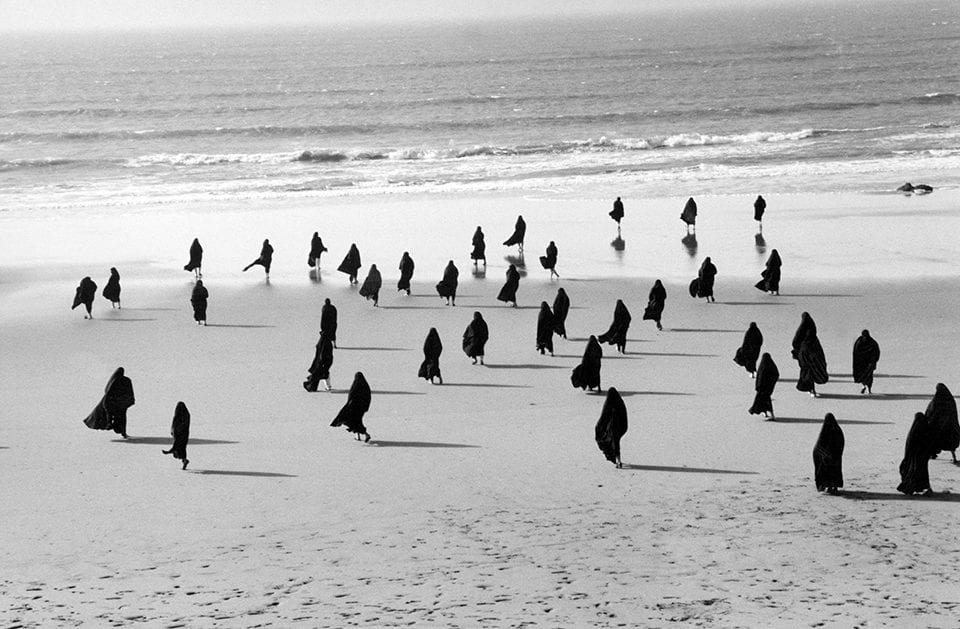

The film Turbulent (1998) continued to express women’s search for freedom. It won the Venice Biennale’s top accolade and cemented her as one of the most talked about contemporary artists. It was also a departure from photography – the first of many huge formal risks that would punctuate a celebrated career. Indeed, the decision to harness different media, across a range of disciplines, has become as nomadic as Neshat’s cultural interests. “She became known for photography then turned to filmmaking, then from gallery installations to feature films, then back to photography – but under changed terms,” says Schad. “Now her photo installations are cinematic. They function as small countries: huge ideas that work together inside a single space.”

Following an official ban from visiting Iran in 1996, Neshat started to focus on a wider perspective outside the definition of being inherently Iranian, moving to reflect upon her experience as an American citizen and beyond. “She was looking for larger frameworks that aren’t so specifically rooted in contemporary events in Iran,” says Schad. “What she calls a ‘universal turn.’” The video installation Tooba (2002), which is one of the “hinges” in the exhibition, is an example of this. It was made in response to 9/11 and is, in Neshat’s words, “an examination of the symbolic significance of the garden in the mystical traditions of Persian and Islamic cultures.” In the Quran, the Tuba tree symbolises blessedness as it extends its canopy of branches to enclose and protect Muslims around the world. The film was shot in Mexico, using Mexican actors, and therefore straddles both this ancient cultural symbol and also the contemporary needs of all displaced people who seek refuge or asylum. “She’s been associated with biographical artworks but it’s her intention to make [projects] applicable to wider stories that a lot of immigrants and exiles share,” explains Schad.

In this way, Neshat’s practice speaks to history but is not defined by it. At The Broad, Tooba plays in the same room as the video installation Passage (2001), which she was working on when 9/11 occurred. “I think that Tooba and Passage represent an extraordinary turn from individual private experience to a truly outward-facing and universalist impulse,” says Schad. “Those films are very mysterious, they are grounded in symbolism, but they also set up a viewer for the rest of her career. “In previous films – whether it’s Possessed or Turbulent or Rapture – in which men and women are kept relatively separate, they come together in Tooba and Passage to look for sanctuary collectively. Indeed, all of the different voices and political moments can be boiled down to the idea that everyone needs a version of home and everyone experiences a sense of profound loss.”

This is not the only point in the show where multiple installations are shown inside a single room. Turbulent (1998) and Rapture (1999) are also “talking to each other” in the same space. Made within a year of each other, both use metaphor as a means to subvert censorship, saying two things at once whilst asking viewers to “hear between the lines.” Turbulent shows a male and female singing in an auditorium. Since there is a law in Iran prohibiting women from singing in public, this is already a basic electrifying point. However, the longer one watches, it is evident that the “turbulence” could exist anywhere. “Some of the themes here – the relationship between men and women enacted by law, social custom and religion – are more widely applicable than simply a questioning of regulations,” adds Schad. Neshat’s figurative practice has roots in the history of Iran and Persia, where they have long been engaged for political purpose. “A poet like Hafez, for example, is notoriously difficult to translate because of the various textures that his symbols could mean, which are open to wide interpretation,” says Schad. Neshat constantly draws on this legacy – sometimes evoking particular poets such as Forugh Farrokhzad (1934-1967) – and invites a meditation on intangible memory, experience and imagery rather than cold, hard truths.

The fact that this retrospective is held in Los Angeles is particularly important to note. California was the first place that Neshat lived in America and she didn’t feel welcome there, later escaping to the more liberal New York City. It was the era of Ronald Reagen, when the anti-Iranian sentiment that permeated society was keenly felt. Southern California is home to the largest Iranian diaspora in the world, with estimates of between 300,000-500,000 people. But the show’s significance is bigger than Iran. As Schad states: “So many people have migrated to southern California – there are Latin Americans but also a massive community from Vietnam, as well as a large community displaced by Hurricane Katrina – so we have our own homegrown exiles coming to Los Angeles. It’s a sanctuary city.” To acknowledge that, a large Tuba tree has been installed right in the middle of the exhibition. “We hope it will be an opportunity to think about the idea of refuge and asylum,” adds Schad. “There are so many complicated and brutal situations all over the world.”

In recent series that have not been seen before in American museums – The Home of My Eyes (2015), Roja (2016), Land of Dreams (2019) – Neshat uncovers the psychological frameworks that leave people trapped by nationalistic discourse. Roja, part of a trilogy known as Dreamers, is a visualisation of an ethereal world, focusing on feelings of rejection from one’s homeland. The Home of My Eyes looks at the historical relationship between the people of Azerbaijan and Persia. “It speaks to the bonds that hold us together,” explains Schad, “the deeper heritage not confined to political borders – a bonding that extends across the world.”

Meanwhile, Land of Dreams, made specially for The Broad, is a two-screen video installation that follows the journey of a fictional Iranian American photographer, who is travelling through western states, under the pretext of taking portraits. “In fact, she’s collecting memories for a mysterious colony,” says Schad. “And so those suspicions that she often feels as an Iranian American – or that anyone feels in a situation where they can be seen as a stranger inside a country they call home – are being satirised here.” The concept invites comparisons to the well-known totalitarian and dystopian worlds imagined by Orwell and Kafka, which, somewhat ironically, are regularly being referenced in popular discourse concerning today’s fragile world.

At its heart, I Will Greet the Sun Again shows that Neshat’s relevance goes far beyond her specific associations with Iran. The works ultimately demonstrate a transcendence from homeland – she has moved on. Quoted in 2017, she went as far as saying that she’d lost “that incredible desire to go back. The good news is I’m over that,” said Neshat. Schad agrees: “I think the exhibition will show how her concerns have expanded exponentially over the course of 30 years. People will be surprised how prescient and precise her observations are – not of Iran, but of the USA. We have to look at ourselves and these major bodies of work – made in the USA about the USA. They are told through the lens of one of our own citizens – an individual who emigrated here from Iran and was eventually exiled whilst living in the country. That concept could not be more resonant now.”

Alexandra Genova

I Will Greet the Sun Again, 19 October -16 February

The Broad Museum, Los Angeles.