Rodney Graham’s exhibition at Lisson Gallery, London, uncovers the sculptural and cinematic nature of his practice, and the continued influence of music, painting and film upon his work.

In 1991, Canadian artist Rodney Graham (b. 1949) created a bookmark, typeset with text written by himself, to be inserted between pages 56 and 57 of an original first edition copy of Ian Fleming’s book Dr. No. (1958). Seamlessly continuing from Fleming’s page 56, Graham’s intervening page introduces a new sequence in which a poisonous centipede traverses up James Bond’s naked body. The use of literature and other art forms as source material is key to the photoconceptualist tradition of the Vancouver School in the late 1970s and 1980s: a group defined by a style of photography in which moments from art history or fine art are replicated. Although Graham is strongly associated with photoconceptualism, and this categorisation is fitting for much of his practice, it is specifically his expansion of literary, filmic and historical material in his work that defines him as an artist.

Following his acclaimed retrospective, Through the Forest, at MACBA, Barcelona; Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Basel, and Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, in 2010-11, a new exhibition of Graham’s work at Lisson Gallery, London, focuses on the artist’s recent photographic work. Each one of the six light boxes in this show depicts scenes that linger, freeze-framing moments of peculiarity, paradox and poetry. Curator Silvia Sgualdini says: “The pieces in this exhibition are replicas of specific moments that have been reappropriated from observations, paintings, books and films.” The events in Graham’s photographs, such as a painter taking a cigarette break on stilts in his work clothes, are bizarre, yet still perfectly possible and grounded in reality. They portray the brief happenings in life where not everything matches, and where things – scenes, people, objects – seem to go through a process of displacement. The paintings and film sequences to which some of the works refer also share this feeling of dislocation, illustrating figures, activities or facial expressions that seem estranged from their surroundings. As in the work Dr. No, Graham’s photographs select specific moments in film and fine art – moments, often, of idiosyncrasy or humour – and build upon them, sometimes stretching them endlessly.

This is exemplified in the work Sunday Sun (2012). Set in 1937, a small light box depicts a figure sitting up in bed, completely obscured by a large newspaper he or she is holding up, open, in front of his or her face. Sgualdini explains: “What makes Sunday Sun interesting is that you can see, when you observe closely, that the newspaper is being held up by two hands that are not actually from the same pair. Each hand belongs to a different person. It’s a sketch that Rodney took from Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes (1938), in which two of the characters have to share a small room in an inn with only one bed. The following morning, there is a scene in which it appears that one of them is in bed reading the paper, but in actual fact both characters are sitting next to each other behind the same newspaper.” The uncanny character of Sunday Sun has its roots, of course, in the original Hitchcock scene. However, despite not being responsible for the comedy in this work, Graham is accountable for the preservation of the moment – the singling out of the sequence, the extraction of it from the film and the expansion of it. Hitchcock’s subtle joke is held in a state of suspension by Sunday Sun at the pivotal point in between believing there is only one figure and seeing that there are, in fact, two. While in the Hitchcock scene, the film itself reveals the reality (or punchline) of the joke, in Graham’s piece the viewer must comprehend it for themselves. Through translating the amusement of The Lady Vanishes from film to photography, Graham is changing the very time frame from within. The moment is paused in its entirety, and the joke lasts for as long as it takes for the audience to grasp it. That said, the visual exuberance of Sunday Sun – bright colours, floral wallpaper and bedding, plus the extremely busy cartoon pages of the newspaper (the only pages visible to the viewer) – distracts so much from the two hands on either side of the spread that the joke probably goes completely unnoticed. Graham’s homage to Hitchcock is, in a sense, a bookmark for The Lady Vanishes. The suspense is continued indefinitely.

This borrowing from, and creating around, other art forms is not limited to Graham’s practice. His contemporary, Jeff Wall, also replicates elements of other forms in his photography. A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai) (1993), for example, is a re-enactment of Katsushika Hokusai’s Travellers Caught in a Sudden breeze at Ejiri (ca. 1832). The traditionally dressed rice field workers in Hokusai’s print are transformed, in Wall’s photograph, into tie-wearing Westerners in the countryside. Wall’s piece is comparable to Graham’s Cactus Fan (2013), a photograph that sees 19th century German romantic painter Carl Spitzweg’s The Cactus Aficionado (1856) adapted to the setting of a university science lab. These two works are easily comparable due to the fact that both mirror the core concepts of esteemed paintings. However, the similarities between Wall and Graham are often disputed. The appropriation of high art concepts in photography is a theme associated with the photoconceptualist tradition of the Vancouver School – a convention both artists are associated with. This categorisation of artists, however, is problematic; the photoconceptualist theme of referencing and replicating other art forms, evident in A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai) and Cactus Fan, did not arise from a preference of style or concept but rather from the anxiety that photography was suffering. It is often argued that the only things Graham and Wall have in common are their similar background and the fact that they both came to prominence when photography was redefining its role in fine art. Sgualdini explains the connections between Graham and the other artists of the Vancouver School: “I think that Rodney and these artists share a mutual influence and conversation due to their close background and concerns, and, of course, they have a natural exchange of ideas. But I think that, even though they are using light boxes, and even though several of the artists at this time set up scenes from observations and pre-existing paintings, they all follow different, personal lines of enquiry.”

Today, with photography thriving in the fine art world, the literary, filmic and painterly themes in Graham’s ongoing practice are no longer linked to the preoccupations of photoconceptualism, despite having partially stemmed from them. Observation, translation and adaptation are employed by Graham in his photographic work to create scenes of displacement and absurdity as well as to stretch to its limit and expand upon source material. Cactus Fan is an example of this. In this image, the stern scholar and dull colours of Spitzweg’s painting are transformed into a figure wearing a lab-coat, pondering over a cactus adorned with balloons in a science lab. The cactus, of course, seems completely out of place in the clinical white space. “Whereas some of his works have a more direct relation to reality (for example to things that the artist has observed personally), others refer to moments in literature or things that exist in paintings, and these moments can appear more unusual due to the contemporary settings,” says Sgualdini. This relocation in Graham’s work – the often conflicting situations, settings, objects and characters – explores how the role of the artist can be understood by what surrounds him. His translation of the subject built upon Spitzweg’s solemn and pondering work to create a humorous result that ignites the imagination.

Graham has control over the original events and scenes that are depicted. He alone decides how he wishes the source material to be translated, portrayed and understood. Sgualdini comments: “All of the works collected and referred to have Rodney in them. Due to the fact that each image is purposefully constructed, every object in every piece has a reason to be in the frame.” The resulting images are pictorial representations of the ways in which Graham views and understands the original source material. This element of restrained control and exacting choreography is extended, even, to the subjects of each photograph: the protagonists, all of whom are played by Rodney Graham. “He always acts as the main character in his work. He represents characters – impersonates them – despite not having any personal relationship to them,” says Sgualdini. Graham acts as a prop in his works, dislocated in the times and lives of other people: Hitchcock characters and Spitzweg subjects. Compared with the works of other artists, such as Cindy Sherman, who also appear in their pieces, Graham’s presence in his photographs is unobtrusive and understated. Sgualdini explains: “There isn’t really any sense of masquerade in Rodney’s work, as you might find in Cindy Sherman’s photography. In Sherman’s work, she appears in all the images, but she is never herself. Somehow, the characters who Rodney impersonates do not require him to be in disguise or to act; they’re an extension of him.” Again, the theme of enlargement is relevant. This time, however, it is the artist himself who is growing.

One particular work, especially, captures the artist as a character, but the lines between reality and fiction are truly blurred. Sgualdini comments: “There is one light box called Pipe Cleaner Artist, Amalfi, 1961 (2013) which shows a painter sitting in a studio working. Rodney made a number of paintings that were originally designed as props to feature in the light box. However, as he was working on them, they developed into independent works so they exist now alongside the light box and as an extension of it.” Pipe Cleaner Artist, Amalfi, 1961 was inspired by the 1930s Man Ray photograph of Jean Cocteau working on a hanging pipe cleaner construction of the type he made for the film Blood of a Poet (1930), as well as a photograph of Danish artist Asger Jorn in his studio in 1961. The paintings are a product of the characters that Graham embodies, becoming an amalgamation of the real artist and the fictional one.

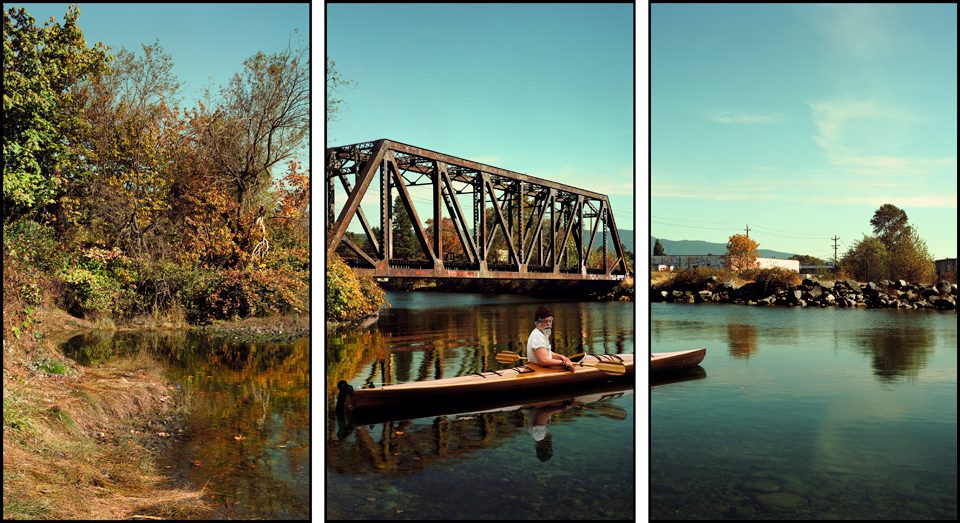

Although all of the works in this exhibition feature Graham as a protagonist, not all of them are absurd or witty. Paddler, Mouth of the Seymour (2012-2013) is a re-enactment of a painting entitled Max Schmitt in A Single Scull (1871) by the American Realist Thomas Eakins. The painting depicts Eakins’ friend, Schmitt, resting after a race on the Schuylkill River near Eakins’ home in Philadelphia. In the description of the work, Graham writes: “I have always admired this work and long wanted to adapt it to a photograph in a contemporary setting. Recently, I found a local equivalent of the bridge which figures in the back of the Eakins painting, and I decided to shoot the piece using myself as the model (as I always do).” Graham, in a sense, is prolonging the relevance of the original Eakins painting by adapting it into a photograph; furthering its reach and values, and pushing them forward into contemporary times. The scale of this work, plus the division of it into a triptych, makes the piece, when hung, appear like a window. Jeff Wall’s The Storyteller (1986) and Stan Douglas’ Abbott & Cordova, 7 August 1971 (2009) have similar effects. These works, along with Paddler, Mouth of the Seymour, appear to be frozen in reality, expanded into a simulated space. Evenly lit by the light box backlights, the pieces, rather than simply looking like photographs, resemble real scenes suspended in time.

At every turn in Graham’s work, he creates a form of intervention. In Dr. No, Fleming’s text is interrupted and then looped. Similarly, Hitchcock’s joke is infringed upon and left suspended in Sunday Sun, Spitzweg’s subject is reinterpreted in a contemporary context in Cactus Fan, and even space and time are intervened upon in the larger window-like works such as Paddler, Mouth of the Seymour. Like Dr. No, the photographic works are all, in a sense, bookmarks too, continuing from, expanding upon and intervening in calculated moments of space, reality, film, art and life.

Rodney Graham continues until 29 June at Lisson Gallery, 29 Bell Street, London.

For further information visit www.lissongallery.com.

Claire Hazelton