Review by Elisa Caldarola

Nothing is Forever celebrates the renewal of South London Gallery, based in a late 19th century building in Southwark. It is not an exhibition of works in a gallery, but of works on the gallery. The works are mostly directly painted on the walls of the gallery itself and are not “forever”, because they will be painted over at the end of the show. The works are on the gallery also in a more abstract sense, because they celebrate the spaces of the building.

South London Gallery is at the same time an intimate and a public space: it is a big building, but not bigger than many of the London town mansions. The Outset Artists’ Flat on the second floor –where artists in residence will be hosted from October 2010 – highlights the house-like character of the gallery (on this occasion the flat is open to the public). On a similar note, one of the gallery’s café rooms has a single long rectangular table with 14 seats around it. It looks like the place where a typical Victorian family would have dined. The café is embellished by Paul Morrison’s work Asplenium (2010), a wall-paint in gold foil of beautiful botanical motifs in dialogue with the outside garden.

A more traditional exhibition space is to be found in the large downstairs room with various works focussed on language by acclaimed American conceptual artists Robert Barry and Lawrence Weiner and British artists Fiona Banner and Mark Tichtner. Barry’s work is the landmark Telepathic Piece (1969-2010: it was originally conceived for an exhibition in San Paolo, but was never shown or printed out in the exhibition catalogue), referring to a series of possible objects of telepathic transmission: desires, volitions, feelings, emotions, concerns. It sounds like a semi-ironic user’s manual for the enjoyment of the exhibition space. Tichtner’s is a slogan painted over a colourful pattern borrowed from the Victorian decoration of the gallery’s floor. The slogan itself is the result of a twofold borrowing, from the words of 19th century inventor Nikola Tesla (‘Let the future tell the truth’) and the World Social Forum (‘Another world is possible’): a cross-fertilization much in the spirit of the gallery’s values. In the Clore Studio – a space to be dedicated to participatory activities – Lily van der Strokker, Dan Perjovschi and David Shrigley further address political themes, with works full of wit and a fresh graphic.

On the stairs to the upper floors Gary Woodley has traced a black line playfully twisting around the steps, the walls and the ceiling (Impingement No. 56, 2010). Invited to follow it, I felt like I was chasing a cat playing with a ball of thread. With a simple move the work succeeds in re-defining a space that is often left aside by the logic of exhibitions. The same applies to the bathroom in the Artists’ Flat, where there is a comic about the Paris Commune painted on the wall, A Brief and Idealistic Account of The Paris Commune of 1871 (Sam Dargan, 2010). It is definitely a more effective reminder of our relatively recent political history than a book on a shelf by the WC. Again, the very public and the very private merge with originality and wit. In a sort of game of displacement, a work concerned with plumbing and body waste is placed on the chimney breast of the apartment’s front room (Sam Porritt, Me & You Then Everyone Else, 2010). This is clearly a work about the building, since it represents what happens deep inside it, but also the binomial public/private finds here one more way of expression, as it can be deduced from the title. Moreover, the work’s representational content is linked to the exhibition’s motto: ‘nothing is forever’.

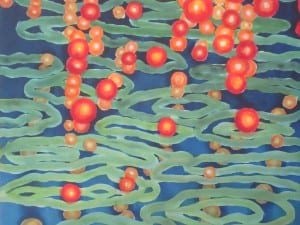

Milly Thompson has a line-drawing of a dinner party (The Dinner Party; left-field aspirational, 2010) inspired by Woody Allen’s movie Interiors (1978). There are six people sitting around a table, looking quite uncomfortable. Allen’s movie is indebted to Bergman and Antonioni for its pitiless depiction of human relationships and I guess Thompson is trying to make a similar point. One feels more at ease in other rooms, where human presence is assumed but not displayed. For example, in the first floor rooms where Ernst Caramelle has painted his intersecting colourful rectangles on the walls and around the fireplaces (Untitled, 2010). This is a work that goes beyond the canons of painting and decoration, merging traditional elements of abstract pictorial art with the architecture of the room itself, to an immersive effect.

Another smart idea for exalting the spaces of a public art gallery with a human size. The exhibition continues until 25 September. www.southlondongallery.org