On 1 March 1966, Donyale Luna, born Peggy Ann Freeman, (1945-1979) became the first woman of colour to appear on the front cover of British Vogue. The striking portrait – her face half obscured by the V-shaped fingers draped across her cheek – taken by photographer David Bailey (b. 1938), gave Luna celebrity status. Time magazine dubbed 1966 “The Luna Year”, and she appeared in magazines like Cosmopolitan and Elle alongside campaigns for Yves Saint Laurent, Mary Quant and Paco Rabanne. In 1967, Adel Rootstein manufactured a mannequin in her image. Whilst Luna’s landmark career should be celebrated, her success did not lead to a significant diversity shift within the fashion industry. It would be another eight years before Beverly Johnson (b. 1952) featured on the August 1974 edition of American Vogue, and 42 before a woman of colour shot the cover.

London-born photographer Nadine Ijewere (b. 1992) photographed singer-songwriter Dua Lipa for the January 2019 issue of British Vogue. She later shot Selena Gomez for American Vogue, April 2021, becoming the first Black woman to shoot the cover for both publications. These features followed Tyler Mitchell (b. 1995), who, in September 2018, became the first Black photographer to shoot a cover for Vogue, 126 years after its debut. Together, these photographers marked the beginning of an increase in representation behind the lens within fashion photography. Their work continues to transform the industry’s narrow parameters.

Ijewere reframes perspectives on beauty standards, exemplified in her debut monograph, Our Own Selves, published by Prestel in 2021. She also features in The New Black Vanguard, a group exhibition and book curated by Antwaun Sargent to showcase contemporary Black image-makers, along- side Namsa Leuba (b. 1982), Campbell Addy (b. 1993) and Arielle Bobb-Willis (b. 1995). The collection is now at Cali- fornia’s Museum of the African Diaspora until 5 March 2023. Alongside these creatives, Ijewere paves the way for younger generations to see themselves reflected in today’s media.

A: Beauty is a highly subjective concept. How do you draw on this in your photography? How does it relate to deconstructing stereotypes in the fashion industry?

NI: My work shows that beauty is multi-faceted. Everyone is beautiful in their own way, and these standards shouldn’t be limited to a particular ethnicity or age group. For example, my exhibition Beautiful Disruption at C/O Berlin in 2021 was designed to reflect this, rejecting these visual stereotypes and presenting a range of diverse models. I grew up look- ing at fashion magazines and thinking, “There’s no one that looks like me, my family or my friends.” I asked myself, “Why is that? Why can’t I take pictures like that?” I wanted to redress the balance through my work and to reframe misconceptions, as well as creating a space to elevate women of colour.

A: Your images pay tribute to your Nigerian and Jamaican heritage. How do you express both of these influences?

NI: In 2017, I visited Nigeria for the second time since I was five, and then I travelled to Jamaica for the first time two years later. For me, these were both important journeys. I hadn’t explored my Jamaican heritage until my late 20s. When you get older, you want to connect with your background – doing this through photography was cathartic. Now, Lagos-based photographers like Stephen Tayo (b. 1994) and Lakin Ogunbanwo (b. 1987) can capture Nigerians’ incredible fashion styles, but in the media growing up, I saw mostly negative images of Black women – Jamaican women in particular. I wanted to oppose this because it’s not true, especially with the women I spent time around. My photography is about embodying and representing my people: their greatness, positivity, sense of community and warm, welcoming energy.

A: How does photography communicate with viewers?

NI: Fashion photography didn’t reflect my reality when I was younger. I wasn’t shown women of colour in the industry, as models or photographers. I started taking pictures of my friends, and it was inspirational to celebrate our differences and subvert the standards of fashion and beauty at the time. The practice is still male-dominated, and I hope to encourage more women of colour to pick up a camera. I want them to feel that they can be photographers, make-up artists, like Ammy Drammeh, or hair stylists like Cyndia Harvey and the late LaTisha Chong. There is space for them in this industry.

A: Vivid, highly saturated colours are an important component of your work. What do these palettes signify?

NI: I love the warmth that’s achieved through these tones; it is bright and inviting, but simultaneously soft. I capture people and their energy. This correlates with the hues often seen in my work. I shoot a lot of people of colour, and these pig- ments best depict our vibrancy. It’s all about warm shades – I avoid cooler colours. You’ll often see burnt oranges, pinks and reds. I do use blue, but it’s a warmer blue. Some people might see the palettes I use in a very different way. I welcome this, and I find the myriad of interpretations illuminating.

A: Your compositions place viewers in close proximity to the model. How does this sense of intimacy function?

NI: I always want my models to shine. I don’t see them as a flat canvas. Models are more than the clothes or brand they are wearing. My work focuses on movement. There’s a dynamic, playful nature to the photography, which I think makes the images more accessible. There is a level of connection and understanding that breaks through the photographs. Women capturing women, Black women capturing Black women; it’s powerful, and it offers a new perspective.

A: You were the first Black female photographer to shoot covers for both British and American Vogue in 2019 and 2021 respectively. How did these opportunities arise?

NI: I was planning to do a shoot with Kate Phelan, a stylist and editor for British Vogue, and I was heading to a meeting with her and the Editor-in-Chief Edward Enninful. She called and told me Edward was going to ask about doing the cover and to have some references prepped. It caught me off guard. I was scrambling on the bus, trying to look through Pinterest and moodboard ideas. This was my first meeting with Edward, and we were supposed to be talking about our shoot, but when the subject of the cover came up, I just went with it. It was amazing and surreal. I was honoured to be asked to shoot a cover but, equally, I didn’t anticipate the extent of what it would mean. It was hugely significant to shoot the Vogue cover, both in terms of my career and the history of being the first woman of colour to do so in the publication’s 126-year history. This added a different level of significance.

A: After breaking these boundaries, do you feel a responsibility and pressure to keep producing new work?

NI: I am grateful for the incredible shoots I have done thus far – and to be the first person to do them on some occasions – but the pressure is immense. I had become a spokes- person for my community. This wasn’t something I set out to do when I started. I used to battle with this idea of one individual representing a whole group of people, but I have learned that it is a constant. Society likes to categorise and create labels. Now, I look to use the platform I have to open up spaces for others and break down boundaries. People also want to see what you do next. You are constantly per- forming. I am better at handling it now, but it has taken me a while to get to a space where I take pictures purely for the love of my craft. Ultimately, I remember that I don’t take pictures for others; I take them for myself. I want to take photographs because I believe in the idea, for example, a specific location, background or garment – and this is what I love.

A: Social media continues to impact how images are shared. How would you define your relationship with it?

NI: Social media was hugely influential in starting my career. I studied at London College of Fashion for a BA in Fashion Photography (2010-2013), and I worked on personal projects that I would share on my early social media platforms. From there, I started to get work. Now I have a love-hate relationship with Instagram. It was helpful, but it can make me doubt my ambition. I question whether people will like my outputs. However, social media provides a space for viewers to engage with experiments and new directions. When I re- search a shoot, sometimes I can’t find certain images because they don’t exist. Even today, there are styles of photography that haven’t been created yet, but social media helps to share new content, as the younger generation produces it.

A: In Our Own Selves, you discuss pushing for greater representation of women of colour in fashion photography. Are you seeing real step-change in the sector?

NI: It is definitely changing. What’s most important is that diversity is seen in front of the lens and behind it. Black creatives and people of colour are working in roles across the industry, as editors-in-chief, art directors, and directors of photography, but there is still more to do. We are tired of fashion imagery not reflecting society. It’s important for me to fight for representation because, for a very long time, there was not enough diversity. It is still male and white-dominated; navigating the world as a Black woman is not easy.

A: As a child, you loved fashion magazines like Vogue, but you didn’t see people who looked like you. What impact do you hope young Black women seeing themselves reflected will have on the next generation?

NI: People don’t realise there is space to tell your story, not just through photography but with art and creative direction, too. I hope that work from myself and other people like me makes these possibilities more evident to the next genera- tion. When I think of young girls seeing themselves in my images – their joy and passion – I am reminded of what my work is about, and it inspires me to keep creating in the future.

Words Megan Jones

The New Black Vanguard

MoAD, California Until 5 March

Image Credits:

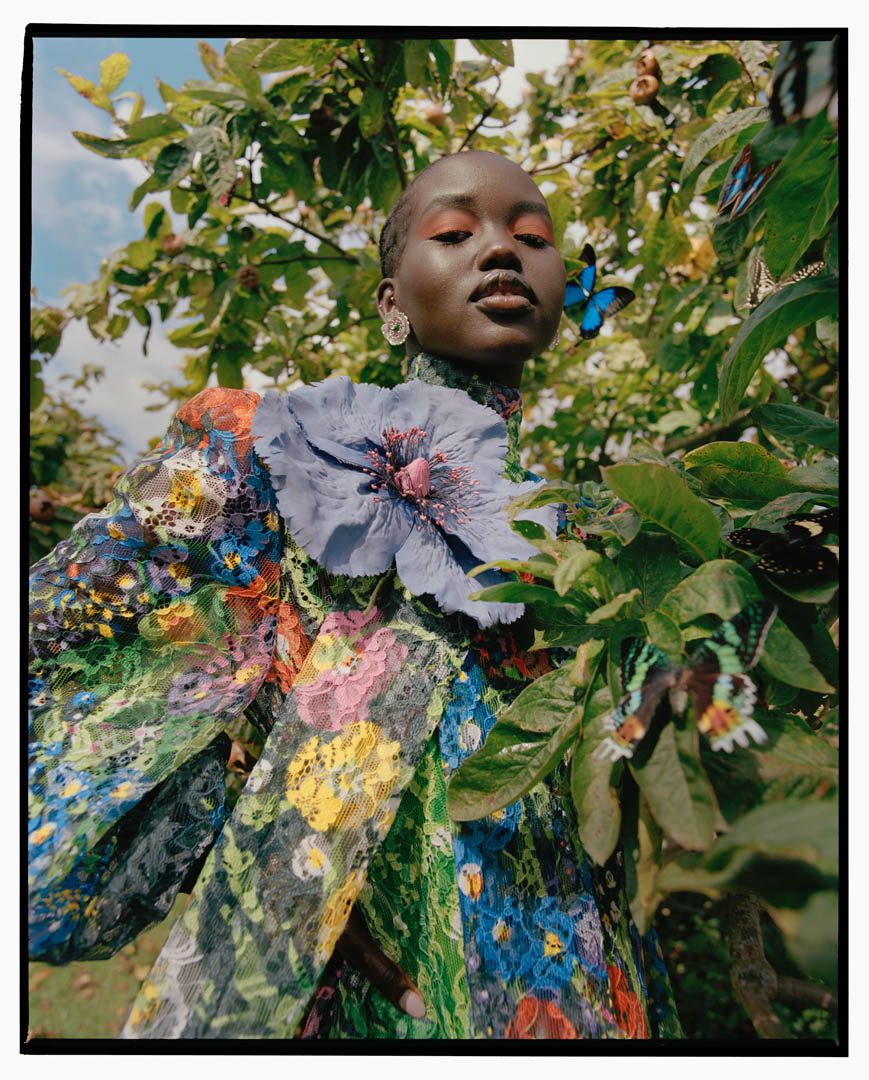

1. Nadine Ijewere, Untitled (detail) (2019). From Nina Ricci SS20 #futurestartsnow. Courtesy of the artist and Nina Ricci. Model: Scarlet Peguero. Creative Direction: Rushemy Botter & Lisi Herrebrugh. Makeup: Genesis Read. Hair: Cuchi Sanchez.

2. Nadine Ijewere, Untitled (detail) (2020). From British Vogue January 2021. Courtesy of the artist. Model: Adut Akech Styling: Poppy Kain. Set Design: Sean Thomson. Makeup: Ammy Drammeh. Hair: Sophie Jane Anderson.

3. Nadine Ijewere. From Spring Dress (detail)(2019). WSJ Magazine March 2019. Courtesy of the artist. Models: Ayobami Okekunle, Yoonmi Sun, Elibeidy Dani, Huan Zhou Styling: Coquito Cassibba. Makeup: Grace Ahn/ Hair: Junya Nakashima. Manicure: Honey.

5. Nadine Ijewere, Good Me (detail) (2019). From Rogue Fashion Book Issue 5. Courtesy of the artist. Models: Pan Haowen, Manami Kinoshita. Styling: Nathan Klein. Makeup: Celia Burton. Hair: Edward Lampley. Casting: David Chen.

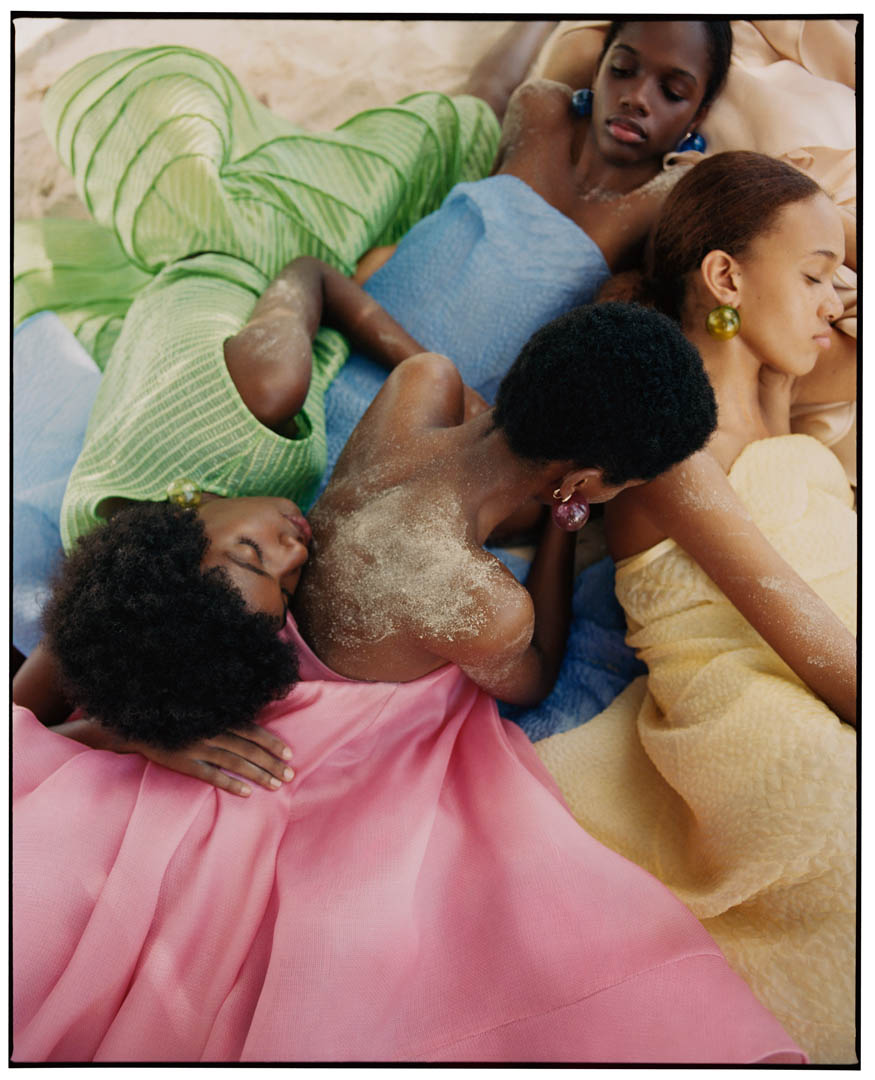

6. Nadine Ijewere, Untitled (detail) (2019). From Nina Ricci SS20 #futurestartsnow. Courtesy of the artist and Nina Ricci. Models: Scarlet Peguero, Nathalia Novas, Anamaria Figueroa, Jahika L. Gonzalez. Creative Direction: Rushemy Botter & Lisi Herrebrugh. Makeup: Genes is Read. Hair: Cuchi Sanchez.