The housewife stereotype, the conventional: the history of feminist artists of the 1970s addressed in a radical reshaping of art history at the Hamburger Kunsthalle.

“Down with religious iconography and pornographic photography, the desire for novelty, the desire of possessing women, of fantasising (about them)”. Angela Molino’s call to action in Helena Almeida: Learning to See (2005) illustrates the necessity for change in the canons of art history. A call to change that is the focus of the Viennese corporate art collection, Sammlung Verbund. Under the curatorial directorship of Gabriele Schor, the collection includes significant bodies of work by some of the key feminist avant-garde artists of the 1970s (as well as by many male artists, it should be pointed out). It is this collection that forms the basis of the current touring exhibition The Feminist Avant-Garde of the 1970s, currently on show at the Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, and curated by Schor and Merle Radtke.

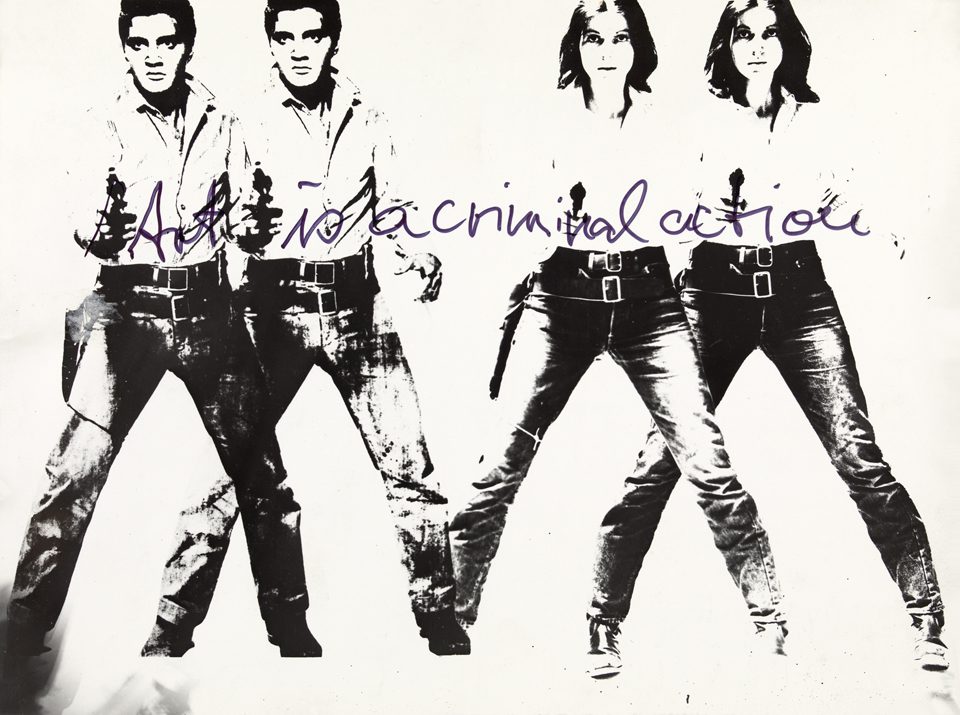

The exhibition features the work of more than 30 international women artists who collectively reshaped the way in which women and their bodies were represented. Unlike previous female group exhibitions, such as the seminal 2007 touring exhibition, WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, an international survey of the relationship between art and feminism curated by Connie Butler, Schor’s exhibition distinctly focuses on “how women artists changed the image and the representation of women in art.” Schor says that after WACK! there was a proliferation of shows popping up addressing feminist art: elles@centrepompidou (2009-2011), Rebelle: Art and Feminism (2009), and Schor’s own curated exhibition Donna (2010). WACK! was important and influential for bringing to the forefront known and unknown female artists from the 1970s onwards, and indeed it had a massive influence on the collecting strategy of the Sammlung Verbund. Butler’s intention with WACK! was crystal clear: “To make the case that feminism’s impact on art of the 1970s constitutes the most influential international art ‘movement’ of any during the post-war period.” Butler continues though, explaining that the reason the movement hasn’t achieved this recognised status is “because of the fact that it is seldom cohered, formally or critically, to a movement in the same way as Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism or even Fluxus.”

Schor, in a way, is formalising and making coherent the feminist art movement through this marrying of the term “avant-garde” with the movement. She demands the revision of the canon of art history: for the women’s avant-garde movement to be part of the collective conscious, rather than a side note. This is happening, slowly but surely, with its roots in the work of these female artists. The history of women in the art world is not just contained to female artists though – female curators face the same uphill battle: documenta, which has been running since 1955, had its first female curator in 1997 (documenta X). The Venice Biennale, which began in 1895, only had its first female curators (two women held the curatorial reins, Maria de Corral and Rosa Martinez) in 2005 – 110 years after it began.

Birgit Jürgenssen demanded this revision herself when in a letter to the DuMont publishing company (dated 1 April, 1974) she asked them to publish a miscellany on women artists: “So often the woman is an art object, rarely and reluctantly she is able to speak or show (her work) up. I, for once, would like to have the possibility to compare myself not just to my male, but also to my female colleagues.” The same year that Jürgenssen demanded this, Lynda Benglis published an advertisement in Artforum for her upcoming exhibition at Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

This is the most famous advertisement in Artforum’s history, we see a naked, oiled, sun-glass-wearing Benglis holding a large latex dildo between her thighs. This image was revolutionary for many reasons, but for many it was her facial expression that caused the most uproar: defiant, lips-parted, self-confident and clearly enjoying the moment. Roberta Smith succinctly sums this up in a New York Times article of 2009: “The sense of empowerment, entitlement, aggressiveness and forthrightness so often misunderstood to be the province of men. This more than any object, penile or otherwise, is what Lynda Benglis waved at the art world.”

To interrogate the history of women and their representation is a lengthy process, and Schor has selected the best decade for such a study. It is a decade rich in feminist political and “activist” art, some quite obviously so, such as Leslie Labowitz and Suzanne Lacy’s In Mourning and In Rage (1977). Performed on the steps of Los Angeles City Hall, it consisted of 10 women performers, nine all in black and one clad in scarlet, representing the ten Los Angeles women who had been raped and murdered by the “Hillside Strangler”. Each performer spoke to the crowd, describing a different form of violence against women using real numerical statistics. The performance was widely covered by the media and served to highlight the sensationalist attitude taken by the media and society towards not just this serial killer, but to violence against women in general. This work precedes the 1978 work by Alexis Hunter, Dialogue with a Rapist. Based on her actual experience, being accosted late at night by a man with a knife in the street, Hunter (a self-coined radical feminist) uses photography and text in this sequential series. Her telling of the experience incites fear at first, but at the end shifts the focus back to the man, with a sudden change in the situation: Man: Where do you live? / Woman: Oh…just around here somewhere… / Man: I’ll follow you home if you like / Woman: I think I’ll look after myself thanks – ‘bye! The male aggressor, the villain, becomes the protector, but Hunter very clearly and defiantly states her own abilities: “I’ll look after myself thanks”. Hunter creates the narrative through text, rather than the image, allowing her audience to formulate the visuals and by doing so placing themselves in the situation. The narrative lends itself to this method, as it is a real event and one which happens more often than it should. Lacey and Labowitz publicly staged a performance whereas Hunter created a more personal piece, but both are socio-political critiques dealing with the problem of violence against women.

The exhibition includes artists whose work is more subtle, though not overtly political or dealing with a real issue or experience (as with Labowitz and Lacy and Hunter’s), still critiques and makes visible the misogyny and stereotypes existent during the period. The work of Portuguese artist Helena Almeida has been described as “[being] neither body art, nor performance, painting, drawing or photography: that is to say, her work was affirmed as a negation of all the different artistic disciplines.” By negating these disciplines though, Molina argues that Almeida frees them from their limits and enables them to have an added dimension. With Estudo para dois espaços (1977), Almeida’s hands are pictured draped lightly through iron gates and then fencing: it is unclear as to whether she is captured, looking out or looking in on her captives. The work is a subtle critique of the time when women were simultaneously included and excluded in the art establishment. This is representative of a wider critique that runs through the work of many of the artists in this exhibition: that which Schor defines as the change between the representation of the female body from object to subject. The female body is no longer a naked, sexualized object, as depicted by the male: it has quite tangibly shifted from being passive to an active subject.

The work of Cindy Sherman, Penny Slinger and Birgit Jürgenssen makes an active, outright rejection of traditional female stereotypes and portrayals. Jürgenssen, famously, in Hausfrauen-Küchenschürze (Housewives’ Kitchen Apron) (1975) wears a kitchen stove around her neck. Dressed as a housewife, the stove covers her body, signifying her purpose as functional object. The oven door is open, a loaf of bread poking out: it is both a phallic allusion and one referencing the birth of a child. Slinger’s Wedding Invitation – 2 (Art is Just a Piece of Cake) (1973), is deft in its portrayal of herself as a wedding cake. Seated with legs akimbo, wearing a constructed traditional tiered wedding cake, with an open smile on her face and wearing a white wedding veil, the image is humorous but wickedly clever in its deconstruction of what the traditional wedding signified(s). The cake is sliced open to reveal her vagina, which has a small white flower on it: Slinger is adeptly and openly critiquing the expectation that a woman would remain a virgin until her wedding day, a day in which she would be “deflowered”. Jürgenssen and Slinger use their bodies in these staged photographs to point out the one-dimensional roles traditionally assigned to women: to produce babies and be a housewife.

More specific to the body, the female face became a natural site of contention and discourse: Francesca Woodman’s Face, Providence, Rhode Island, 1975-1976, Jürgenssen’s Ohne Titel (1979), and Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Roberta Construction Chart #1 (1975), an image of Hershman Leeson’s alter-ego Roberta Breitmore, all being key examples. Roberta Breitmore was a four- year performance project begun in 1974, with Roberta existing as a fictional person in real time in her own living quarters, which culminated in an exorcism of Roberta in 1978 (her death). The documentation of her existence is to be found in works such as this “construction chart”, where Hershman Leeson documents the literal construction of Roberta’s face through the application of make-up. Hershman Leeson is quite vividly articulating the idea that women, through the systematic daily routine of applying make-up, are constructing their own “alter-ego”. Jürgenssen does the same with Ohne Titel, a self-portrait with an eerie hand-made skeleton mask placed just inches from her face, masking all save for a glimpse of her eye and cheekbone.

Ewa Partum took this one step further with Change (1974), an investigation into the complicated relationship between women and the process of ageing. Performed in Galeria Adres, Poland, Partum had half of her face painted with heavy make-up to make her appear aged. She then sat for a portrait, the pose and facial expression mimicking Leonardo da Vinci’s portrait of one of the world’s most famous visages: the Mona Lisa. Partum, Hershmann Leeson, and Jürgenssen are each questioning what constitutes female “beauty”: is it what is underneath, the skeletal mask signifying the interior? Are women only beautiful with a mask of make-up? How do we live up to societal standards of beauty when we age? Is the female body the site of identity? These questions are further complicated by the reception of female artists in the 1970s by other female artists: Schor gives the example of Jürgenssen being reproached by feminist artists for wearing make-up and dressing fashionably, a critique that Hannah Wilke famously responded to with Marxism and Art: Beware of Fascist Feminism (1977). The social conventions of what constitutes beauty and how “beauty” is represented is still being questioned, critiqued and analysed – more openly, yes, but nonetheless still in question. Joan Riviere, in her essay of 1929 Womanliness as a Masquerade, published in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis, says: “Womanliness […] could be worn as a mask […] The reader may ask where I draw the line between genuine womanliness and the masquerade. My suggestion is […] that there is no such difference; whether radical or superficial, they are the same thing.”

The feminist movement of the 1970s, the feminist avant-garde, is becoming more and more widely researched, collected and identified. Things have changed significantly since the 1970s, and Schor says she sees a level of self-confidence in young female artists that wouldn’t have been possible without the movement’s revolution, lasting impact and legacy. Yet there is still much historical revision and research to be done to firmly entrench the feminist avant-garde movement in art history. To end with a quote from Molina, as begun: “Careful! – the artist seems to say – history is out there, in ancient tomes buried under the weight of history; in my studio the woman is no longer the equidistant point between the obscene and the beautiful.”

The Feminist Avant-Garde of the 1970s ran until 31 May. For further information, visit www.hamburger-kunsthalle.de.

Niamh Coghlan