In 1990, the January issue of Vogue launched with the black- and-white image of models Linda Evangelista, Naomi Campbell, Tatjana Patitz, Cindy Crawford and Christy Turlington. The now-iconic image, captured by German photographer Peter Lindbergh (1944-2019), rejected conventions of fashion photography. Rather than glamorous, highly stylised shots of models in stoic poses, he preferred relaxed compositions with genuine emotions and refused digital retouching.

This altered the industry’s trajectory, paving the way for candid works such as Roxanne Lowit’s (1942-2022) Christy Turlington and Kate Moss Laughing (1994) and Juergen Teller’s (b. 1964) Young Pink Kate (1998) – which depicts a young Moss rising from sleep. This new, carefree style of portraiture, however, continued to showcase only one type of model: a woman that conformed to conventional beauty standards, was largely able-bodied and predominantly white.

In September 2018, Atlanta-born Tyler Mitchell (b. 1995) became the first Black photographer to shoot a cover for Vogue, 126 years after the publication’s debut. The image of Beyoncé, crowned in an elaborate floral headpiece, symbolised the beginning of an expansion to the industry’s previously narrow lens. Antwaun Sargent, Curator and Director at Gagosian – the site of Mitchell’s latest exhibition – says he has “established himself as one of the defining photographers of his generation.” He continues to advocate for great- er representation of Black people both in front and behind the camera, joining a growing selection of young creatives dedicated to dismantling the industry’s predominately white gaze. Amongst his contemporaries are 23-year-old Yasmina Atta, who examines African culture through a surrealist lens; Jamal Nxedlana (b. 1985), exploring anti-racist activism in queer communities; and Nadine Ijewere (b. 1992), whose work makes space for diverse models. These photographers are committed to redefining our visual narrative – broadening the scope of the people, places and experiences we see represented by brands, in magazines and on our screens.

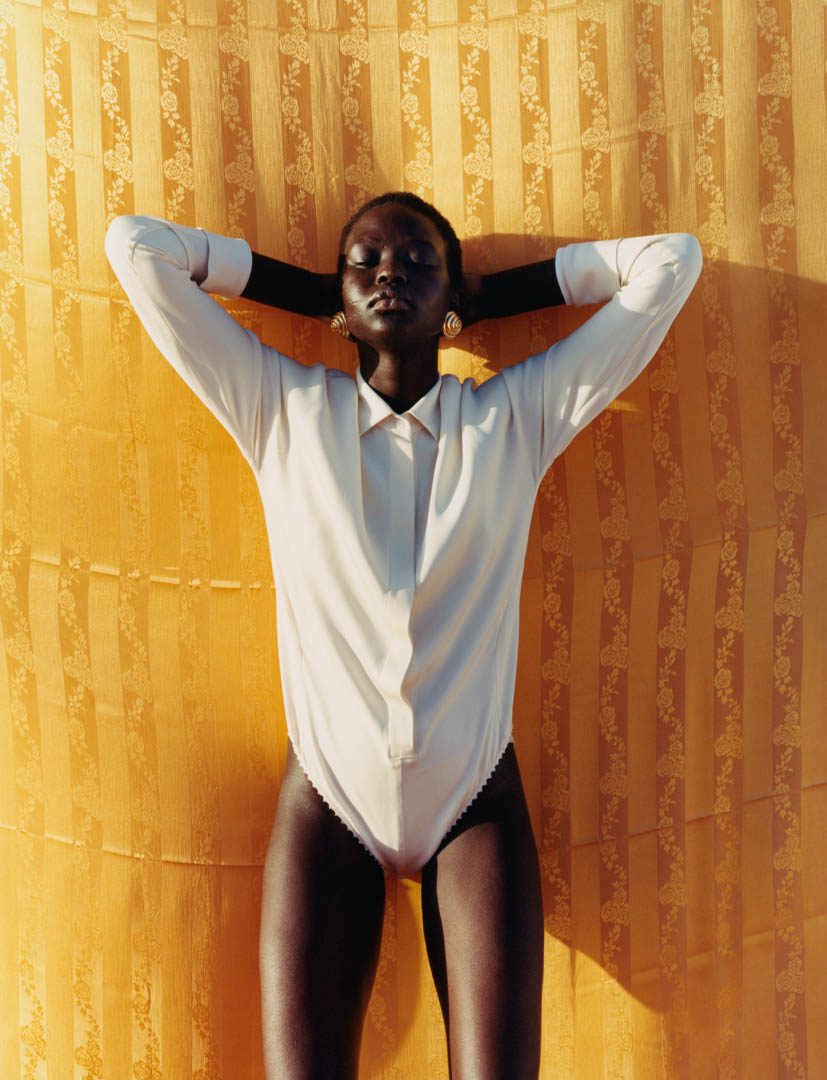

Chrysalis at Gagosian, London, is Mitchell’s first UK show. The series documents his transition from fashion photography to fine art, as well as his continued commitment to a “utopian vision of Black beauty, desire, and belonging.”

A: The title Chrysalis implies a transformational state. How do the photographs at Gagosian relate to this idea?

TM: I have done two museum shows and extensive work in the fashion space, but this is only the second show where I’ve made work specifically for a gallery. When I started putting ideas together, I thought about what it meant to make pho- tographs for display. There are a lot of beliefs around how a second show is harder than the first because the excitement is no longer there. I found myself in this transitory phase, be- tween and betwixt, caught between fashion and art. I thought Chrysalis was so fitting both for the work and myself. The images are about that psychological or emotional state. Young Black men and women are cocooning themselves, gazing at the viewer, resting or in a state or repose within the landscape. They are relaxing, meditating and interacting with the environment around them whilst also grappling with their own selves. It’s an idyllic state. That’s what the work is about.

A: This series follows the acclaimed I Can Make You Feel Good (2020), which is your first monograph. How do these works speak to – or depart from – those pictures?

TM: Both. They’re an evolution. Everything I do is somehow connected or related. Chrysalis has a different tone. There are certain signatures. Both Chrysalis and I Can Make You Feel Good are about how Black people psychologically relate to outdoor public spaces. My latest exhibition embraces more of the threatening elements of the outdoors, bringing out those question through different aesthetic, storytelling and narrative strategies. For example, mud is a new detail, and it gives the images a more eerie tone. Overall, I Can Make You Feel Good is an exploration of the positive elements of outdoors, putting forward a narrative of optimism. Chrysalis, conversely, also examines the dangers – social, political and historical – around Black folks existing in spaces in America.

A: In September 2018, you became the first Black photographer to shoot a cover for Vogue with an image of Beyoncé. How would you describe that experience?

TM: It was great. I honestly felt very honoured to be asked, and I’m proud of that assignment. It happened four years ago, so to a certain degree I feel distanced from it. I’ve been lucky enough to produce a lot of images in the fashion context since then. They’ve had a personal resonance, in which I’ve been offered a new way of understanding and looking at individuality. All the work I do is tied to fashion photography. This exhibition is connected to the commissions and brands I’ve partnered with – like Adidas, Vanity Fair, JW Anderson and AnOther Magazine. It’s all about finding these height- ened moments of beauty and contemplation in the everyday.

A: You made history at 23 – how did that feel? Did you know where to take your photography from there or how you wanted to develop? What conversations did you want to engage with as an artist following this acclaim?

TM: I don’t know if it was that calculated. I’m young, and I want to experiment. The way I work is orientated around pushing myself to a new limit, rather than growing comfortable. I’m interested in practising and learning by doing, which is how I’ve always grown new skills. I’m grateful to have been given the space to do that at a high level and on a public stage. What’s lucky about the way I relate to the industry is that the people in my circle – the community around me – understand my process and give me the space to develop in that way. That is so rare. It is a joy to have the luxury to con- sider how my current show relates to the previous one and, ultimately, how that will relate to my third. I need that space to push myself, rather than sitting in a state of complacency.

A: How would you describe the relationship between you, as the artist, and the viewer? What do you want their experience to be? How do you balance creative control?

TM: Photography is very open-ended. I’m often thinking about lots of different elements, and then I make choices. I’m not relinquishing responsibility, but in terms of what will result or what people receive from my photographs, there’s a certain amount of work participants have to do to reach their own conclusions. There are a lot of legible elements. I’m not interested in hiding parts of the narrative. I want to tell sto- ries in the most direct, efficient way possible. I enjoy making choices and allowing the viewer to try and understand those layers. Many people do, whilst others see things in them that I don’t. That’s what excites me about the medium. People try and bind photography up with the burden of fact and biography. They ask questions like: what year was this made? Who’s the person in the picture? Did you ask them to take it? Did you steal this moment? Instead, I’m trying to free the viewer from those questions and allow them to understand the layers in the picture emotionally and psychologically.

A: You believe that technology is fundamental to increasing the accessibility of photography. In what ways will this access have a powerful impact on image making?

TM: Time will tell. That’s the best answer. I’m trying to figure it out myself. I’m happy that there’s so much more access. I’m always pushing for this idea that images are, and forever will be, central, not only to fine art but to the world. Photography continues to be ignored as a practice, and I think we need to stop denying that truth and move on. It’s a battle that’s been fought and ultimately won. Artists across generations have made wonderful pictures that stand on the same level as other great works of art and other mediums. For me, it’s not even a conversation, and yet still we need to have it. Technology is democratising and broadening its availability; this will help further the change. We need to become more aware that images are central to culture. Unimpeded by genre or boundary, they have the power to alter our consciousness.

A: Do you see this movement improving diversity across the industry? How is it affecting fashion photography?

TM: It’s happening slowly. I’m happy to be part of that shift. The opening up of photography and its limits – it has already occurred. The biggest breakthrough is that everyone has a decent camera in their pocket with their phone. Every- one can make potentially powerful images, which is both a scary and exciting thought. The best will continue to float to the top – ideally, in a meritocracy. All of that will lead to an opening up of who’s behind the camera and who tells what stories. That’s incredibly important to the medium as well.

A: What were your first experiences with fashion photography? Do you recognise any aspects of these early works in either your current and future projects?

TM: About a decade ago, I was interested mainly in filming and photographing friends skateboarding. I was a skate-boarder. That has very little connection with what I do now – other than it being this joyful communal sport and that I still continue to photograph people outdoors – but my photography grew from there. I went to Havana, Cuba, in 2015, and a teacher there asked the class for pre-existing work. I presented casual portraits of friends in my New York apartment and, in many of them, I had asked my friends to wear my clothes. The teacher saw this and said, “It looks to me like you’re doing fashion photography.” I didn’t know what he meant by that at first. I found out that the images had a sense of style to them – it wasn’t that I knew what Prada or Gucci was, but it was clear that I was as interested in the clothes as I was the person. He said, “It looks like you’ve dressed them up,” and, in a way, I had. That experience opened up my understanding of how to take photos of people because I learned that what they’re wearing is as important – in terms of what it communicates – as what they’re doing, what they look like and the environment they inhabit. That’s always been a part of my work, which I still feel connected to today.

Words Megan Jones

Chrysalis, Gagosian, London Until 12 November | gagosian.com

Image Credits:

1. Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (2022). © Tyler Mitchell. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

2. Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Toni) (2019). © Tyler Mitchell. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

3. Tyler Mitchell, Strike Gold (detail) (2018). © Tyler Mitchell. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

4. Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Stilts II) (2019). © Tyler Mitchell. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

5. Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (New Royals) (2018). © Tyler Mitchell. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.