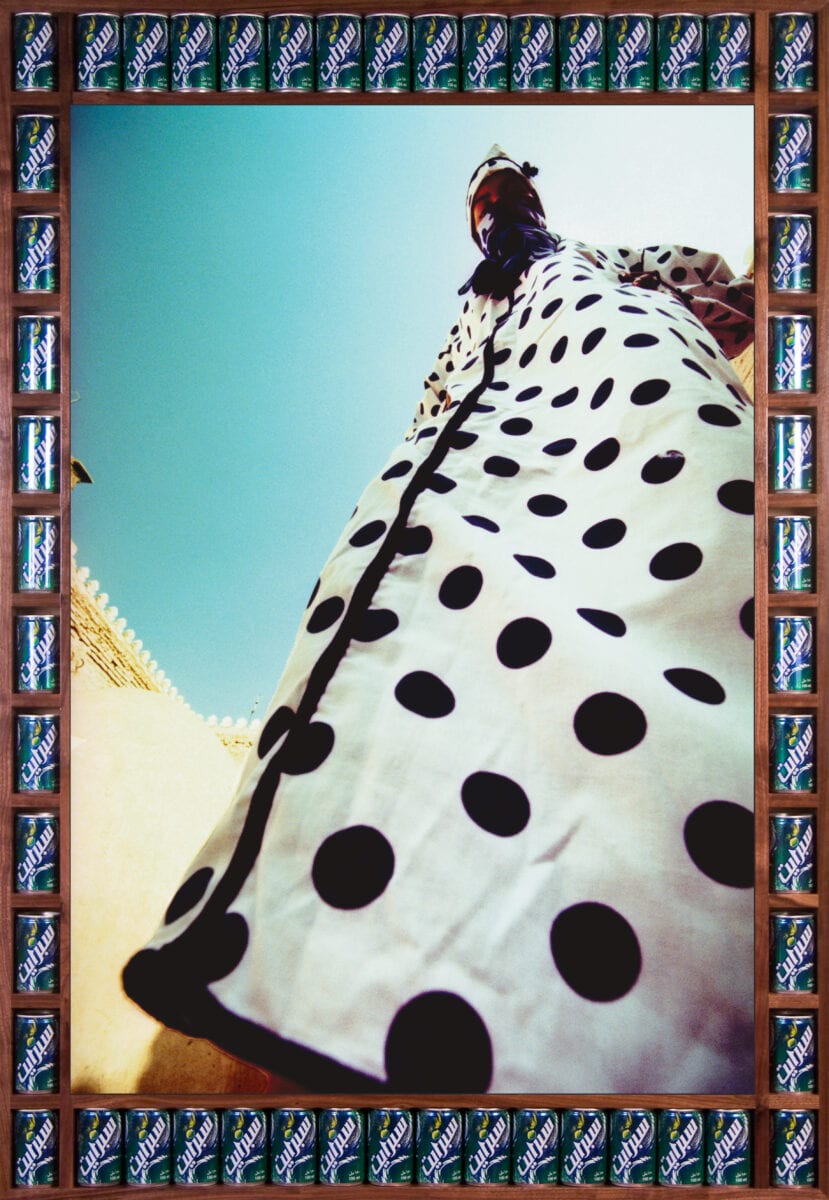

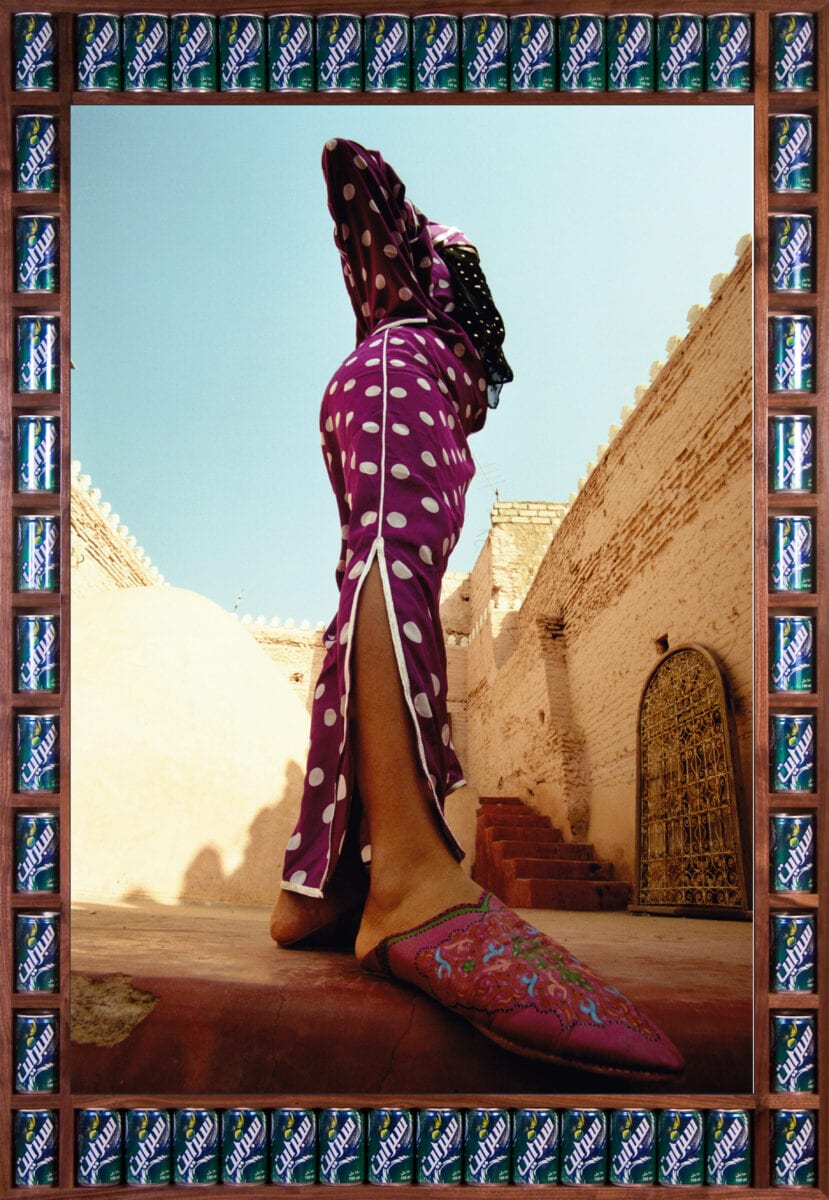

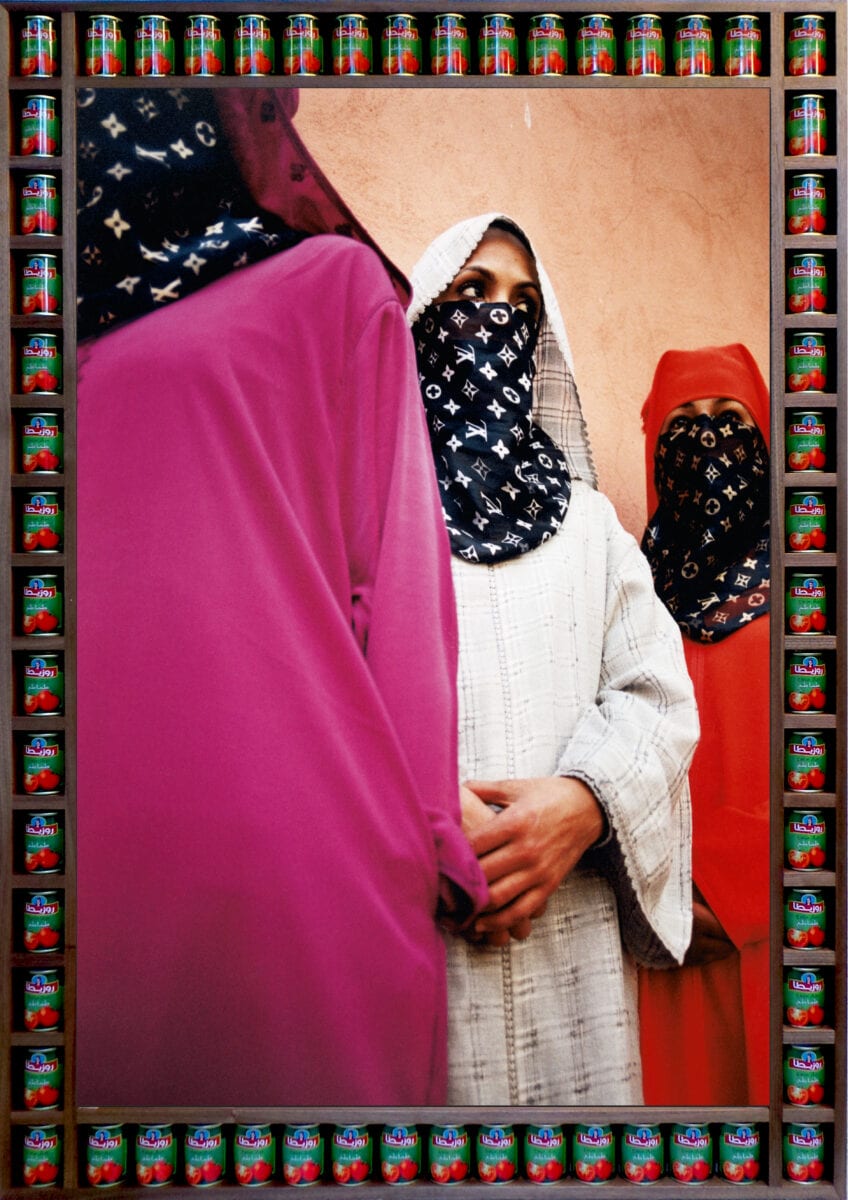

Hajjaj’s images democratise fashion labels and patterns, blending North African culture with western iconographies to explore complex identities.

Hassan Hajjaj (b. 1961) is a Moroccan-British photographer who has been named the “Andy Warhol of Marrakech.” Blend- ing the glossy aesthetic of fashion shoots with Moroccan tradition and street culture, his bold, detailed images challenge culture-specific beliefs, predominantly western perceptions of the Hijab and female disempowerment in Islam. These al- luring, multi-layered compositions fuse contemporary North African culture with familiar western iconography. They do so through appropriation, subversion and adaption, blur- ring boundaries through contrasting patterns – from stacked soup cans to Louis Vuitton prints. These eye-catching art- works reflect the artist’s neo-nomadic lifestyle and the personal relationships he has formed along the way.

Hajjaj’s work is in the collections of prestigious institutions including Guggenheim, Abu Dhabi, UAE; MAXXI National Museum, Rome; Museum of African Contemporary Art Al Maaden (MACAAL), Marrakech, Morocco; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA); Brooklyn Museum, New York; Newark Museum, New Jersey; Victoria and Albert Museum, London and The British Museum, London. He has exhibited at Somerset House, London; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; and Saatchi Gallery, London. His most recent exhibition, The Path, was a touring show commissioned by New Art Exchange, Nottingham, curated by Ekow Eshun.

A: Did you always plan to be an artist?

HH: It was totally accidental. I never really planned to be an artist. I’ve always taken photos for pleasure, but I guess the turning point was meeting Rose Issa, who had a gallery and saw something in my work. Next thing I knew, she was making me step into the art world – something I had never really dreamt of doing. It might be why I always want to welcome people who do not usually attend exhibitions or galleries.

A: You moved to Britain when you were 12 – in the 1970s – and have since lived and worked between Morocco and the UK. How do you tease out the connections and contradictions between these countries; your dual heritage?

HH: Moving to London ultimately gave me another perspective about where I came from. This has since been a driving force behind my work. I’ll always remember the feel- ing of the technicolour film I’d left behind when I arrived in London. I got there on a grey day and people were wear- ing quite dark, dull coloured clothes. It felt like a black and white movie. I come from blue skies, blue seas, colourful garments and markets. That initial contrast has since been a huge influence in my use, and understanding, of colour.

A: How do you connect inspiration from the club, hip-hop and reggae scenes of London as well as North African tradition – from the historic to the contemporary?

HH: When I look at my images, I can see the journey I’ve taken: meeting great people who have agreed to be in my work and enrich it. My first series was called Graffix from the Souk, and was a way of sharing where I came from to my London friends. I always enjoyed our exchanges of food: Caribbean, Indian, Brazilian. I experienced new forms of music and culture which broadened my horizons, and it’s interesting to see that it did not dilute, but expand, my identity. Moroccan culture is very generous and hospitable in its nature, and through my installation I want to share this inherited generosity and hospitality.

A: You move between portraiture, installation, sculpture, and performance. How would you define your images? Do you think they sit within a particular style or genre?

HH: I offer a specific kind of aesthetic and method which has been inspired by studio photographers like Seydou Keïta or Malick Sidibé – but doing it my own way. For me, it’s all in the subtlety of layering. I also find that there’s a limit to photography, so I extend the images further into videos, in which I allow playfulness and humour to take hold.

A: The images are also framed, often by found items such as canned vegetables, Sprite cans and tomato soup tins, which clash against the patterned clothing. How do these items speak to the photographs – formally, thematically and compositionally? How do you decide which items to use? Where do you source them from and is this important in terms of how they tap into your identity?

HH: The idea to use objects as frameworks came from my early work in the 1990s. I wanted my photos to have finished frames – borders which would help to “complete” them. Aesthetically, it comprises using repeated motifs like Zellige patterns – handmade mosaic tiles – and using local products in Moorish design. Sadly, I often find that lots of people see the tin cans before the image itself, but, in a way, it has made them universally accessible – it has allowed my work to be for everyone, to see something familiar as a pathway into the photograph. There are a lot of iconographies that different people can relate to in different ways. However, these frames go beyond the aesthetics and add nuances. The items I choose indicate more information about the sitter as well: what they are like, where they are form or what they do for a living.

A: You often adopt and appropriate well-known logos, from camouflage print to Louis Vuitton patterns, as well as signs and symbols from around the world that often appear in advertising and mass media. How do you draw attention to these icons to subvert eurocentric ideas? HH: I’ve always loved graphics, and I wore some of these prints when I was young (not the real brands, of course.) When you go to the Souk in Morocco there are a lot of brands. These are important, but the sellers aren’t malicious or scheming in what they sell. They don’t pretend that the clothes are the real thing and they’re not – they’re not even a copy. The sellers are just trying to make these patterns accessible – to sell ideas from brands that weren’t made for us. I carry this idea into my work by democratising logos.

A: How do you plan the colours and patterns within the images? How do you hope to draw the viewer’s eye, and to what? In an age filled with constant noise and information, how do these clashing textures feed into this, and provide exaggeration or subversion?

HH: I use clashing colours because it makes me feel something. I remember reading, in a western magazine, that there are certain colours that don’t “go” together. I disagreed. One time I was on a shoot and I felt compelled to mix brown and blue. That was the point for me where I stopped thinking and started feeling intuitively. It seems to work for me.

A: Dakka Marrakchia depicts women posing like fashion models on streets and rooftops, with designer clothing, heart-shaped sunglasses and mopeds. The images in this series often take a low angle, looking upwards at the figures. How are these works a deliberate rebuff of stereotypes of Islamic women as subjugated? Can you tell us more about the women that you shot?

HH: When I made this body of work, I took pictures of friends around me who were henna artists, dancers and neighbours. Really, the series was a reaction to a French fashion shoot I had been on. They used Morocco as a backdrop, but they didn’t incorporate any real cultural aspect of the place. It was only a pretty background. So, I decided to re-create what I had in my mind: portraying local women and showcasing their real opinions and attitudes. This really reflected the kinds of women I grew up with: strong figures. I played with fashion and accessories to highlight and subvert stereotypes, whilst keeping it inherently Moroccan. Camo was big in fashion – referencing military pants and jackets – but there were no Djellabas with this print. I want to show that, even if our clothing looks “traditional”, trends carry through to all parts of the world and are fed into all cultures and materials.

A: In My Rockstars, you turn focus to British personalities, concentrating primarily on figures such as jazz musician Kamaal Williams, demonstrating Britain as dynamically diverse. You’ve also produced many portraits of inter- national musicians and artists – including Billie Eilish, Cardi B and Madonna – bringing them into your unique aesthetic. To what extent do you feel that you disrupt the idea of hierarchy and celebrity through these portraits?

HH: My Rockstars is a long, ongoing project, highlighting our commonalities and resisting these divisive times. It started with me shooting pictures of those who I deemed to be “rock- stars” in my eyes. Eventually, this led to me photographing other well-known figures from across the world. However, this was not something I was initially looking at doing – I was really just trying to document popular culture in all its complexity and diversity. It’s very important to understand that the celebrities I have photographed are not integral to my practice, even though, of course, they are getting the most attention. This is a condition that’s reflective of the world we live in, where notoriety is valued, and that’s inherently interesting to note. Hopefully we will find more of a balance in future and less of a weighted system between those known and unknown. In the meantime, please check out all of my Rockstars – this extends to those whom I define as celebrity.

A: What, to you, is the definition of an artist? How do you see your role today? Is there something that you strive for when you embark on a new project or commission?

HH: To remain true to myself is my first priority. I believe I’m here to bring certain aspects of culture and society forward. It’s not my place to comment, but to show something in a new way. I love it when my photography creates debates. For example, I’m often referred to as the “Andy Warhol of Marrakech” in the press. This presents an intriguing question as to whether this comparison is relevant or not. Is it just easier to introduce a Moroccan artist in the western world in this way? With this framework? I don’t know, but there is a conversation to be had here. The veil was also a strong, controversial subject and I’m happy to see that it’s less so these days.

Words

Kate Simpson

@hassanhajjaj_larache

taymourgrahne.com

Lead Image: Dotted Peace, framed photography by ©Hassan Hajjaj, 2000/1421.

1: Kesh Angels, framed photography by ©Hassan Hajjaj, 2010/1431.

2: Pois Bleu, framed photography by ©Hassan Hajjaj, 2000/1421.

3: Pois Poulet, framed photography by ©Hassan Hajjaj, 2000/1421.

4: Three Women, framed photography by ©Hassan Hajjaj, 2002/1423.